It’s harvest day on the farm next to where we live. By the standards of my (Irish) childhood, it’s an enormous farm — maybe 300 acres, but by East Anglian standards it’s quite small. It’s owned by the University of Cambridge and our neighbour is therefore a tenant farmer. A century ago it would have employed maybe a dozen labourers, plus the farmer’s able-bodied sons. Now it employs precisely one person — the farmer himself.

All of this is possible because he now grows only cereals, and because of mechanisation. Up to this year, he’s done the harvesting himself, but his combine harvester is now so old, he tells me, that he can only get spares from the scrap dealer. So this year he’s got contractors in to do it, and this is the day they’ve chosen.

They’ve been at it since before dawn. It’s now dark and I’m sitting in the garden listening to the roar of enormous tractors pulling large trailers which, at about ten-minute intervals emerge from the fields loaded with grain. They go back and forth to the combine, load up with the grain that’s been cut and threshed in the intervening period, tip it out and then return to the fields. The house shakes as they thunder past.

Suddenly I’m transported back to my childhood, over half a century ago. We’re in Connemara, where my paternal grandparents were peasant farmers. They owned no machinery but did have a donkey and a cow. They lived in a classic Irish thatched cottage. The heart of the house was a large high-ceilinged kitchen with an open fire which burned turf (i.e. peat). At each gable end of the house there were a few tiny rooms – one a parlour which was never used, as far as I remember, except for laying out the corpse after a death or giving tea to the parish priest on his occasional, ceremonial visits. The other rooms were bedrooms, each with a brass bedstead, a patchwork quilt and a stand with a porcelain basin and a jug.

The kitchen was pretty dark, even in the daytime. On one side there was a door which led out into the yard, where chickens scratched and cackled. (They would have come into the stone-flagged kitchen if there hadn’t been a half-door.) On the other side of the room were two small windows, each with four quadrants of glass. There was no electricity and no running water.

It was the first time I remember staying there. My brother and I had come on a visit with my father — who had escaped from his background because a teacher had spotted his potential and kept him on at school after the statutory leaving age of 14. My mother was staying with my baby sister at her parents’ house, many miles away in Mayo, in the more salubrious setting of a prosperous merchant household.

We were deeply in awe of Da’s parents. They were silent, kindly but stern and spoke only Irish. Grandad (called Daidó) wore classic bainín clothes and hobnail boots; Grandma (called Mamó) wore a shawl when she went out. She also took snuff, which amazed, fascinated and slightly repelled us. They took the view that children should be seen and not heard, so we were correspondingly visible but taciturn. There were no toys of any description in the house.

The day I’m thinking of was in high summer. Daidó owned a small number of fields, most of which were rocky beyond belief. (Not for nothing had Cromwell given my forebears the option of “To Hell or to Connacht”.) But on the road up to the bog Daidó had three fields which had been largely cleared of rocks and were essentially smallish meadows. My father and he disappeared early in the morning, just after dawn. At about 10.30 in the morning, my brother and I were given large jugs of buttermilk covered with muslin, together with loaves of sodabread, and told to bring them up to the fields. When we got there we found a large group of men, maybe a dozen in all, moving through the fields with scythes, cutting the grass. They stopped when they saw us coming, gathered round and drank and ate without saying much. To us they said absolutely nothing.

We returned to the cottage. There was absolutely nothing to do. Mamó busied herself in various farmyard chores. My brother and I mooched about the duckpond in the centre of the cluster of houses which made up the tiny hamlet. The entire settlement was deathly quiet, baking in the sunshine. The day seemed interminable. Evening came and, to our surprise, we were not sent off to bed. At about 10pm we watched as Mamó scrubbed a huge pile of potatoes and put them into a large black pot which she suspended over the open fire. She then lit the oil lamps. When the potatoes were cooked, she turned them out into a huge basket, where they lay steaming. She then fetched a block of salted butter and jugs of buttermilk from the little lean-to dairy outside the house, and sat by the fire taking snuff.

In that part of the west of Ireland, it doesn’t get really dark until nearly 11pm in June. But as the light was fading, the door of the cottage opened and in filed the group of men who had been working with Da and Daidó in the fields. They said very little, just sat around the walls of the kitchen on chairs. Each was given a plate with floury potatoes and glistening knobs of melting butter. And a cup of buttermilk. They ate quietly. There was an occasional murmur of conversation, but what I remember most was the quiet munching of tired men. Then, without saying much, they got up and walked out into the glow of a midsummer night.

This was my first glimpse of the meitheal system, in which peasant farmers with no access to machinery would combine to help each other with the harvest. Tomorrow my grandfather would go to one of their fields and return the compliment. And we would return to the world of mains electricity and running water.

Viewed from the perspective of this evening, when the rumble of heavily-laden tractors still rattles our windows, and one man can run a 300-acre farm, this memory seems as distant as the middle ages. And yet it’s a vivid recollection of a lived experience. This is what the ‘Celtic tiger’ was like within living memory — a country as poor and as backward as parts of Albania are today.

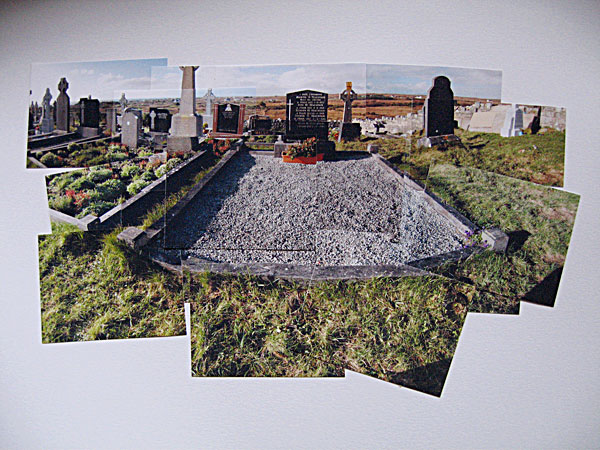

Many years after that first visit to my grandparents, Sue and I visited the graveyard where they are buried. (They died in the 1970s within 24 hours of one another, both aged 94.) It’s a lovely, peaceful place which looks out over Galway Bay and the Aran islands. But it’s also contains a sharp reminder of what progress means: the family plot shows that in the space of a single terrible year Mamó and Daideó lost three of their nine children to those infectious diseases which once cut a swathe through every family in rural Ireland. Two of the children died within a week of one another. Modernity may have its discontents. But it also has its consolations.