… As the Tesco slogan goes. Still, I don’t think that £250 million accounting ‘error’ will be regarded as a little. What the hoohah obscures, however, is what Tesco’s poor trading performance tells us about the so-called economic recovery. Tesco is in trouble because people are increasingly turning to the cut-price supermarkets (mainly Lidl and Aldi). Waitrose, meanwhile, is booming. Which, being translated, means that poorer people in Britain are feeling increasingly squeezed, while the upper middle classes who are Waitrose’s staple customers (just look at the car park the next time you visit one of their stores) are doing just fine. Some ‘recovery’.

Category Archives: Beyond belief

The Federal United Kingdom

Timothy Garton-Ash has been writing in today’s Guardian about the need for a Federal Kingdom of Britain — FKB. “Incidentally”, he concludes,

I Googled to check whether “FKB” is already taken. It is: by the Flying Karamazov Brothers, a theatrical troupe of comic jugglers, sometimes attired in kilts. Seems like a pretty good description of Britain’s party leaders right now.

The Umbrella Man

The Umbrella Man from The New York Times – Video on Vimeo.

Whenever I hear someone outline a beautifully-constructed conspiracy theory I think of Errol Morris’s video.

So did they really go to the moon in 1969?

This is 13 minutes long, but worth every second. In it film-maker S.G. Collins argues that in 1969, it was easier to send people to the Moon than to fake the landing in a studio. Technologically speaking, he says, it was impossible to shoot that video anywhere other than the surface of the Moon. A lovely piece of debunkery, filmed with the assurance of an Errol Morris.

Two antique institutions collaborate

Pot calls kettle black

Our out-of-control police forces

I hold no brief for Cliff Richard, but the behaviour of Thames Valley and Yorkshire Police forces in relation to him has been outrageous. Geoffrey Robertson QC has a terrific article about it in today’s Independent.

Last year, apparently, a complaint was made to police that the singer had indecently assaulted a youth in Sheffield a quarter of a century ago. The police had a duty to investigate, seek any corroborating evidence, and then – and only if they had reasonable grounds to suspect him of committing an offence – to give him the opportunity to refute those suspicions before a decision to charge is made.

But here, police subverted due process by waiting until Richard had left for vacation, and then orchestrating massive publicity for the raid on his house, before making any request for interview and before any question could arise of arresting or charging him.

Police initially denied “leaking” the raid, but South Yorkshire Police finally confirmed yesterday afternoon that they had been “working with a media outlet” – presumably the BBC – about the investigation. They also claimed “a number of people” had come forward with more information after seeing coverage of the operation – which leads one to suspect that this was the improper purpose behind leaking the operation in the first place. This alone calls for an independent inquiry.

The BBC and others were present when the five police cars arrived at Richard’s home, and helicopters were already clattering overhead. Police codes require that “searches must be conducted with due consideration for the property and privacy of the occupier and with no more disturbance than necessary” – here, the media were tipped off well ahead of time, and a smug officer read to the cameras a prepared press statement while the search was going on.

Among other things, if it’s true that the BBC was involved in this then the Corporation has serious questions to answer about its complicity in this. What would make it doubly ironic would be the fact that this is the same BBC that for decades provided cover and opportunities for the biggest sexual predator in recent history, Jimmy Saville.

So, first question: was the BBC complicit in this?

Second question: who was the magistrate who allowed this to proceed? “Why was a search warrant granted?” asks Robertson.

The law (the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act) requires police to satisfy a justice of the peace not only that there are reasonable grounds for believing an offence has been committed (if so, why had he not already been arrested?), but that there is material on the premises both relevant and of substantial value (to prove an indecent assault 25 years ago?).

Moreover, the warrant should only be issued if it is “not practicable to communicate” with the owner of the premises – and it would be a very dumb police force indeed that could find no way of contacting Cliff Richard. The police Codes exude concern that powers of search “be used fairly, responsibly, with respect for occupiers of premises being searched” – this search was conducted without any fairness or respect at all, other than for the media who were given every opportunity to film the bags of “evidence” being taken away.

This whole thing is a scandal. But because the popular press — and maybe the BBC — were in on it, nothing will happen.

Later A statement from South Yorkshire police:

The facts are as follows:

The force was contacted some weeks ago by a BBC reporter who made it clear he knew of the existence of an investigation. It was clear he in a position to publish it.

The force was reluctant to cooperate but felt that to do otherwise would risk losing any potential evidence, so in the interests of the investigation it was agreed that the reporter would be notified of the date of the house search in return for delaying publication of any of the facts.

Contrary to media reports, this decision was not taken in order to maximise publicity, it was taken to preserve any potential evidence.

South Yorkshire Police considers it disappointing that the BBC was slow to acknowledge that the force was not the source of the leak.

A letter of complaint has been sent to the Director General of the BBC making it clear that the broadcasters appears to have contravened it’s editorial guidelines.

So phone hacking was just a scandal, not a crisis

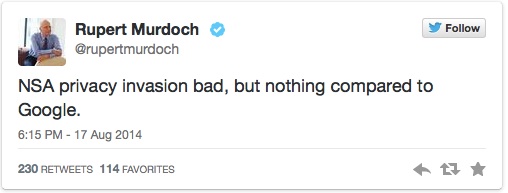

Regular readers will know how useful I find David Runciman’s distinction between scandals and crises. (Scandals happen all the time, cause a lot of fuss and result in no fundamental change. Crises do trigger substantive change.) This piece by Michael Wolff, a Murdoch biographer and general-purpose media watcher, in which he reflects on the outcome of the London trial of some Murdoch lieutenants, confirms my gloomy conjecture: that the phone-hacking business was just a scandal.

The campaign’s most potent scare symbol was the disgraced Brooks, and a story line that had her using her paper and closeness to the Murdoch family to achieve vast influence in the British government. But Brooks now emerges from the nine-month trial as something more like a martyr, herself the victim of a merciless press, ever hounded by political enemies. (With special spite, her husband, who was also acquitted, was put on trial with her for hiding computers — containing, instead of evidence, his porn collection.)

But there was a conviction — one that quite nicely serves Murdoch’s purposes. Andy Coulson, former editor of Murdoch’s weekly scandal sheet, News of the World — which closed in the wake of the hacking revelations — was the one person convicted of phone hacking in the trial. Coulson had gone on to become Prime Minister David Cameron’s press secretary. Murdoch can now maintain what he has always maintained: It was disloyal midlevel lieutenants who hacked, not anyone close to him. What’s more, Coulson becomes Cameron’s problem for hiring a now-convicted felon. Murdoch has long felt it was a wishy-washy Cameron who let the hacking investigation grow and vowed his revenge. Now he has it.

The 83-year-old Murdoch’s difficulties in London aren’t quite finished. There are ongoing hearings at which he is scheduled to testify and continuing regulatory threats against his businesses. But now the `prima facie case is gone. In a sense, it is a reset. It’s back to lots of people hating Murdoch and lots of people eager to be in his favor and do his bidding.

Nothing changes. There will be no substantive change in the way the British tabloid media operate. So it was a scandal, not a crisis.

As Peter Wilby puts it in the New Statesman:

As for hoping that newspapers will repent of their sins and now accept the royal charter that followed the Leveson inquiry, forget it. “Great day for red tops”, proclaimed the Sun, celebrating Brooks’s acquittal and treating Coulson’s conviction as a mere sideshow (a “rogue editor”, perhaps). “The Guardian, the BBC and Independent will be in mourning today,” wrote its associate editor Trevor Kavanagh. “Sanctimonious actors like Hugh Grant and Steve Coogan will be deliciously Hacked Off. We have . . . taken a tentative step back towards a genuinely free press.” Murdoch’s Times judged that Brooks’s acquittal “shows that a rush to implement a draconian regime to curb a free press was a disaster”. The Daily Mail had a leader on “the futility of Leveson”.

As the press is well aware, public outrage over hacking has long passed its peak. People don’t like the tabloids and they don’t like politicians getting too close to them. They want – or say they want – stricter controls on newspapers. But in the pollsters’ jargon, the issue has “low salience”. To most, the subject just isn’t important enough to change either their vote or their buying and surfing habits in the news market. The press can continue on its merry way.

Yep. But it ought still to be a crisis for the Prime Minister, who cheerfully employed Coulson as his spinmeister despite being explicitly warned about his background. But my hunch is that Cameron is already in such deep trouble (much of it of his own making — see his fatuous campaign to prevent Jean-Claude Juncker becoming EC President) that the Coulson debacle comes relatively low down in the list.

Neoliberalism’s revolving door

Well, guess what? The former Head of the NSA has found a lucrative retirement deal.

As the four-star general in charge of U.S. digital defenses, Keith Alexander warned repeatedly that the financial industry was among the likely targets of a major attack. Now he’s selling the message directly to the banks.

Joining a crowded field of cyber-consultants, the former National Security Agency chief is pitching his services for as much as $1 million a month. The audience is receptive: Under pressure from regulators, lawmakers and their customers, financial firms are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into barriers against digital assaults.

Alexander, who retired in March from his dual role as head of the NSA and the U.S. Cyber Command, has since met with the largest banking trade groups, stressing the threat from state-sponsored attacks bent on data destruction as well as hackers interested in stealing information or money.

“It would be devastating if one of our major banks was hit, because they’re so interconnected,” Alexander said in an interview.

Nice work if you can get it. First of all you use your position in the state bureaucracy to scare the shit out of banks. Then you pitch your services as the guy who can help them escape Nemesis.

The Internet of Things: it’s a really big deal. Oh yeah?

This morning’s Observer column. From the headline I’m not convinced that the sub-editors spotted the irony.

Like I said, everybody who is anybody in the tech business is very turned on by the IoT. It’s going to make lots of money – oh, and it’ll change the world, too. Of course there are some boring old creeps who keep raining on the parade. Spoilsports, I call them. There are, for example, the “security” experts who think that the IoT opens up horrendous vulnerabilities for our networked society. Hackers in Azerbaijan could get control of our “smart” electricity meters and shut down the whole of East Anglia with the click of a mouse. Pshaw! As if the folks in Azerbaijan even knew there was such a place as East Anglia. Or some guy in Anonymous could remotely jam the accelerator in your car so that you drive into your garage at 130mph even when you have your foot firmly on the brake. As if!

That’s why it’s *sooo* annoying when the media publicise scare stories about security lapses involving connected gadgets. I mean to say, how could TRENDnet have known that its “secure” security webcams weren’t really secure at all? It’s not its fault that a hacker broke into the SecurView camera software and told other people how to do it. The result, according to the US Federal Trade Commission, was that “hackers posted links to the live feeds of nearly 700 of the cameras. The feeds displayed babies asleep in their cribs, young children playing and adults going about their daily lives”.

This is *so* unfair. Poor old TRENDnet makes security *cameras*. Why should it know anything about internet security?