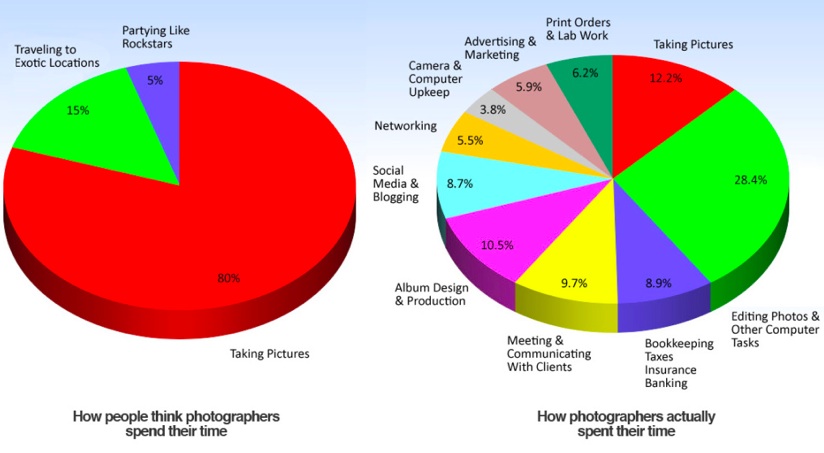

(…as compared with how people think they spend it.)

Category Archives: Asides

The USB Typewriter

This is the kind of stuff that makes my day — and makes normal people wonder what geeks are smoking.

Lovely, lovely idea. Leading edge uselessness I call it. And that’s a compliment: it’s about doing ingenious things just for fun. You can get the kit from here. Now, where did I put that old Olivetti portable?

Thanks to Brian for the link.

Language and social change

At dinner last night someone mentioned that a local village had changed the name of its village hall to “the People’s Hall”, and it suddenly made me think about how some words lose their resonance as society changes. “The People’s Hall” has a whiff of Marxist — or at any rate socialist — ideology. Likewise, nobody talks about “workers” (as in, say, the Workers’ Educational Association) any more. Come to think of it, when was the last time you heard anyone use the term “socialism” with approval? Or “progressive”? And then it just so happened that the next item on my iPod playlist was that wonderful satirical song by the Strawbs — Part of the Union.

LATER: I remembered something Ross McKibben once wrote about Margaret Thatcher:

Her fundamental aim was to destroy the Labour Party and ‘socialism’, not to transform the British economy. If the destruction of socialism also transformed the economy, well and good, but that was for her a second-order achievement. Socialism was to be destroyed by a major restructuring of the electorate: in effect, the destruction of the old industrial working class. Its destruction was not at first consciously willed. The disappearance of much of British industry in the early 1980s was not intended, but it was an acceptable result of the policies of deflation and deregulation; and was then turned to advantage. The ideological attack on the working class was, I think, willed. It involved an attack on the idea of the working class – indeed, on class as a concept. People were, via home ownership or popular capitalism, encouraged to think of themselves as not working class, whatever they actually were. The market thus disciplined some, and provided a bonanza for others. The economy was treated not as a productive mechanism but as a lottery, with many winners. The problem with such a policy was that it created a wildly unstable economy which Thatcher’s chancellors found increasingly difficult to control, and in which many of the apparent winners later became aggrieved losers.

In that sense, we’re all living in a world — linguistic and otherwise — that Thatcher created. Which means, I guess, that I will just have to go and see the damned movie.

Kodak & Eve RIP

The news today is that Kodak is preparing to file for bankruptcy and there can’t be a photographer of my generation who doesn’t feel an incredulous shudder at the prospect. It was an iconic company, and its products (especially Kodachrome) attained near-mythical status. (I mean to say, how many other commercial products have inspired a Paul Simon song?) Business school students will see the company’s demise as an illustration of Clayton Christensen’s idea of the Innovator’s Dilemma. Stranger still is the discovery that Kodak was a pioneer in the digital photography field (it built the first digital camera in 1975), and indeed its only current prospect of escaping bankruptcy seems to rely on selling its portfolio of patents, some of the most valuable of which are in digital imagery.

My hunch is that because the film-retailing and chemical processing sides of the business were so profitable and successful, those involved in that carried most weight in the company, and the engineers working on digital simply couldn’t persuade senior management to pay attention to a technology that would eventually cannibalise that core business. In a way, the same thing happened with the music industry when MP3 and the Net came along.

Today also brought news that Eve Arnold has died at the great age of 99. It sent me to Magnum (of which she was the first female member) to look again at their carousel of her most famous images. (The BBC also had a slideshow which includes the lovely picture of her sitting crosslegged on the ground shooting with a Leica.) The Guardian had a lovely piece by the film-maker Beeban Kidron, who became Arnold’s assistant at the age of 16.

“From Eve”, she writes,

“I learned: how to pack a suitcase – with a dress you could wear to a palace and shoes to run a marathon if required; how to look at pictures – for metaphor, form and truth; how to work – until it was done; how to be kind to your fellow artist – judge the endeavour not the result; and how to be a friend – through thick and thin; and how to laugh – uproariously and often.

I haven’t worked for Eve for more than 30 years – that privilege resides with Linni, her long-term colleague and assistant. But she became my adviser and friend. And when my son was very sick shortly after he was born, she did the one thing she knew how to do – she took his photograph – breaking her own rule of no baby pictures. It is one of those pictures, along side one of her with Marilyn, that adorn my office wall. “

The photograph shows the last roll of Kodak film that I possess.

The other side of the tracks

For over 150 years, Cambridge railway station was basically just one long platform (the third longest through-platform in England, according to Wikipedia). But it recently acquired a second platform, together with a bridge to access it. My train from London today stopped at the new platform.

When it first appeared in 1845 the station was way out in the countryside — the result of campaigning by the University to keep it away from the city centre, on the grounds that it would bring in ambitious whores from London, and/or enable students to visit same in the metropolis. Sadly, the station no longer serves such agreeable purposes and is now just a terminus for jaded commuters and academics like me going to and from meetings in London.

P-Day!

A resolution worth making — and keeping

Here’s a resolution for 2012 that’s worth making: write some real letters — you know, the ones written with pens on paper. Suki Bishop thinks they should be love letters, and picks out three stirring examples.

A great love letter isn’t perfect. It’s messy. It’s often bumbling and feverish and grammatically inept. But it’s everything the emoticon is not—specific, personal, unique.

Since, like the rest of us, you’re probably out of practice in this kind of thing, here are three tips from great writers—and lovers—of the past to help you write a love letter that transcends cliché.

1. Get personal. What does it mean to see your beloved? It means paying attention to the things that are unique to him or her. Make your beloved feel seen by describing specific habits, moments, objects, and/or physical attributes that only a lover would see, as Katherine Mansfield described to John Middleton Murry in 1917:

“When you came to tea this afternoon you took a brioche broke it in half & padded the inside doughy bit with two fingers. You always do that with a bun or a roll or a piece of bread—It is your way—your head a little on one side the while… [E]very inch of you is so precious to me. Your soft shoulders—your creamy warm skin, your ears, cold like shells are cold—your long legs and your feet that I love to clasp with my feet—[..] just below that bone that sticks out at the back of your neck you have a little mole [. . .] I could not bear that it should be touched even by a cold wind if I were the Lord.”

2. Command your beloved. While we might hate people telling us what to do, a command from a lover can convey a sense of confidence and urgency, as Virginia Woolf’s command to Vita Sackville-West in 1927:

“Look here Vita—throw over your man, and we’ll go to Hampton Court and dine on the river together and walk in the garden in the moonlight and come home late and have a bottle of wine and get tipsy, and I’ll tell you all the things I have in my head, millions, myriads—They won’t stir by day, only by dark on the river. Think of that. Throw over your man, I say, and come.”

3. Be playful…like Mozart, when he wrote to Constanze Mozart in 1789. Mozart wasn’t afraid to appear foolish. His sense of abandon conveys a love that is stronger than ego or pride.

“Dearest little wife, if only I had a letter from you! If I were to tell you all the things I do with your dear portrait, I think you would often laugh. For instance, when I take it out of its case, I say, ‘Good day, Stanzerl!—Good-day, little rascal, […], little turned-up nose, little bagatelle, Schluck and Druck,’ and when I put it away again, I let it slip in very slowly [… ] then just at the last, quickly, ‘Good night, little mouse, sleep well.’”

These great writers teach us not only about expressing love but also about patience, longing, and restraint.

Hotel room: December morning

Christmas tree

Tolkien: the unlikely revolutionary

I’ve never seen the point of Hobbits et al, so hadn’t really thought about J.R. Tolkien until (a) I was asked to buy a copy of the first volume of The Lord of the Rings for someone as a Christmas present and (b) I came on this piece by Adam Gopnik in the New Yorker. What captivated me were its opening paragraphs.

At Oxford in the nineteen-forties, Professor John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was generally considered the most boring lecturer around, teaching the most boring subject known to man, Anglo-Saxon philology and literature, in the most boring way imaginable. “Incoherent and often inaudible” was Kingsley Amis’s verdict on his teacher. Tolkien, he reported, would write long lists of words on the blackboard, obscuring them with his body as he droned on, then would absent-mindedly erase them without turning around. “I can just about stand learning the filthy lingo it’s written in,” Philip Larkin, another Tolkien student, complained about the old man’s lectures on “Beowulf.” “What gets me down is being expected to admire the bloody stuff.”

It is still one of the finest jests of the modern muses that this fogged-in English don was going home nights to work on perhaps the most popular adventure story ever written, thereby inventing one of the most successful commercial formulas that publishing possesses, and establishing the foundation of the modern fantasy industry.