My phone beeped at supper time last Tuesday. It was an SMS from one of my sons. “John Updike RIP” was all it said. Then my inbox pinged: a message from an old friend in Holland. Then a tweet from Steven Johnson appeared in my Twitter feed. All over the English-speaking world it was the same. People were registering the loss of a significant presence in their intellectual lives.

My phone beeped at supper time last Tuesday. It was an SMS from one of my sons. “John Updike RIP” was all it said. Then my inbox pinged: a message from an old friend in Holland. Then a tweet from Steven Johnson appeared in my Twitter feed. All over the English-speaking world it was the same. People were registering the loss of a significant presence in their intellectual lives.

“The Updike opus is so vast”, wrote Ian McEwen in the Guardian later in the week,

“so varied and rich, that we will not have its full measure for years to come. We have lived with the expectation of his new novel or story or essay so long, all our lives, that it does not seem possible that this flow of invention should suddenly cease. We are truly bereft, that this reticent, kindly man with the ferocious work ethic and superhuman facility will write for us no more. He was intensely private, learned, generous, courtly, the kind of man who could apologise for replying to one’s letter by return of post because it was the only way he could keep his desk clear.”

The New Yorker, which was, in a way, the fixed point in his life as an essayist, had a nice feature in which writers remembered Updike. Julian Barnes, as usual, was spot on:

“Like many others, I’ve regularly taken Ruskin’s “The Stones of Venice” with me to Venice, and regularly failed to read a word of it there. That reader’s hoped-for matching of text to place frequently disappoints. But once, a dozen or so years ago, it worked miraculously for me. I was setting out on a three-week book tour, crisscrossing America. At Heathrow I bought “Rabbit, Run” and started it on the plane. All reading problems became reading joys for the entire trip. I picked up each succeeding volume in a new city, my bookmarks the stubs of boarding cards. The novels were a distraction from, and a glittering confirmation of, the vast bustling ordinariness of American life. When I managed to escape my professional duties and strolled the urban or suburban streets, I saw Rabbitland everywhere. Even those moments of stunned exhaustion in a new hotel room, when I had the energy only to turn on the television, interacted with my reading, since Updike loves to counterpoint national events (that is, national events as absorbed by Rabbit through television) against the private life of this archetypal twentieth-century American citizen. My book tour finished in Florida – which was perfect, since this was where the fourth volume found “Rabbit at Rest,” in geriatric condo-land. Poor old Rabbit died, the novel ended, and so did my trip. I flew home (and have no memory of what I read on the plane that time) not only convinced that the quartet is the great masterpiece of postwar American fiction but wondering whether I would ever again find such perfect circumstances in which to read it.”

Like most of his readers, I can remember how Updike’s writing fitted into my life. Couples, for example, coincided with my early married life in Cambridge, providing an insight into mores that we knew were — somewhere — in the air. (We used to hear rumours of parties at which — at the end of the evening — people would throw their car keys into a jar and then go home with whoever drew them out. Nobody ever invited us to such functions, so we relied on Updike’s chronicle of suburban adultery for circumstantial detail.)

Years later, in preparation for my first trip to the US, I embarked — rather as Julian Barnes had — on the Rabbit books, and found myself hooked. And enlightened. James Joyce used to say that if Dublin were destroyed, the city could be rebuilt by consulting the pages of Ulysses. My feeling about the Rabbit books was that they fulfilled much the same function for 1950s – 1980s small-town America. Indeed I remember once coming across a PhD thesis which examined the accuracy of Updike’s portrayal of social changes in suburban America and found it to be very perceptive. His decision for example, to make Harry Angstrom a used-car dealer was particularly astute: automobiles are pretty central to an understanding of American culture, and Updike spotted the significance of Toyota long before Detroit woke up to the danger that the Japanese car manufacturers represented. In one of the features marking his death, the Guardian ran a very nice audio interview in which he talks about the Rabbit series.

In other small ways, his experiences resonated with mine. I was intrigued to discover from his autobiography, for example, that his life had been shaped in some small but not insignificant way by the fact that he suffered, as I do, from psoriasis. And he wrote beautifully about golf, the only game I have ever loved.

I met him once. It must have been in the 1980s, on a wet winter’s morning in Cambridge. He was neatly attired in classic Wasp gear: button-down shirt and tie, subtle tweed jacket, grey trousers, nicely-polished shoes. He had come to Heffers to sign books, and for some reason very few people had turned up. So he sat at a table in the mezzanine which is now used for DVDs, courteously signed the odd book for passing customers, and chatted to me. I had my Leica with me and took some very nice pictures, including a striking one of him smiling, over his spectacles, at a customer. But the print and the negative are locked away somewhere in an attic and I haven’t been able to summon up the courage to go rummaging for them. Sigh.

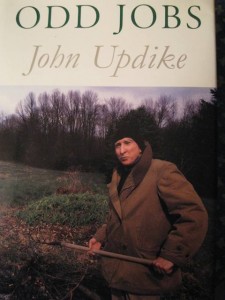

For anyone who aspires — and struggles — to write, Updike was an exasperating phenomenon: unbelievably prolific, and yet never shoddy. When the news came of his death I pulled down my copy of Odd Jobs (see picture) — a collection of reviews and essays written over a few years in the interstices of writing a series of major novels. It runs to 914 pages! But it’s the title that really rankles, implying as it does that this is stuff he did before breakfast.

“He said he had four studies in his house”, wrote Martin Amis in Wednesday’s Guardian,

“so we can imagine him writing a poem in one of his studies before breakfast, then in the next study writing a hundred pages of a novel, then in the afternoon he writes a long and brilliant essay for the New Yorker, and then in the fourth study he blurts out a couple of poems. John Updike must have been possessed of a purer energy than any writer since DH Lawrence.

I’ve seen it suggested that such prodigies suffer from an enviable condition called ‘pressure on the cortex’. It’s as if they have within them an underground spring which is always on the point of eruption.”

I benefited from being drenched by that spring. Not many writers have such a capacity to get under one’s skin and into one’s consciousness. “Several times a day”, wrote Amis,

you turn to him, as you will now to his ghost, and say to yourself ‘How would Updike have done it?’

You do indeed. May he rest in peace.