Quote of the Day

“Mark Twain and I are in very much the same position. We have to put things in such a way as to make people, who would otherwise hang us, believe that we are joking.”

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Sharon Shannon | Blackbird

Link

A phenomenal musician who lights up every venue she plays.

Long Read of the Day

Lina Khan’s Battle to Rein in Big Tech

Classic New Yorker profile by Sheelah Kolhatkar of one of the most interesting young women in America, who is now Chair of the FTC. If you don’t know about Khan, then this is a good place to start.

After years spent publishing research about how a more just world could be achieved through a sweeping reimagining of anti-monopoly laws, Khan now has a much more difficult task: testing her theories—in an arena of lobbyists, partisan division, and the federal court system—as one of the most powerful regulators of American business. “There’s no doubt that the latitude one has as a scholar, critiquing certain approaches, is very different from being in the position of actually executing,” Khan told me. But she added that she intends to steer the agency to choose consequential cases, with less emphasis on the outcomes, and to generally be more proactive. “Even in cases where you’re not going to have a slam-dunk theory or a slam-dunk case, or there’s risk involved, what do you do?” she said. “Do you turn away? Or do you think that these are moments when we need to stand strong and move forward? I think for those types of questions we’re certainly at a moment where we take the latter path.

“There’s a growing recognition that the way our economy has been structured has not always been to serve people,” Khan went on. “Frankly, I think this is a generational issue as well.” She noted that coming of age during the financial crisis had helped people understand that the way the economy functions is not just the result of metaphysical forces. “It’s very concrete policy and legal choices that are made, that determine these outcomes,” she said. “This is a really historic moment, and we’re trying to do everything we can to meet it.”

The inner lives of cats: what our feline friends really think about hugs, happiness and humans

Nice piece by Sirin Kale on a question that perplexes most cat-owners: what does their pet think of them? (My own answer: not much.)

Despite the fact that cats are the most common pet in UK households after dogs, we know relatively little about them. This, says Dr Carlo Siracusa of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, “is partly due to practical problems.”

Dogs are easy to study: you can take them to a lab and they will be content. But cats are intensely territorial creatures. “The behaviour of a cat is so modified by its environment that if you move it to a laboratory,” says Siracusa, “what you’ll see is not really reflective of what the normal behaviour of the cat is.”

But there is another reason that cats are under-researched. “There’s a stigma,” says Siracusa. Cats have been unfairly maligned through much of human history. In the middle ages, cats were thought of as the companions of witches, and sometimes tortured and burned. “They have been stigmatised as evil because they are thought to be amoral,” says the philosopher and writer John Gray, author of Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life. “Which in a sense, cats are – they just want to follow their own nature.”

Thanks to Rob for spotting it.

Footnote: John Gray’s book on the subject of cats is lovely, btw. It opens with a story about a philosopher friend who believed that he had trained his cat to be a vegan. (He omitted to notice that his cat went out every night.)

This philosopher, Gray writes,

only showed how silly philosophers can be. Rather than trying to teach his cat, he would have been wiser if he had tried learning from it. Humans cannot become cats. Yet if they set aside any notion of being superior beings, they may come to understand how cats can thrive without anxiously inquiring how to live.”

Amen.

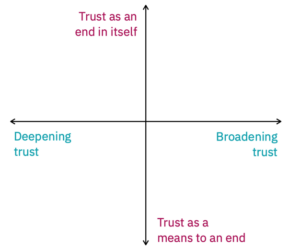

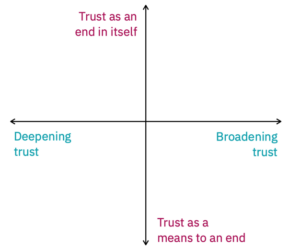

Chart of the Day

Useful way of thinking about a topic that is usually smothered in vagueness (not to say vacuity). It comes from a new report by the Reuters Institute looking at the trade-offs news organisations navigate when trying to increase trust in news. It’s the fourth instalment from the Institute’s ‘Trust in News’ Project and is based on our conversations with 54 journalists and newsroom managers in Brazil, India, the UK and the US.

It’s an interesting and worrying report — worth reading in full if you work in media. The nub of the problem, unsurprisingly, is that in an industry which is fighting for its life (in the sense of economic viability) ‘trust’ or trustworthiness may come down the list of priorities.

Here are some of the authors’ reflections on what they found.

What we find here is nuanced. On the one hand, these conversations reveal a great deal of pessimism and concern about the impact of external forces on news organisations’ abilities to forge trusting relationships with their audiences. Most focused on what they see as the highly corrosive impact of negative criticism on digital platforms, which they increasingly depend on to broaden their reach, but which also serve to amplify bad-faith criticism about independent reporting and the institution of journalism more generally. Many also expressed grave concern about the level of vitriol and toxicity in these spaces, some of it egged on by political leaders with their own reasons for antagonising the press.

Some of these concerns are well-supported by academic research, especially the important role played by elite cues, polarisation, and the distance audiences may feel from the professional practices of journalism. Others centre on very real risks that have yet to be the subject of much academic investigation. However, it is important to recognise that while many journalists may feel relatively powerless to move the needle on trust (and much academic research suggests external factors are more important for trust in news than the things individual journalists or news organisations have control over), much of the public sees journalism and news media as powerful institutions (see, for example, Palmer 2017) and are unlikely to accept that the root of the problem lies elsewhere, or that they have few options at their disposal. Thus, giving up on building trust may look like a lack of real interest in the issue.

Supporting Wikipedia

I use Wikipedia a lot, and always have. And I donate to it regularly. If, like me, you write newspaper columns, a link to the relevant Wikipedia entry often frees one from having to break the narrative by pausing to explain something in detail. Regular financial donations are a way of expressing my appreciation for using it as a resource.

In the early days, though, some people — especially academics — were very sniffy about it. I remember an occasion when the Vice-Chancellor of an ancient university made a dismissive comment about Wikipedia and then was astonished to find a very distinguished Fellow of the Royal Society interrupting her to say that the Wikipedia pages on his arcane speciality were the most accurate and up to date reference on the subject. Why? Because he had written them. Result: one very embarrassed Vice-Chancellor.

As time went on, I noticed that people tended to have two kinds of views about it — (a) dismissive because they had found a glaring error in a page; or (b) gushing with praise. I developed a strategy for dealing with both types.

For (a), the dialogue would go something like this.

Me: “So you’ve found a glaring error on a subject you know about?”

Critic: “Yes. Elementary mistake”.

Me: “So why haven’t you corrected it?”

Critic: Flustered (sometimes), irritated (often), defensive (much too busy)

For (b), things were generally simpler.

Me: “I’m glad you think highly of Wikipedia”.

Gusher: “Yes, it’s wonderful, isn’t it?”

Me: “So when did you last make a donation to ensure that it keeps going?”

Gusher: Er…

Correction

The link to Colin Dickey’s essay on Mrs Galloway the other day was faulty. The correct link is: https://lithub.com/the-work-of-living-goes-on-rereading-mrs-dalloway-during-an-endless-pandemic/

Apologies for the error.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!