Neat, eh?

So which was the bigger scam — balloon boy or the Collateralised Debt fraud?

Terrific NYT column by Frank Rich comparing the “balloon boy” scam with those perpetrated by Bush/Cheney in invading Iraq and by Wall Street in fuelling the banking collapse, and putting things nicely in context. Excerpts:

Next to the other hoaxes and fantasies that have been abetted by the news media in recent years, both the “balloon boy” and Chamber of Commerce ruses are benign. The Colorado balloon may have led to the rerouting of flights and the wasteful deployment of law enforcement resources. But at least it didn’t lead the country into fiasco the way George W. Bush’s flyboy spectacle on an aircraft carrier helped beguile most of the Beltway press and too much of the public into believing that the mission had been accomplished in Iraq. The Chamber of Commerce stunt was a blip of a business news hoax next to the constant parade of carnival barkers who flogged empty stocks on cable during the speculative Wall Street orgies of the dot-com and housing booms.

[…]

Richard Heene [the father in the “balloon boy” incident] is the inevitable product of this reigning culture, where “news,” “reality” television and reality itself are hopelessly scrambled and the warp-speed imperatives of cable-Internet competition allow no time for fact checking. Norman Lear, about the only prominent American to express any empathy for little Falcon’s father, vented on The Huffington Post, calling out CNN, MSNBC, Fox, NBC, ABC and CBS alike for their role in “creating a climate that mistakes entertainment for news.” This climate, he argued, “all but seduces a Richard and Mayumi Heene into believing they are — even if what they dream up to qualify is a hoax — entitled to their 15 minutes.”

[…]

If Heene’s balloon was empty, so were the toxic financial instruments, inflated by the thin air of unsupported debt, that cratered the economy he inhabits. The press hyped both scams, and the public eagerly bought both. But between the bogus balloon and the banks’ bubble, there’s no contest as to which did the most damage to the country. The ultimate joke is that Heene, unlike the reckless gamblers at the top of Citigroup and A.I.G., may be the one with a serious shot at ending up behind bars.

Great stuff. Worth reading in full.

Full disclosure

This lovely photograph from the terrific Red Mum photoblog reminded me of a shameful episode from my childhood. Note the qualifications of the pharmacist on the shop-front, which signify that J.H. Bowden is a Member of the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (MPSI). When we were kids, we had a more scabrous interpretation of the letters, and we would sometimes go into the local pharmacist’s and shout “Monkey’s Piss Sold Inside” before scarpering, closely pursued by a stout, irate proprietor.

Disgraceful, I know. I should be ashamed of myself. Well, of my younger self, anyway.

UPDATE: Red Mum has moved to WordPress. New blog here.

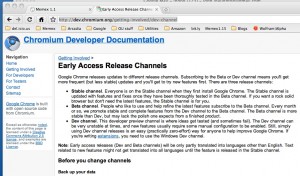

Google Chrome for Mac OS X

Following a tweet from Stephen Fry (who else?) saying “now running Chrome on OS X” I went looking and found (and downloaded) the build created by Codeweavers. Now running it — though not as a default browser because it’s not a stable version. The relevant Google page is here.

The myth of teenage omnipotence

This morning’s Observer column.

THE OLD SAYING that “if you’re not thoroughly confused you don’t fully understand the situation” applies with a vengeance to our new media ecosystem. Take the strange case of teenagers, whose brains are being scrambled and rewired by nature to make them fit for adult life. Until the 1960s, “teens” as they are called in the US barely existed as an interesting social category. Like sex in Philip Larkin’s poem, Annus Mirabilis, one might say they were “invented in nineteen sixty-three/… Between the end of the Chatterley ban/And the Beatles’ first LP”.

Then they acquired spending power and became interesting to retailers and advertisers – and therefore to the mass media – to the point where our society is now obsessed with them. This obsession is particularly neurotic whenever cyberspace is mentioned, and leads adults to project on to the younger generation all kinds of fears and fantasies…

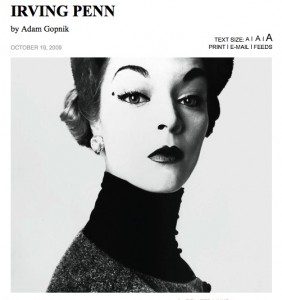

Ingres with a Leica

The New Yorker carried an elegant tribute to Irving Penn by Adam Gopnik.

In the postwar years, America was unduly blessed by its art dealers, who offered an open door to the avant-garde, and by its fashion magazines, in which a handful of photographers managed to turn fashion pictures into another kind of high art. Chief among them was Irving Penn, who died last week, at the age of ninety-two. There are many instinctive romantics among popular artists, the Gershwins and the Chaplins who, through force of spirit and originality of style, take by storm the balcony and the boxes alike. Penn was something rarer, an instinctive popular classicist, with a magical gift for visual rhythm, for making something insignificant—a pattern of cigarettes and ashes, each ash miraculously in its one best place—look as formally inevitable as an eighteenthcentury still-life. If Richard Avedon, his great rival and competitor, was a snapshot Delacroix, all fire and figures, Penn was Ingres with a Leica, all ravishing edges and perfect composition and a quality of deep color that was the envy of every other photographer.

Universal phone charger approved

From BBC NEWS.

A new mobile phone charger that will work with any handset has been approved by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a United Nations body.

Industry body the GSMA predicts that 51,000 tonnes of redundant chargers are generated each year.

Currently most chargers are product or brand specific, so people tend to change them when they upgrade to a new phone.

However, the new energy-efficient chargers can be kept for much longer.

The GSMA also estimates that they will reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions by 13.6m tonnes.

About time too. Now for digital camera chargers…

Thanks to James Miller for spotting it.

Promises, promises

The launch of Windows 7 required an update of the “I’m a Mac…” ads. Here’s the first one.

Technology as jewellery

The culture crosser

Lisa Jardine lecturing against a backdrop of (I think) Feliks Topolski’s portrait of C.P. Snow

I went to the C.P. Snow Lecture in Christ’s last Wednesday with fairly low expectations generated by the title “The Two Cultures Revisited”. What more is there to be said about the famous Rede lecture, delivered 50 years ago just down the road in the Senate House? Were we going to be treated to yet another rehash of the row between Snow and another Cambridge figure of the time, F.R. Leavis? As it turned out, I needn’t have worried: the lecturer was Lisa Jardine, who is feisty, clever, courageous, multi-disciplinary and stimulating — and now Chair of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. It’s a racing certainty that she will eventually wind up as a Dame of the non-pantomime variety.

The hall was packed with the Cambridge establishment. George Steiner was there and Martin Rees and a host of other grandees. Lisa was introduced by Frank Kelly, a near-contemporary of mine who is now Master of Christ’s and has done great work in the area of self-managed systems. He is also, as it happens, an experienced pacer of those Whitehall walkways memorably described by Snow as “corridors of power”. After a hesitant start she launched into an interesting take on the ‘two Cultures’ lecture in which she argued that while most people have regarded the Rede lecture as the starting point for a debate that has raged ever since, Snow himself saw it as a culminating formulation of a problem that had been bothering him for years, namely the hideously inadequate way our society goes about making decisions which require informed scientific advice.

With the benefit of hindsight, Jardine claimed, we can see how Snow’s thinking evolved. But he didn’t really expound it clearly until two years later, when he gave the Godkin lectures at Harvard which were eventually published under the title Science and Government. The inescapable logic of her argument was that if you want to appreciate the ‘Two Cultures’ lecture, then you have to read the Godkin lectures first.

As it happens, this isn’t an entirely original thought — it was the basis of an interesting essay last April by Chris Mooney and Sheril Kirshenbaum which was published in the magazine of the New York Academy of Sciences. “Snow cared a great deal about breakdowns between scientists and writers”, they wrote,

“but the reasons he cared are what ought to most concern us, because they still resonate across the 50-year remove that separates us from Snow’s immediate circumstances. Above all, Snow feared a world in which science could grow divorced from politics and culture. Science, he recognized, was becoming too powerful and too important; a society living disconnected from it couldn’t be healthy. You had cause to worry about that society’s future— about its handling of the future.

For this lament about two estranged cultures came from a man who had not only studied physics and written novels, but who had spent much of his life, including the terrifying period of World War II, working to ensure that the British government received the best scientific advice possible. That included the secret wartime recruitment of physicists and other scientists to work on weapons and defenses, activities which put Snow high up on the Gestapo’s Black List. So, no: Snow’s words weren’t merely about communication breakdowns between humanists and scientists. They were considerably more ambitious than that—and considerably more urgent, and poignant, and pained.”

Mooney and Kirschenbaum see Snow as an early theorist on “a critical modern problem: How can we best translate highly complex information, stored in the minds of often eccentric (if well meaning) scientists, into the process of political decision making at all levels and in all aspects of government, from military to medical?” Like Jardine, they see the Godkin lectures as the key to understanding what he was trying to get at in the Rede lecture.

“Snow illustrated the same dilemma through the example of radar. He argued that if a small group of British government science advisers, operating in conditions of high wartime secrecy, had not spearheaded the development and deployment of this technology in close conjunction with the Air Ministry, the pivotal 1940 Battle of Britain—fought in the skies over his nation—would have gone very differently. And Snow went further, identifying a bad guy in the story: Winston Churchill’s science adviser and ally F.A. Lindemann, who Snow described as having succumbed to the “euphoria of gadgets.” Rather than recognizing radar as the only hope to bolster British air defenses, Lindemann favored the fantastical idea of dropping parachute bombs and mines in front of enemy aircraft, and tried (unsuccessfully) to derail the other, pro-radar science advisers. Churchill’s rise to power was an extremely good thing for Britain and the world, but as Snow noted, it’s also fortunate that the radar decision came about before Churchill could empower Lindemann as his science czar.

So no wonder Snow opposed any force that might blunt the beneficial influence of science upon high-level decision-making. That force might be a “solitary scientific overlord”—Snow’s term for Lindemann—or it might be something more nebulous and diffuse, such as an overarching culture that disregards science on anything but the most superficial of levels, and so fails to comprehend how the advancement of knowledge and the progress of technology simultaneously threaten us and yet also offer great hope.”

To this, Jardine added another case-study: the conflict between Tizard and Lindemann about the merits of strategic bombing. In this case, Tizard lost the battle for Churchill’s ear, and the Allies embarked on a bombing campaign that killed at least half a million German civilians and 160,000 Allied aircrew. In retrospect, the strategic bombing campaign looks awfully like a war crime, and of course the fire-bombing of Dresden certainly was such a crime. To Snow — and to any sentient being — the story of the policy debate behind the campaign highlights the importance of having a political culture which can attend intelligently to scientific advice.

As befits a cultural historian, Jardine added her own twist to the story, by delving into the ideological underpinnings of the 1951 ‘Festival of Britain’, which was ostensibly a government-sponsored device for cheering up a public exhausted by war with a celebration of British scientific and manufacturing ingenuity, but which managed to avoid almost any reference to military hardware and conspiciously ignored the most compelling example of what happens when you combine scientific IQ with massive government resources, namely the atomic bombs which vapourised the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She showed some fascinating illustrations from the catalogues produced for the Festival (purchased in mint condition on ABE Books, btw), and closed with some scarifying examples of how scientifically — and mathematically — illiterate our mass media (and the public) have become. The Authority, for example, publishes statistics about the success rate of In-vitro Fertilisation (IVF) treatments — which is about 30%. “That means”, she said, “that if you go to an IVF clinic you have a one in three chance of conceiving”. But it seems that most people are exceedingly pissed off if they come out of an IVF clinic without a baby.

As for me, I went to the lecture thinking that I had a 30% chance of being surprised. And discovered that I had been 100% stimulated.