If you wanted a demonstration of the naiveté of traditional media in relation to networked technology, then you be hard pressed to better the Wall Street Journal’s new ‘whistleblowing’ facility, SafeHouse.

Documents and databases: They’re key to modern journalism. But they’re almost always hidden behind locked doors, especially when they detail wrongdoing such as fraud, abuse, pollution, insider trading, and other harms. That’s why we need your help.

If you have newsworthy contracts, correspondence, emails, financial records or databases from companies, government agencies or non-profits, you can send them to us using the SafeHouse service.

Stirring stuff, eh? But let’s have a look at the Terms and Conditions:

Submission Options

SafeHouse provides three options to submit documents and other information:

1. Standard SafeHouse: The standard online submission form can be used to provide any relevant documents and information along with your contact information. If you choose this option, and provide us with your contact information, Dow Jones retains the right to use the material and any other information you provide about yourself as it sees fit (as described more fully below in the Limitations section), and does not make any representations regarding confidentiality.

2. Anonymous SafeHouse: If you prefer not to include any contact information, and instead remain anonymous, you can still provide information through this form. If you choose this option, Dow Jones retains the right to use the material and any other information you provide as it sees fit (as described more fully below in the Limitations section), and does not make any representations regarding confidentiality. In an effort to attach an added level of security, we have designed this online submission form to minimize the amount of identifying information we or others can access. Despite efforts to minimize the information collected, we cannot ensure complete anonymity. For additional security, you can use certain online tools, such as The Tor Project (https://www.torproject.org), to submit any documents or information. When used correctly, these services and software can block the recipient of information from knowing the source of that information. More information on this topic is available here. You agree that we are not responsible for, and do not control, any such third party services and software that attempt to provide anonymity.

3. Request Confidentiality: If you would like us to consider treating your submission as confidential before providing any materials, please make this request through this online submission form. Please note that until we mutually decide to enter into a confidential relationship, any information you send to us (including contact information) can be used for any purpose, as outlined in point 1 above, and described more fully below in the Limitations section). If we enter into a confidential relationship, Dow Jones will take all available measures to protect your identity while remaining in compliance with all applicable laws.

You understand that regardless of the method of submission, we are unable to ensure the complete confidentiality or anonymity of anything you send to us. As a result, please use discretion in contacting us and providing us with information. You use this service at your own risk.

[…]

Except when we have a separately negotiated confidentiality agreement pursuant to the “Request Confidentiality” Section above, we reserve the right to disclose any information about you to law enforcement authorities or to a requesting third party, without notice, in order to comply with any applicable laws and/or requests under legal process, to operate our systems properly, to protect the property or rights of Dow Jones or any affiliated companies, and to safeguard the interests of others.

(Emphasis added.)

According to the Guardian story dated 6 May, “uploading from Tor did not work on Thursday or Friday when tested by security researchers”.

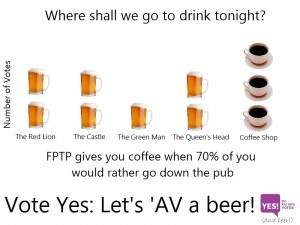

So, here’s my question: if you were a whistleblower would you feel more comfortable sending stuff to (a) Wikileaks, or (b) the Wall Street Journal?

What this highlights, of course, is the difficulties established media organisations have in dealing with this stuff. The whole point of Wikileaks-type operations is that they have no assets to be seized, no executives to be subpoenaed, no shareholders to be intimidated, no publications to be injuncted, no advertisers to withdraw their support. It’s interesting to see that several traditional outfits (the NYT and Guardian are rumoured to be planning their own “secure” submission channels for leaked material, and Al Jazeera already what it calls its Transparency Unit). What remains to be seen is whether any one of them will be seen as deserving the trust of whistleblowers.