Tree, RIP

Quote of the Day

”God is really only another artist. He invented the giraffe, the elephant and the cat. He has no real style. He just goes on trying other things.” * Picasso

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Oscar Peterson | C Jam Blues | Live in Denmark,1964.

Link

Oscar on Piano, Ray Brown on Bass, Ed Thigpen on Drums

Long Read of the Day

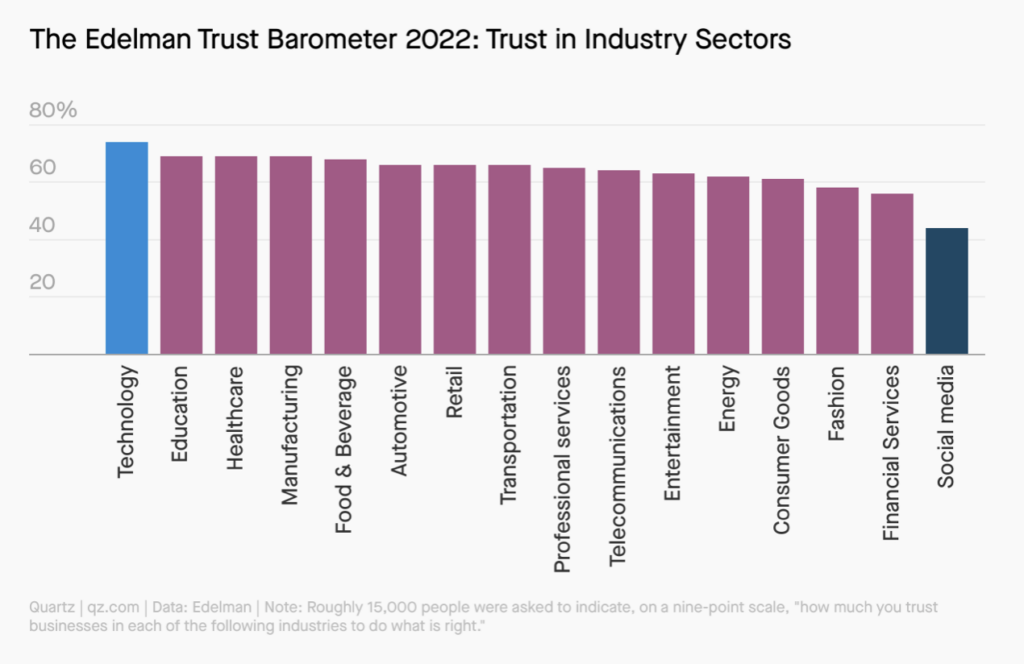

Amid the hype over Web3, informed skepticism is critical

It is, and this is a pretty good example. It’s by Elizabeth Renieris, a researcher on the ethical and human rights impacts of technology in Notre Dame , Harvard and elsewhere. I’ve been collecting critiques of the Web 3 madness, and this was a welcome find.

“Increasingly apparent in the Web3 discourse,” she writes,

is a kind of imaginative obsolescence: As one vision of the future rapidly replaces the next, the technologies and systems now in place suffer decay and disrepair. Our imaginations and resources are once again diverted from fixing or rehabilitating what exists. Meanwhile, familiar problems, inevitably, resurface. Imaginative obsolescence also upends efforts at effective technological governance — and perhaps that is exactly the point.

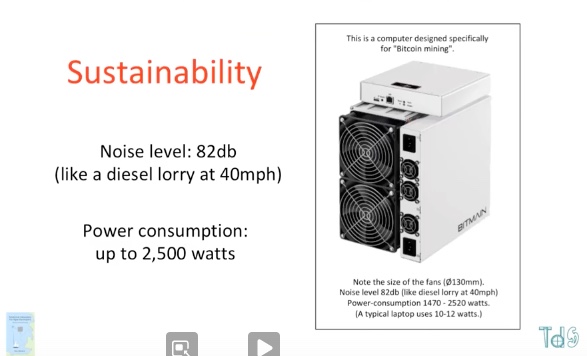

Like its predecessors (Web 1.0, “the era of static webpages,” and 2.0, the internet of social media and user-driven content), Web3 is imagined as being apolitical, open, decentralized and inclusive, its proponents even using the same rhetoric as the cyberlibertarians of John Perry Barlow’s day. This ethos — characterized by free speech absolutism and free market ideals — has enabled all manner of online harms, including rampant mis- and disinformation, racism, discrimination, hate speech and harassment, concentrations of power, toxic business models and limited accountability. While it may be early, Web3 is quickly encountering many of the same challenges, even as it purports to be immune to them.

A good — and timely — read.

And if you’d like a constantly-updated display cabinet of Web 3 madnesses and scandals, see software developer Molly White’s Web 3 is going just great site.

Photographer finds polar bears that took over abandoned buildings

This remarkable image on the photography site Petapixel made lots of us sit up, first of all because of its haunting painterly quality, and secondly because everyone knows that getting close enough to polar bears to take a picture like that is a bad career move.

The explanatory blurb reads:

A Russian photographer has captured a fascinating series of photos showing polar bears that have taken over the abandoned buildings of a meteorological station on an island between Russia and Alaska.

In September 2021, photographer Dmitry Kokh traveled through islands in the Chukchi Sea, a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean that sits between Russia and Alaska.

“Being the farthest and most Eastern part of Russian Arctic, this place is very hard to get but also difficult to forget,” Kokh writes. “We traveled by the sailing yacht along the coast and covered more than 1,200 miles of untouched landscapes, villages lost in time, spots with various fauna and seas full of life.”

The Petepixel post included ten more photographs taken by Kokh, some taken from vantage points suicidally close to the bears, and each one more charming than the last. There’s something about polar bears that evokes the same emotions in human animals that pictures of cats and Koala bears do.

Needless to say, some of the comments below the story were sceptical. Surely the image was photoshopped? “At least 4 grown bears all together in this house is surprising”, said another. “Also wondering how this photographer got so close to them. Probably just a brave/lucky person. Is it likely the photographer is keeping these as pets of some sort? Or luring them into the house with food?” And so on.

Fortunately, the penny dropped quickly. The pictures were stills from footage shot by a drone. It’s worth watching (three minutes), not least because it’s a reminder of how good drone footage can be nowadays — as anyone who reads Quentin’s blog will know.

My commonplace booklet

Standing on the edge of a cliff, I took my time setting up my tripod and camera in anticipation of a sunset. The light would soon be bathing the mountains in front of me, illuminating the confluence of the Indus and Zanskar rivers. One of the most beautiful sights my eyes had ever seen, the two tributaries have very distinct colors at the place where they join. The Indus is jade green, while the Zanskar has cyan blue hues. I had big plans for capturing the magic of this place in a photograph. After futzing around with my gear for a while, I had my composition and focus set. All I had to do was press the shutter when the time was right.

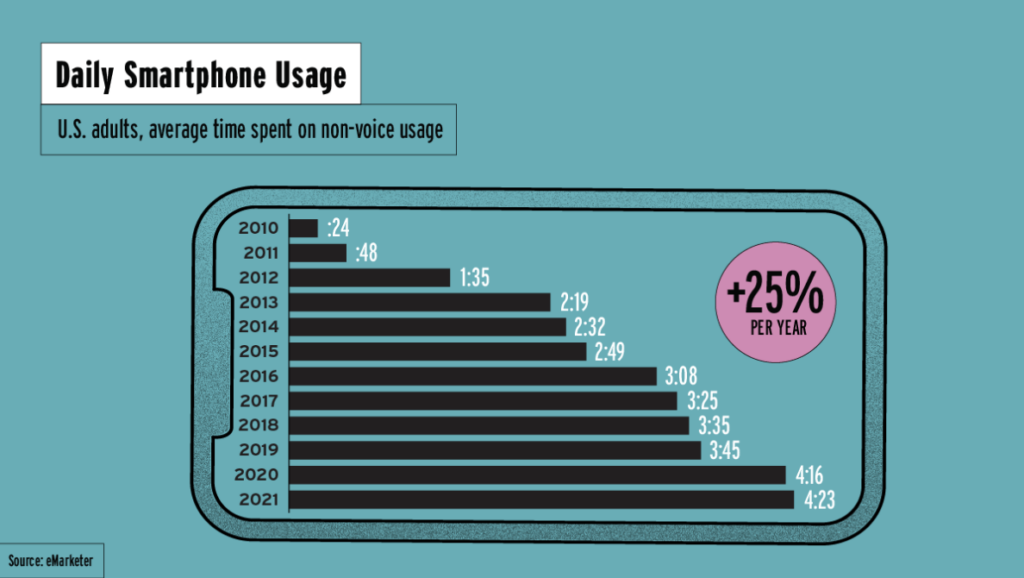

As I waited, I peered over the edge and saw a group of off-duty paramilitary servicemen taking selfies with their backs to the scene. They were capturing the moment using nothing but the cameras on their smartphones. The irony wasn’t lost on me. Here I was, standing high above, with a camera rig that cost as much as a second-hand sedan, waiting for the perfect light as I took great care to keep my own shadow out of the frame. And there they were, recording the same moment with faint regard for the quality of the light or the image itself. Instead, they were letting the chips figure it all out as they strained to document their own presence.

That moment reinforced for me the extent to which the iPhone had changed not just the act of photography, but the very notion of photos. Before other smartphones followed suit, it marked the introduction of a new language and the beginning of a new volume in the annals of visual communication.

From Why the iPhone is today’s Box Brownie camera by Om Malik (whom God Preserve).

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!