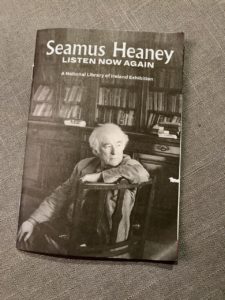

Remembering Seamus Heaney

We were in Dublin last weekend and were accordingly able to visit the celebration of Seamus Heaney organised by the National Library of Ireland, to which he had donated his papers before he died. (He piled them all into his car and drove them to the Library.) It’s in a wing of the wonderful old Irish Parliament building opposite Trinity College, and is an inspired piece of curation by Geraldine Higgins. It has four themes: Excavations, covering Heaney’s early work; Creativity, looking at how he worked; Conscience on how he wrestled with what it meant to be a poet from Northern Ireland during the thirty years of violent conflict now known as ‘the Troubles’; and Marvels about his later work exploring some of the ways in which he circled back to the relationships of his childhood and youth.

It’s a wonderful exhibition which brings out the imaginative genius of a great poet. What was striking about Heaney (or ‘Famous Seamus’ as my countrymen dubbed him in an unnecessary attempt to stop him getting a big head) was the way he managed to be both earthed and sublime. His poetry is accessible to everyone and moving; and yet he was also a real scholarly heavyweight — a translator of Virgil and of Beowulf, for example, as well as a holder of professorial chairs at Harvard and Oxford. (Evidence: his Nobel lecture or his Oxford lectures, The Redress of Poetry.)

He’s my favourite poet, and I spent some of the exhibition close to tears while at the same time marvelling at the arc of his life. It was lovely to see marked-up drafts of his poems at various stages in their composition. And he had such nice handwriting — light and crystal clear. Also (something dear to my heart) he always wrote with a fountain pen.

The nicest things came at the end: readings of his unconventional love poem to his wife Marie after they were married. His final text message to her just before he died: noli timere (don’t be afraid). And a recording of him reading my favourite poem, Postscript, celebrating the magical coastline of the Burren in Co Clare.

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit

By the earthed lightening of flock of swans,

Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white,

Their fully-grown headstrong-looking heads

Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.

Useless to think you’ll park or capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

Unmissable. And it’ll run for three years.

Quote of the Day

“Don’t attribute to stupidity what can be explained by incentives”

RIP Clayton Christensen, who coined the term ‘disruptive innovation’.

Kim Lyons wrote a nice obituary in The Verge.

Scores of notable tech leaders have for years cited Christensen’s 1997 book The Innovator’s Dilemma as a major influence. It’s the only business book on the late Steve Jobs’ must-read list; Netflix CEO Reed Hastings read it with his executive team when he was developing the idea for his company; and the late Andy Grove, CEO of Intel, said the book and Christensen’s theory were responsible for that company’s turnaround. After summoning Christensen to his office to explain why he thought Intel was going to get killed, Grove was able to grok what to do, Christensen recalled:

“They made the Celeron Processor. They blew Cyrix and AMD out of the water, and the Celeron became the highest-volume product in the company. The book came out in 1997, and the next year Grove gave the keynote at the annual conference for the Academy of Management. He holds up my book and basically says, “I don’t mean to be rude, but there’s nothing any of you have published that’s of use to me except this.”

Personally, I don’t think he ever recovered from Jill Lepore’s devastating critique of his theories in the New Yorker.