Well, well. So Charles D was a perfectly normal undergraduate for his day.

Two hundred years after Charles Darwin’s birth, historians have gained new insight into his days as a student at Cambridge after unearthing bills that record intimate details of how he spent his money.

The revolutionary scientist was, it would appear, ahead of his time in his willingness to pay extra to supplement his daily intake of vegetables. And, as one would expect of a 19th-century gentleman, he was happy to pay others to carry out menial tasks for him, such as stoking his fire and polishing his shoes.

But there is little to suggest that he bought many books, or that he did much else to further his studies. The evolutionist famously spent little of his time studying or in lectures, preferring to shoot, ride and collect beetles.

The records, which were found in six previously overlooked college books, are due to be published online tomorrow on the Complete Works of Charles Darwin website (darwin-online.org.uk). They allow historians to pinpoint the date of his arrival at Christ’s College (26 January 1828), as well as providing previously unknown detail of his undergraduate life.

Darwin’s time at Cambridge, from 1828 to 1831 – which he would later describe as “the most joyful of my happy life” – is also one for which there is a comparative shortage of information. “Before this, we didn’t really know very much about Darwin’s daily life at Cambridge at all,” said Dr John van Wyhe, director of the Darwin website. “It had been assumed that there were no significant traces of his time here left to discover, which meant that we were short of information about one of the most formative parts of his life.

Now, in his 200th anniversary year, we have found a real treasure trove right in the middle of Cambridge.”

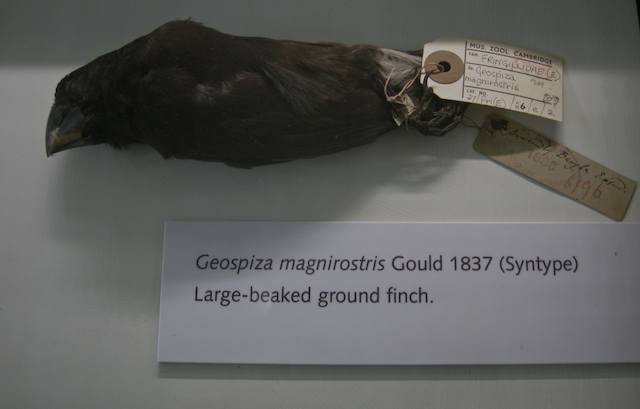

As it happens, I was in the Zoology Museum the other night, at the launch of the Cambridge Science Festival, when I came on some display cases showing some of Darwin’s finches (above) and the beetle collection he amassed during his time as a student (below).

There’s something magical about coming face to face with objects like this. They have the ‘aura’ that Walter Benjamin used to go on about in The Work of Art in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction.