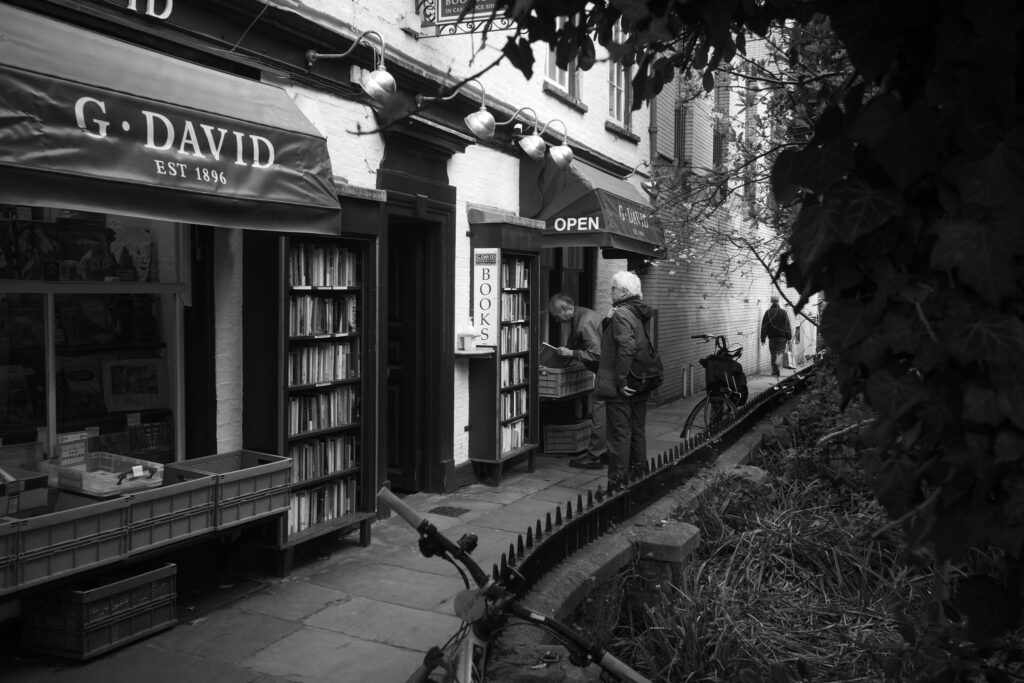

David’s

Along with Shakespeare and Company in Paris, and Paludan in Copenhagen, David’s in Cambridge is one of the world’s loveliest bookshops. The apartment above it is where John Maynard Keynes and his wife Lydia lived when they were in Cambridge. (As a married couple, I guess they couldn’t live in his college, King’s), though I guess the college owned the apartment (and probably the entire city block.). Anyway, it’s a delightful place if you’re a bookish type.

Quote of the Day

”Whom the mad would destroy, first they make gods.”

- Bernard Levin

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Jerry Garcia | Don’t You Let Deal Go Down

Long Read of the Day

america against china against america

Fascinating essay by Jasmine Sun, a smart blogger who describes herself as doing anthropology in the tech industry centred on Silicon Valley. This is an account of a visit she and some colleagues recently made to China hoping “to see China’s technological achievements firsthand”.

Here’s a sample:

Chinese engineers also seem more practical than their American counterparts. They’re here to build tech and make money; risk management is for bureaucrats; policy is only relevant insofar as it helps or hurts your work. This is something I think Westerners often get wrong. If you live in a single-party state, you are, on average, less ideological yourself. The politics have already been decided—no point wasting extra cycles coming up with something new.

Overall, I left my conversations with Chinese technologists feeling real admiration: they faced unimaginable uphill battles from US restrictions and a competitive domestic market. Low margins and a thin capital environment don’t stop people from shipping high-quality work. Sure, such rhetoric could be performative chest-puffing. But their mindset was locked in. One could argue that Chinese are trained their whole lives for this—competition only makes them stronger. As Charles put it: They had the fucking juice.

It’s a long read, but consistently interesting because she’s such a sharp observer That’s the anthropologist for you, I guess. I liked many of her small insights. Example for conversations with Chinese people who came back from the US “For some I spoke with,” she writes, “I sensed that the quality of life gap made them more skeptical of liberal democracy. The Chinese system does stupid things, but so does America, they implied. At least the trains work.”

It was also interesting to read it alongside Dan Wang’s new book.

My commonplace booklet

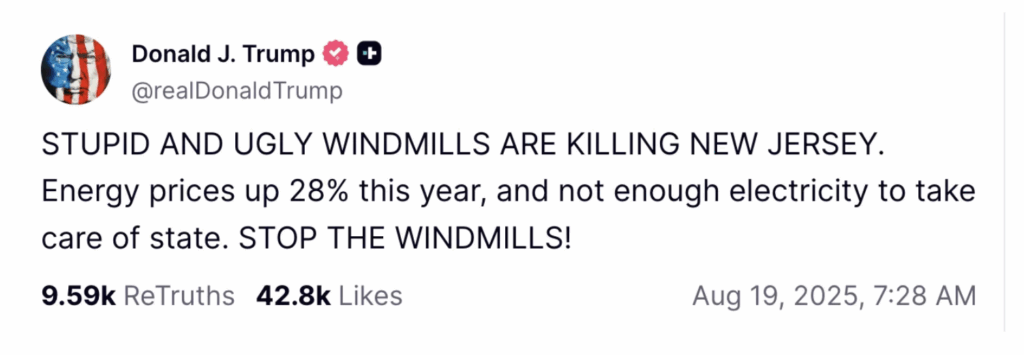

Tilting at Windmills

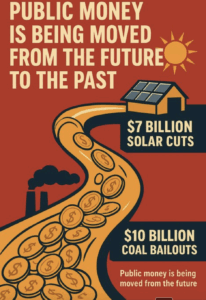

There is one respect (and one only) in which Trump reminds me of Cervantes’s hero, Don Quixote: both are hostile to windmills. Don Q saw them as giants rather than machines. Trump has a deep and irrational hatred of them because they threaten the fossil fuel industries to which he is viscerally attached. But the really funny thing about his tweet, according to Paul Krugman, is that New Jersey has no windmills. After taking office, he promised to halve electricity prices. Currently they’re going up, partly because of the demands of tech companies and AI — and possibly also because of the stress placed on the grid by crypto, in which Trump has a massive stake. Truly, you couldn’t make this stuff up.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!