The New Yorker reveals what Steve Jobs discovered when he met St Peter.

Category Archives: Asides

The grand piano is gone

Nice New Yorker piece by Nicholson Baker on his first thoughts on hitting the Apple home page and finding that lovely B&W picture of Steve Jobs.

I was stricken. Everyone who cares about music and art and movies and heroic comebacks and rich rewards and being able to carry several kinds of infinity around in your shirt pocket is taken aback by this sudden huge vacuuming-out of a titanic presence from our lives. We’ve lost our techno-impresario and digital dream granter. Vladimir Nabokov once wrote, in a letter, that when he’d finished a novel he felt like a house after the movers had carried out the grand piano. That’s what it feels like to lose this world-historical personage. The grand piano is gone.

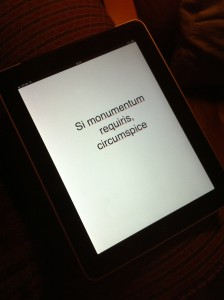

Epitaph for Steve

Myles better

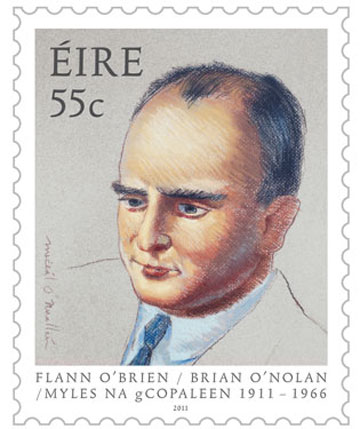

Yesterday was the centenary of the birth of Flann O’Brien, aka Brian O’Nolan, aka the author of the great post-modern novel, At Swim Two Birds, and (as Myles na gCopaleen) of the Cruskeen Lawn column in the Irish Times. To my gratified astonishment, Official Ireland, having done its best over the years of his life to belittle and ignore him, finally did the decent thing and put him on a commemorative stamp. And, in a very nice touch, the drawing of him was done by his brother, Michael.

I write with feeling on this matter. During my childhood in the 1950s, O’Brien wrote an astonishingly anarchic column for the Irish Times, then the eccentric house-organ of the Protestant ascendancy, edited by a gifted oddball named R.M. Smyllie, who had earned the undying hostility of the Catholic hierarchy because (a) he edited a Protestant newspaper, and (b) had strongly opposed General Franco, the Fascist dictator beloved of all Irish bishops. Since I grew up in a fervently Catholic household, the Irish Times was regarded as the spawn of the devil, and a copy of the paper never crossed the threshold. (Our newspaper fare was the Irish Press, the organ of Fianna Fail and the de Valera family, and the Irish Catholic, a devotional publication of stupefying piety.) But every so often I would pick up a snatch of conversation about this guy Myles na gCopaleen — literally “Myles of the Little Horses” — and wonder what the fuss was about. I determined that, one day, I would find out.

Eventually, when I was sixteen I saved up enough money to go to Dublin for a few days (staying with a relative, who lived in Ballsbridge and was deemed sufficiently strict to be able to keep an eye on me). On the first morning she inquired brightly whether I had plans for the day, and beamed approvingly when I told her that I was hoping to visit the National Library, then next to Leinster House in Kildare Street. So I took the bus down to Stephen’s Green and made my way to the Library, past a glowering custodian, lurking like the basilisk in his cave. Once inside, I discovered that I had lowered the average age of the readers by at least four decades. Undeterred, I requested back numbers of the Irish Times, which arrived, as I recall, in huge bound volumes, and commenced to read my way through the Cruskeen Lawn columns.

Coming to Myles for the first time, I found him intoxicatingly funny, which is how I came unstuck. One column in particular (I think it was one where he had put the image of a finger pointing at the Leading Article which ran alongside, the argument of which he then proceeded to ridicule) was so hilarious that I was racked by hysterical laughter. And then I suddenly noticed other readers looking disapprovingly at me, and the duty librarian over by the door talking grimly to the custodian and pointing at me. He advanced menacingly and said “We don’t want your sort here, sonny. This is a serious place. Out with yer!”. Or words to that effect.

I’ve loved Flann O’Brien’s work ever since that day. His newspaper did him proud on his centenary, with a story about the new stamp, a reprint of one of his nicest columns (in which he discusses the importance of the word “supposed” in Irish daily life) and some letters from readers drawing learned attention to his various exploits.

‘Frictionless sharing’ and Zuckerberg’s law

A few days ago I blogged about the implications of Facebook’s latest intrusions into the lives of its users. The more I looked at the idea of “frictionless sharing” the more outrageous it seems. So it was refreshing to come on this succinct dissection of the initiative by Jeff Sonderman which makes the point more cogently than I did.

Facebook spent years making it easier for us to share by building its network and placing “Like” buttons across the Web. Its latest idea goes much further, turning sharing into a thoughtless process in which everything we read, watch or listen to is shared with our friends automatically.

Encouraging sharing is great. Making sharing easier is even better. But this is much more than that. What Facebook has done is change the definition of “sharing.” It’s the difference between telling a friend about something that happened to you today and opening your entire diary.

Yep. Jeff points out that a number of news organisations (including the Guardian group, for which I write) are careering headlong down this path by ‘partnering’ with Facebook in its latest wheeze. Which brings to mind Winston Churchill’s wonderful definition of appeasement as “being nice to a crocodile in the hope that he will eat you last”.

Jeff goes on to list a number of reasons why this idea of frictionless sharing is not only fatuous, but also cynically manipulative, in that it benefits only Facebook while purporting to be useful to its eager sharecroppers.

The fact that people choose to keep most things private places significance on what they choose to share. If everything is shared automatically, nothing has significance.

If a woman reads a Yahoo News story about breast cancer and that fact is automatically noted in her Facebook activity, what are her friends to make of that? Does she have cancer? Does she have a friend with cancer? Perhaps a colleague was quoted in the article. Maybe she accidentally clicked on the wrong link.

Facebook is presenting this information with no context. In the absence of context, people make assumptions.

Can anyone in the new Facebook world read about personal health, relationship advice, personal finance or gay rights without their acquaintances speculating why? In other cases readers could be embarrassed by clicking on a Kim Kardashian photo gallery, a list of crude jokes, or anything else that some people may find distasteful.

News organizations that employ the Facebook activity feed may end up hurting themselves by making readers stop and think, “Do I really want to read this, knowing my friends will see that I did?”

Finally, Jeff asks news organisations pondering whether to jump aboard this bandwagon to ask themselves a question:

Why exactly are you doing this — for your benefit, or for the readers? Pumping Facebook full of links to your site so you can benefit from a bump in referral traffic seems good, but you risk alienating users and eroding their trust. The last thing a news organization wants is for people to think twice before they click.

Right on. Great post.

Counting one’s blessings

Today marks a pivot in my life. Yesterday I retired from the Open University, after a long and productive career there. Today I become Vice-President of Wolfson College, where I’ve been a Fellow for many years and now become part of The Management (as it were).

The worst thing about leaving an institution, I discovered, is having to clear out one’s office. I’ve spent the last week shredding a mountain of stuff — the accumulated paperwork of a 40-year academic career. (So much for the paperless office. Abi Sellen and Richard Harper were right.) It’s said that if you fall from a high cliff, your life flashes before your eyes before you hit the ground. Well, much the same thing happens when you shred the documentary evidence of a long time in an organisation — all those committee papers, project reports, task-force agendas, visits and visitors, background for research papers, letters and memoranda from The Management, and so on.

One thing that struck me as I shredded was how much energy I had expended on so many different things; many of them fizzled out, as you’d expect, but a few of them yielded real benefits. With my colleague Nigel Cross, for example, I changed the way the university approached the teaching of technology, for example, from an approach that focussed mainly on machinery and the environment, to one that was centred on issues and values as well on technical subjects. With Jake Chapman and others I persuaded the university to embrace the PC revolution and to require our students to have access to a PC for many courses; with Martin Weller I launched the institution into teaching online: our first course attracted 12,000 students in its first year, and the OU now has upwards of a quarter of a million students online; and with Tony Hirst, Ray Corrigan, Andy Lane, Jeff Johnson and others launched the OU’s Relevant Knowledge Programme of short, online courses on fast-moving technological subjects.

What also struck me as I looked back was how lucky I have been. I’m a baby-boomer, born in 1946, and what looking back over the record of references and job applications and further particulars and promotions brought home to me is the extent to which I belong to a truly blessed generation. When I graduated (with a First) in 1968 I had about thirty job offers (as an experiment, I had gone to all the ‘milk-round’ interviews then run by large corporations). All of my engineering classmates in 1968 got ‘professional’ jobs, and some went on to have very successful careers in large companies. One of my sons is now the same age as I was when I got that lectureship and he tells me that of his cohort of friends and contemporaries, only he and one of his friends have what one might describe as meaningful work. When I got my university lectureship the first thing I did was to go out and buy a house in Cambridge. None of my son’s contemporaries has been able to buy a house, and for some it looks like being an unattainable dream. And nobody on a junior lecturer’s salary could nowadays afford to buy even a simple terraced house in Cambridge. I’ve had a secure, tenured job doing interesting work for four decades, something that already seems implausible in the modern economy. And, to cap it all, I get to retire on a decent pension, linked to my final salary. If that isn’t luck, then I don’t know what is.

All of which makes it ever more frustrating to see how my generation and the ones immediately succeeding it have comprehensively screwed up the prospects for my children and grandchildren.

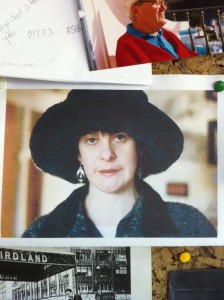

As I shredded, most of the time memories whizzed by in an interesting but untroubling blur. But then I came on a document that brought me to a shuddering halt. It was the minutes of the first committee meeting at which I came face to face with Sue, the woman who transformed my life. She was then a rising star in the University Administration, a talented, sassy, ambitious girl who was clearly destined for greater things. And as I read this anodyne record of discussions held and decisions reached I was transported back to the moment in 1986 when I sat in that Committee Room stunned by her beauty and easy grace and wondered if such creatures ever talked to mere academics. As it turned out, she did. I fell for her — hook, line and sinker — and to my astonishment she fell for me. We had twelve blissful years together, and two lovely children, before fate (as PG Wodehouse would say) slipped the lead into the boxing glove. She died from cancer nine years ago. Meeting her was the most wonderful unexpected benefit of working at the OU, and if I had got nothing else out of my career, that would have been enough to justify it.

As I shredded, most of the time memories whizzed by in an interesting but untroubling blur. But then I came on a document that brought me to a shuddering halt. It was the minutes of the first committee meeting at which I came face to face with Sue, the woman who transformed my life. She was then a rising star in the University Administration, a talented, sassy, ambitious girl who was clearly destined for greater things. And as I read this anodyne record of discussions held and decisions reached I was transported back to the moment in 1986 when I sat in that Committee Room stunned by her beauty and easy grace and wondered if such creatures ever talked to mere academics. As it turned out, she did. I fell for her — hook, line and sinker — and to my astonishment she fell for me. We had twelve blissful years together, and two lovely children, before fate (as PG Wodehouse would say) slipped the lead into the boxing glove. She died from cancer nine years ago. Meeting her was the most wonderful unexpected benefit of working at the OU, and if I had got nothing else out of my career, that would have been enough to justify it.

I’m the last cohort of employees to whom compulsory retirement age applies. From today, employers will have to make a case for making people stop at the statutory retirement age. I could have made a case to stay on, but decided against it: I had too many other things that I wanted to do. As a father of two children of university age, the idea of having a useful lump sum was attractive. And to have stayed on might also have blighted the prospects of younger colleagues, or — in a time of budget cuts — necessitated staffing reductions elsewhere.

Besides, there’s something absurd about the idea of ‘retirement’ for academics. Most of them continue to do what they do, regardless of whether they have an institutional perch or not. In my case, I’m simply moving to another corner of academia, but even if I weren’t, an observer would be hard put to notice any difference in my daily routine. I’ll still be blogging, for example. My Observer column goes on. I have a new book

Besides, there’s something absurd about the idea of ‘retirement’ for academics. Most of them continue to do what they do, regardless of whether they have an institutional perch or not. In my case, I’m simply moving to another corner of academia, but even if I weren’t, an observer would be hard put to notice any difference in my daily routine. I’ll still be blogging, for example. My Observer column goes on. I have a new book coming out in January, and am already incubating its successor. And a courier has just delivered Steven Pinker’s whopping new book

, which I’ll have to read because the Observer wants me to do an email debate with him.

In other words: business as usual.

Quote of the day

Politics is the art of making the inevitable seem like rational choice. Protest is the art of making the rational seem inevitable.

P***words

My Observer column about passwords has prompted some witty conversations and emails. Many of the latter pointed to this lovely xkcd cartoon. The punch line:

“Through 20 years of effort, we’ve successfully trained everyone to use passwords that are hard for humans to remember, but easy for computers to guess”.

Amen.

Cultural norms

You see, it’s like this…

Vint Cerf explains something to Nigel Shadbolt, High Table, Balliol, September 22, 2011.