This is not a stool

(With apologies to Magritte.)

(With apologies to Magritte.)

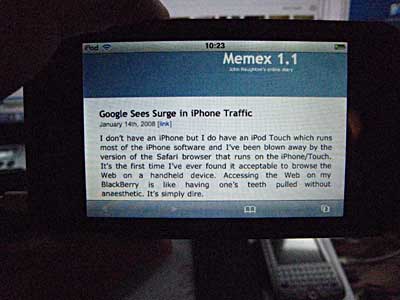

Google Sees Surge in iPhone Traffic

I don’t have an iPhone but I do have an iPod Touch which runs most of the iPhone software and I’ve been blown away by the version of the Safari browser that runs on the iPhone/Touch. It’s the first time I’ve ever found it acceptable to browse the Web on a handheld device. Accessing the Web on my BlackBerry is like having one’s teeth pulled without anaesthetic. It’s simply dire.

Looks like I’m not alone in this:

On Christmas, traffic to Google from iPhones surged, surpassing incoming traffic from any other type of mobile device, according to internal Google data made available to The New York Times. A few days later, iPhone traffic to Google fell below that of devices powered by the Nokia-backed Symbian operating system but remained higher than traffic from any other type of cellphone.

The data is striking because the iPhone, an Apple product, accounts for just 2 percent of smartphones worldwide, according to IDC, a market research firm. Phones powered by Symbian make up 63 percent of the worldwide smartphone market, while those powered by Microsoft’s Windows Mobile have 11 percent and those running the BlackBerry system have 10 percent.

The iPhone has taken the frustration out of browsing on a mobile phone, said Charles Wolf, an analyst with Needham & Company.

Other companies confirmed the trends, if not the specific data, observed by Google. Yahoo, for instance, said iPhones accounted for a disproportionate amount of its mobile traffic. And AdMob, a firm that shows billions of ads on mobile Web sites every month, said it saw traffic from iPhones surge drastically around Christmas.

“Consumers are going to demand Internet browsers” as good as Apple’s, said Vic Gundotra, a Google vice president who oversees mobile products…

The stats are significant: Google is seeing almost as much traffic from a device that has 2 per cent of the phone market as from Symbian phones which have 63 per cent of the market. There’s a lesson there, Nokia.

Forward to the past…

… or is it back to the future? Lovely column by Stephen Fry on walled gardens and social networking…

I am old enough to remember Prestel and the original bulletin boards and “commercial online services” Prodigy, CompuServe and America Online. These were closed communities. You paid a subscription, dialled in and connected. You made new friends and you chatted in “rooms” designated for the purpose according to special interests, hobbies and propensities. CompuServe and AOL were shockingly late to add what was called an “internet ramp” in the 90s. This allowed those who dialled up to go beyond the confines of the provider’s area and explore the strange new world of the internet unsupervised. AOL offered its members a hopeless browser and various front ends that it hoped would keep people loyal to its squeaky-clean, closed world. This lasted through the 90s as it covered the planet in CDs in an attempt to recruit subscribers. A lost cause, naturally, and the company ended up as little more than an ordinary ISP. Made millions for Steve Case on the way as AOL merged with Time Warner, but that’s another story.

Opening and closing like a flower

My point is this: what an irony! For what is this much-trumpeted social networking but an escape back into that world of the closed online service of 15 or 20 years ago? Is it part of some deep human instinct that we take an organism as open and wild and free as the internet, and wish then to divide it into citadels, into closed-border republics and independent city states? The systole and diastole of history has us opening and closing like a flower: escaping our fortresses and enclosures into the open fields, and then building hedges, villages and cities in which to imprison ourselves again before repeating the process once more. The internet seems to be following this pattern…

Thanks to Pete for the link.

Money for jam?

No — this is not a story about a hedge fund manager, but about a guy who founded an online dating site.

MARKUS FRIND, a 29-year-old Web entrepreneur, has not read the best seller “The 4-Hour Workweek” — in fact, he had not heard of it when asked last week — but his face could go on the book’s cover. He developed software for his online dating site, Plenty of Fish, that operates almost completely on autopilot, leaving Mr. Frind plenty of free time. On average, he puts in about a 10-hour workweek.

For anyone inclined to daydream about a Web business that would all but run itself, two other details may be of interest: Mr. Frind operates the business out of his apartment in Vancouver, British Columbia, and he says he has net profits of about $10 million a year. Given his site’s profitable advertising mix and independently verified traffic volume, the figure sounds about right…

Bully for him!

Deaths in Iraq: the numbers game

From openDemocracy…

A third assessment of post-invasion violent deaths in Iraq was published on 9 January 2008 by the New England Journal of Medicine, a prestigious platform for medical research and scientific debates edited in Boston, Massachusetts. The lead article in the journal – “Violence-Related Mortality in Iraq from 2003 to 2006” – reports the results of an inquiry by the Iraq Family Health Survey Study Group (IFHS), involving collaboration between national and regional ministers in Iraq and the World Health Organisation (WHO). It finds that 151,000 (between 104,000 and 220,000) people died from violence in Iraq between March 2003 and June 2006…

Why are British media so fascinated by the US primaries?

I’ve been wondering for weeks why the BBC and the UK newspapers are devoting so much attention to the primaries. Today, in a perceptive piece, my Observer colleague Peter Preston puts forward an interesting conjecture:

Two things follow. One is a new connection that needs making more clearly. British editors are more fascinated by this presidential race than ever, and not just because it comes with black or feminist drum rolls of history attached. This time, for the Mail, Times, Guardian and Telegraph in particular, there are millions of American readers of their websites to be wooed and served, unique users with ad potential attached. So, who wins in November matters much closer to home.

When the Mail lays into Hillary and Matt Drudge’s site carries that copy, the hits grow exponentially. If Mrs Clinton makes it to the Oval office, the Telegraph would reckon to pick up web readers as it leads a conservative attack that consensual US papers might initially shy away from. If Obama or Clinton win, then the Guardian, which has scored so many points by belabouring George Bush, has a different climate to work in.

And the other thing – on behalf of British readers and viewers at least – is to wonder how many miles and hours of faraway, self-cancelling stuff about moods and hunches the market can endure before the real and abiding election starts next autumn…

The green machine that made Intel see red

This morning’s Observer column…

An interesting package arrived in my household the other day: a small bright green-and-white laptop with a built-in carrying handle. It looks as if it has been designed by Fisher-Price, an impression reinforced by two little ‘ears’ which, when unclipped, double as wi-fi antennae. The 7.5in screen rotates and folds back on itself to form a kind of tablet, rather like those pricey Toshiba laptops only Microsoft salespeople can afford…

BECTA: Don’t upgrade to Vista

Wow! Peter Sayer, of IDG News Service reports on BECTA’s considered opinion of Microsoft Vista:

British schools should not upgrade to Microsoft’s Vista operating system and Office 2007 productivity suite, the British Educational Communications and Technology Agency (BECTA) said in a report on the software. It also supported use of the international standard ODF (Open Document Format) for storing files.

InfoWorld PodcastSchools might consider using Vista if rolling out all-new infrastructure, but should not introduce it piecemeal alongside other versions of Windows, or upgrade older machines, said the agency, which is responsible for advising British schools and colleges on their IT use.

“We have not had sight of any evidence to support the argument that the costs of upgrading to Vista in educational establishments would be offset by appropriate benefit,” it said.

The cost of upgrading Britain’s schools to Vista would be £175 million ($350 million), around a third of which would go to Microsoft, the agency said. The rest would go on deployment costs, testing and hardware upgrades, it said.

Even that sum would not be enough to purchase graphics cards capable of displaying Windows Aero Graphics, although that’s no great loss because “there was no significant benefit to schools and colleges in running Aero,” it said.

As for Office 2007, “there remains no compelling case for deployment,” the agency said in its full report, published this week.

The report (pdf) is available from here.

The relevant bit of the Executive Summary reads:

The key recommendations emanating from this final report (all of which we cover in further detail in the report) are as follows.

We advise that upgrading existing ICT systems to Vista is not recommended and that mixed Windows-based operating-system environments should be avoided. We believe that Vista can be considered where new institution-wide ICT provision is being planned Recognising the limitations regarding Microsoft’s implementation of the ODF standard and the limited uptake of Microsoft’s new Office 2007 file format, we recommend that in the short term users should continue to use the older Microsoft binary formats (such as .doc) Schools and colleges should make students, teachers and parents aware of the range of ‘free-to-use’ products (such as office productivity suites) that are available, and how to access and use them. The ICT industry should be pro-active in facilitating easier access to ‘free-to- use’ office productivity software.

Note: BECTA is the government-funded organisation which advises the UK educational sector on ICT.

Quote of the day

At the end of 10 thrilling and memorable days in American electoral politics, we should recall the words of the late Daniel Patrick Moynihan – who was, by coincidence, Hillary Clinton’s predecessor as senator for New York. People are fully entitled to their own opinions, he observed, but they are not entitled to their own set of facts.

Martin Kettle, writing in today’s Guardian.