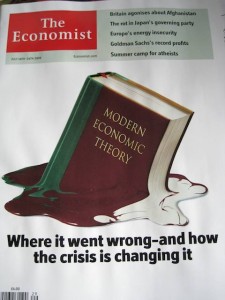

One of the most enjoyable pieces of academic work I’ve ever done was in the late 1970s when my philosopher friend Gerard de Vries of the University of Amsterdam and I did a study of the epistemological status of econometric models. (It was later published in the Dutch philosophy journal Kennis en Methode.) As an engineer I’d been intrigued by the way economists became increasingly obsessed with statistical models, and puzzled by the way in which the discipline gradually morphed into a branch of applied mathematics. This seemed to me to be yet another example of the pernicious attractiveness to social scientists of TS Kuhn’s notion of a ‘paradigm’: they convinced themselves that the way to make their subjects academically respectable was to give them an empirical core — just like physics. What none of us really appreciated was that this pathetic addiction to abstract models might have some sinister consequences.

What brought this to mind was an intriguing set of exchanges involving — of all people — Her Majesty the Queen. In November she visited the London School of Economics and, en passant asked some of the academics there why “nobody [had] noticed [before September 2008] that the credit crunch was on its way?” Which, when you come to think of it, was a bloody good question. On June 27 the British Academy, which is to the humanities what the Royal Society is to scientists, held a symposium on the subject, after which two of the eminent LSE professors who had attended wrote to the Queen, summarising the conclusions of the symposium. (Text of their letter is available here.) “Everyone seemed to be doing their own job properly on its own merit”, they wrote. “And according to standard measures of success, they were doing it well. The failure was to see how collectively this added up to a series of interconnected imbalances over which no single authority had jurisdiction. This, combined with the psychology of herding and the mantra of financial and policy gurus, lead to a dangerous recipe. Individual risks may rightly have been viewed as small, but the risk to the system as a whole was vast”.

If you’re of a suspicious turn of mind (and I am), this smacks of establishment cant. What it’s basically saying is that everyone’s to blame, which is another way of saying that nobody’s to blame, Ma’am. But in a way one could have predicted the contents of the letter by simply inspecting the list of invitees to the British Academy think-in: it’s a roll-call of establishment worthies — a Cabinet secretary here, a former Deputy-Governor of the Bank of England there, some prominent academics, a brace of retired Chief economic Advisers to the Treasury, etc.

The letter clearly irritated some economists, chief among them my friend Geoff Harcourt, one of the greatest living experts on Keynes and a life-long believer in the proposition that there’s a lot more to economics than applied mathematics. So he and his buddies set to and composed another letter to Her Majesty (text here) which seems a lot more sensible to me, mainly because it attributes some of the blame to the way in which the teaching of economics over the last two decades has been perverted by an obsession with mathematical theory and a lack of interest in what actually goes on in the real world. (Like, for example, the emergence of an unregulated ‘shadow banking’ system which came to overwhelm the normal, regulated, system.)

Geoff and his co-signatories point out that the British Academy letter

“does not consider how the preference for mathematical technique over real-world substance diverted many economists from looking at the vital whole. It fails to reflect upon the drive to specialise in narrow areas of inquiry, to the detriment of any synthetic vision. For example, it does not consider the typical omission of psychology, philosophy or economic history from the current education of economists in prestigious institutions. It mentions neither the highly questionable belief in universal ‘rationality’ nor the ‘efficient markets hypothesis’ — both widely promoted by mainstream economists. It also fails to consider how economists have also been ‘charmed by the market’ and how simplistic and reckless market solutions have been widely and vigorously promoted by many economists.

What has been scarce is a professional wisdom informed by a rich knowledge of psychology, institutional structures and historic precedents. This insufficiency has been apparent among those economists giving advice to governments, banks, businesses and policy institutes. Non-quantified warnings about the potential instability of the global financial system should have been given much more attention.

We believe that the narrow training of economists — which concentrates on mathematical techniques and the building of empirically uncontrolled formal models — has been a major reason for this failure in our profession. This defect is enhanced by the pursuit of mathematical techique for its own sake in many leading academic journals and departments of economics.”

Now enters, stage right, the formidable Richard Posner, who finds fault with both letters and calls for “a more focused criticism”. The Queen, he points out, was asking about the failure to foresee the financial collapse of last September, rather than about the health of modern economics in the large. “That failure”, he writes

“was I think due in significant part to a concept of rationality that exaggerates the amount of information that people have about the future, even experts, and to a disregard of economic factors that don’t lend themselves to expression in mathematical models, or are intractable to formal analysis. The efficient markets theory, when understood not as teaching merely that markets are hard to beat even for experts and therefore passive management of a diversified portfolio of assets is likely to outperform a strategy of picking underpriced stocks or other securities to buy and overpriced ones to sell, but as demonstrating that asset prices are always an adequate gauge of value — that there are not asset “bubbles” — blinded most economists to the housing bubble of the early 2000s and the stock market bubble that expanded with it. In modeling the business cycle, economists not only ignored, because difficult to accommodate in their mathematical models, vital institutional detail (such as the rise of the ‘shadow banking industry,’ which is what mainly collapsed last September) — often indeed ignoring money itself, on the ground that it doesn’t really affect the ‘real’ (that is, the nonfinancial) economy. They also ignored key concepts in Keynes’s analysis of the business cycle, such as hoarding and uncertainty and business confidence (‘animal spirits’) and worker resistance to nominal (as distinct from real) wage reductions in depressions. Lessons of economic history were ignored, too, leading to a belief that there would never be another depression, let alone a collapse of the banking industry. Even when the collapse occurred, in September, many macroeconomists denied that it would lead to anything worse than a mild recession; the measures that the government has taken to recover from what has turned into a depression owe little to post-Keynesian economic thinking; and the economists cannot agree on what further, if anything, should be done, and which of the government’s recovery measures has worked or will work.”

The truth of the matter is that large chunks of the analytical apparatus of modern economics has been shown to be a house of theoretical cards. But given the profession’s huge investment in said cardboard structures, it’s probably incapable of admitting its colossal mistake. Time for a Kuhnian revolution?