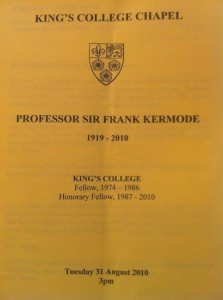

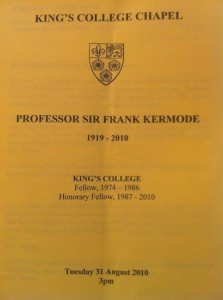

Frank Kermode’s funeral took place yesterday in King’s chapel. It was a small affair (there will be a memorial service later) which was elegant, moving, celebratory and only slightly elegaic. I think he would have approved. Afterwards, there was a splendid tea in the Senior Combination Room. His friends Anthony Holden, Ursula Owen, Karl Miller and John Sutherland spoke, and Tony and Ursula read a couple of poems which seemed spot on for the occasion.

I felt for both of them, for they had known and loved Frank more intimately and for longer than most of us, and these things are always, in the end, an ordeal. Tony chose to read the sonnet he’d written for Frank’s 80th birthday:

Where once you were a name on spines of books

Read, marked and learned in duly franker mode,

Of late you are a friend with knowing looks,

Warm heart, wise counsel, welcoming abode.

Together we have stalked the Stratford bard,

Hip-flasked at Highbury, chalked the Savile baize,

Wept at the opera, watched Lara taking guard,

Set towns from Yale to Barga all ablaze.

Your students know the learned, measured sage,

Your readers the insightful polyglot,

I the chimes-at-midnight chum, sans age

And for all time — whose winged chariot,

refusing to believe you’re just four score,

Is posting flight-plans for a good few more.

Nobody could have known when those words were written that Frank had another fruitful decade ahead. And what a decade! There was a small ripple of astonishment when Tony reminded his audience that Frank published ten books in that last decade. Imagine it: a book a year — and the funny thing was that he always swore that the one he was working on at the moment would definitely be his last. When he knew his time was coming to an end, he briefly contemplated writing a book about dying but decided against because he wouldn’t be able to finish it! This was, after all, the man who wrote that memorable book, The Sense of an Ending.

At the tea afterwards, I ran into an old friend who told me that she had just been re-reading that particular book. She had first read it as a young woman many years ago and it had whistled over her head then. But now, she said, it made perfect sense. It’s strange how we often realise the significance of things — and of people — too late.

Ursula told a lovely story about a trip she and Frank had gone on together — to the Yeats Summer School in Sligo, where he had been invited to lecture. When they settled into their seats on the plane, Frank opened his folder and realised that he’d brought the wrong text. So they checked into their hotel and he then calmly reconstructed the missing lecture, walked out and delivered it.

Afterwards they drove down to Gort, to visit Coole Park — the home of Lady Gregory, Yeats’s great friend — and Thoor Ballylee, the tower that Yeats restored (and which, IMHO, is still one of the most magical spots in Ireland). Then they returned to Coole (where the demesne remains even though the house has long been demolished) and stood by the lake, counting the swans. She then read Yeats’s The Wild Swans at Coole, which is one of his loveliest and most accessible poems.

It begins:

The Trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;

upon the brimming water among the stones

Are nine and fifty swans.

On that magical day when they visited, Ursula said, there were only nine swans. But in an odd, poetic way, I thought, that seemed to fit.

At the end of his eulogy, Tony said something that rang true for all of us. “What I did to earn Frank’s regard”, he said, “I’ll never know”. Me neither. To be granted the friendship of such a great man was a wonderful privilege. So I’ll just count it as one of my blessings and leave it at that.