Quentin’s got a netbook. So has Dave Winer, who is not impressed by the way Steve Jobs poured cold water on the whole netbook concept. So here’s Dave’s definition of the essence of the netbook.

1. Small size.

2. Low price.

3. Battery life of 4 hours. Battery can be replaced by user. Atom processor seems to be a requirement, those that aren’t Atom aren’t selling (and are apparently being discontinued).

4. Rugged.

5. Built-in wifi, 3 USB ports, SD card reader. It seems it must have 802.11n to be taken seriously.

6. Runs my software.

7. Runs any software I want (no platform vendor to decide what’s appropriate).

8. Competition (users have choice and can switch vendors at any time).

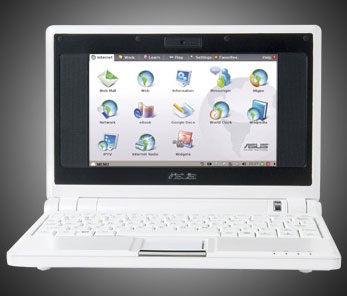

I’ve had an Asus EeePC for just under a year, and have found it impressive and useful. It has some annoyances (battery life not great, forgets WEP passwords when hibernating, undersized trackpad and screen slightly too small for serious browsing). But on the other hand, it came configured with great applications (including Skype and all major flavours of webmail out of the box), is delightfully small and light and fits in anywhere. I took it away on holiday once to see what was lacking — and found that the only thing I really missed was the ability to upload and edit photographs from my digital camera.

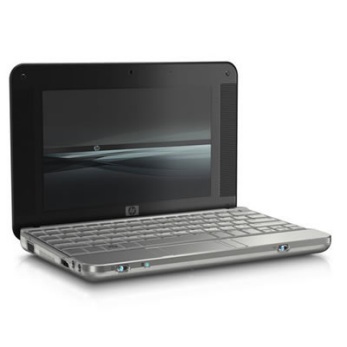

I also bought an HP MiniNote for research purposes — and to see what an established computer manufacturer would do with the netbook idea. The HP machine is beautifully made, has a bigger, nicer screen, a 160GB hard drive and a much better keyboard. But it’s also over-engineered and heavy, has unimpressive battery life and came with the worst Linux distro I’ve ever seen. The machine was effectively unusable until my colleague Michael installed Ubuntu on it.

So… The Netbook genre is still in its early days. The big challenge for the manufacturers is how to resist the temptation of feature-creep. That’s one of the problems of the HP machine — it’s edging back into small laptop territory. And that’s a mistake. The motto for the genre should be KISS — Keep It Simple, Stoopid.

As Dave Winer says, Steve Jobs may be dissing netbooks in public but behind the scenes he’s probably hassling his designers to come up with Apple’s distinctive take on the genre.

LATER: Bang on cue, here’s TechCrunch in speculative form:

This week saw an interesting story come out of the New York Times. The Times reported seeing traffic from an Apple product which has a screen resolution greater than that of an iPhone but less than that of a MacBook. This seems to correlate very well with reports of Apple building something that is akin to a new Newton, although whether it is a bigger iPhone or a MacBook Tablet is still any one’s guess.