It’s hard to keep a bad idea down. Now it’s James Fallows’s turn to fantasise still that micropayments are the solution to online journalism’s revenue deficit.

In principle, some form of ‘micropayments’–tiny royalties for each online item – will be part of the eventual solution for financing online news. The problem is that most existing systems are too big a nuisance. In a world where people willingly pay several dollars per day for cable or satellite TV programming, you’d think that a newspaper article would be worth at least a few cents. But in practice, anything that complicates or delays the act of reading a Web page or clicking a link probably sends an online reader someplace else. It’s not the five cents that stops you; it’s having to decide over and over again to spend the next five cents. It might be the same with TV if you had to authorize a payment each time you switched to The Daily Show.

A sustainable payment system for online news has to make the process as effortless – but still as controllable – as the EZ-pass system for highway tollbooths. Or, for a more modern reference, as the SkypeOut payment system on Skype. With EZ-pass, you decide ahead of time that you’re willing to pay for tolls, so you’re spared the hassle at the booth. With SkypeOut, you decide ahead of time to spend $25 or $50 on Skype’s pennies-per-minute calls to landline phones, and you don’t have to worry about the details for each call.

It’s pure fantasy, this, as Clay Shirky pointed out ages ago:

Because small payment systems are always discussed in conversations by and for publishers, readers are assigned no independent role. In every micropayments fantasy, there is a sentence or section asserting that what the publishers want will be just fine with us, and, critically, that we will be possessed of no desires of our own that would interfere with that fantasy.

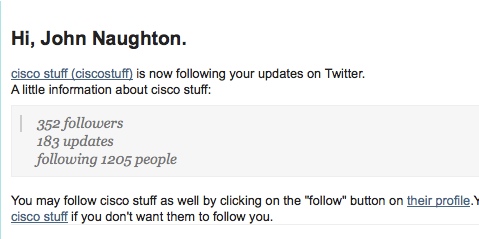

Meanwhile, back in the real world, the media business is being turned upside down by our new freedoms and our new roles. We’re not just readers anymore, or listeners or viewers. We’re not customers and we’re certainly not consumers. We’re users. We don’t consume content, we use it, and mostly what we use it for is to support our conversations with one another, because we’re media outlets now too. When I am talking about some event that just happened, whether it’s an earthquake or a basketball game, whether the conversation is in email or Facebook or Twitter, I want to link to what I’m talking about, and I want my friends to be able to read it easily, and to share it with their friends.

This is superdistribution — content moving from friend to friend through the social network, far from the original source of the story. Superdistribution, despite its unweildy name, matters to users. It matters a lot. It matters so much, in fact, that we will routinely prefer a shareable amateur source to a professional source that requires us to keep the content a secret on pain of lawsuit. (Wikipedia’s historical advantage over Britannica in one sentence.)