Sometimes, things happen that restore one’s faith in humanity. Here’s a report of one such event.

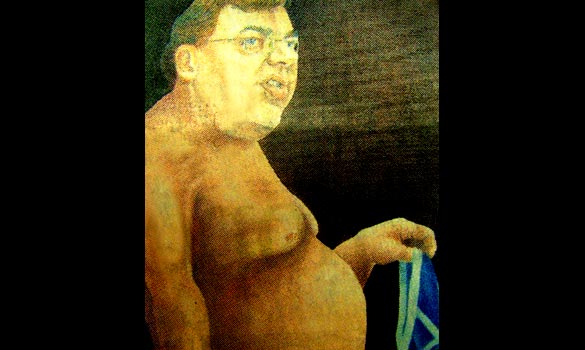

It seems that two unorthodox portraits of Brian Cowen, the Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister), suddenly appeared in two of Dublin’s leading galleries. One in the National Gallery showed the Taoiseach on the toilet, and another in the Royal Hibernian Gallery (above) showing him holding his Y-fronts. According to the report, the pictures

appeared mysteriously in Dublin among paintings of the country’s other famous citizens in more decorous poses.

The Irish media speculated that the prankster had created the artworks in an attempt to lift the nation’s spirits at a time of deep economic gloom. Judging by the chuckles of visitors and comments inundating the blogosphere, the stunt worked.

“Biffo on the bog”, was one gleeful response, referring to the Taoiseach by his nickname, which stands for “Big Ignorant F***er from Offaly”.

The artist reportedly walked calmly into the National Gallery carrying a shoulder bag. He then affixed a prepared caption for the picture to a free space among portraits of Michael Collins, William Butler Yeats and Bono, before hanging his canvas, undisturbed by security.

There’s been the most ludicrous over-reaction by the government to this — as reported by, e.g. the Irish Times. RTE, the national TV station, cravenly apologised for reporting the incident after a complaint from the government’s Press Secretary (who happens to be a namesake of mine). What it shows, of course, is the power of ridicule. The moral authority of the Catholic church in Ireland never recovered from the revelation that the Bishop of Kerry had not only been screwing a handsome dame (and fathering a child) but that he had been doing it in the back of a Lancia saloon! This led to a wonderful explosion in Bishop Casey jokes (e.g. Q. “What’s the correct form of address for the Bishop of Kerry?” A. “Dad.”) Cowen was already looking ridiculous as a result of the implosion of the Irish banking system. Now he’s a real laughing stock.