Trussonomics

Seen on the side of a large building in London yesterday. I was reminded of a conversation between two women I overheard on a Dublin bus many years ago. They were discussing their ‘useless’ sons, both of whom were apparently incapable of getting their respective acts together. One woman complained bitterly about her boy Seamus who “just lies about all day watching TV”. Her companion said, brightly, “Why doesn’t he go into demolition? I hear there’s a great future in that.”

There is. All he needs to do is join the Tory party.

Quote of the Day

”Far too noisy, my dear Mozart. Far too many notes.”

- Archduke Ferdinand, after the first performance of The Marriage of Figaro

See below…

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Renée Fleming | Porgi Amor | The Marriage of Figaro | Chicago, 1998 | Conducted by Zubin Mehta

Link

Long Read of the Day

What Liz Truss Proved

Astute analysis by Francisco Toro pointing out that the Truss omnishambles in the UK and the Trump catastrophe in the US have a common root cause — the thoughtless ‘democratisation’ of the process of choosing political leaders in Democrat, Republican, Conservative and Labour parties.

Until 1998, Conservative members of parliament (MPs) had the job of choosing their party leader. That leader would become head of government if the party could command a majority in the House of Commons. After 1998, however, the rules changed: henceforth Conservative MPs would “thin the herd” of leadership hopefuls through successive rounds of balloting, then leave the choice between the final two to the members.

What could possibly go wrong?

A lot, it turns out. Political scientists know that weakening party officials can introduce all kinds of dysfunction into a democracy. Britain’s recent history bears that out in great detail…

Do read on.

Books, etc.

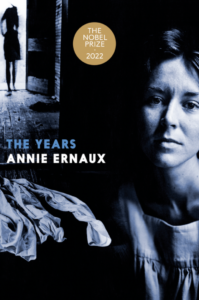

When I learned that Annie Ernaux had won this year’s Nobel Prize for literature my first, embarrassed, thought was that I’d never heard of her. On the other hand, that was hardly surprising since she wrote (and was published) only in French, a language I don’t read. But then I discovered that her 2008 magnum opus, The Years, had been translated and so I bought it and was, well, transfixed.

It’s a kind of autobiography, but one in which the author never once uses the pronoun “I”. It’s always “she” or “her”. Ernaux has effectively invented a new genre — an intimate portrait of an entire generation — hers — from 1940 to 2006. She calls it autosociobiography. And although she’s a bit older than me, her brisk, unsentimental, clear-eyed evocation of experiences, social and political change, marriage, children, middle-class ennui and all the other things that go to make up a life resonate with the contemporary reader. The book, one reviewer concluded, “is placed somewhere on the edges of literature, history, and sociology. It moves in fragments, from personal to common, from exceptional to ordinary and vice versa”.

Sometimes, it reads like an endless stream of consciousness — but a capacious consciousness that notices everything, from the absurdities of French presidents to the smell of menstrual blood, from the strange way rebellious adolescents morph into responsible young parents with mortgages and feelings of psychic imprisonment, and then into divorcees trying to explore new-found liberties while at the same time coming to terms with mortality. And so on.

As the stream flows, we find Ernaux continually returning to thinking about the book she feels impelled to write.

She would like to assemble these multiple images of herself , separate and discordant, thread them together with the story of her existence, starting with her birth during World War II up until the present day. Therefore, an existence that is singular but also merged with the movements of a generation. Each time she begins, she meets the same obstacles: how to represent the passage of historical time, the changing of things, ideas, and manners, and the private life of this woman? How to make the fresco of forty-five years coincide with the search for a self outside of History, the self of suspended moments transformed into the poems she wrote at twenty (‘Solitude’, etc.)? Her main concern is the choice between ‘ I ’ and ‘ she ’.

In the end, she sure solved that problem. And this reader, for one, couldn’t put her book down.

But don’t take my word for it. There are interesting reviews here, here and here.

My commonplace booklet

Why to avoid ‘very’ in English grammar

Nice Opinion piece in The Washington Post.

One must draw the line somewhere. I recommend striking out “actually” at every opportunity, unless it’s in a discussion of the movie “Love Actually,” in which case we might want to focus on the title’s confounding commalessness. Similarly, though I would never fault the supreme lyricist Johnny Mercer for the gorgeous “You’re much too much / And just too very very,” I am on constant alert for “very,” always looking for the chance to dispose of it. I’d encourage you to do the same.

For one thing, “very” is a fraud, masquerading as a strengthener when it merely wheedles and pleads. To call someone “brilliant” is to make a bold assertion; to call someone “very brilliant” attempts to persuade others of something one appears not to truly believe. Moreover, it’s a dull adverb and encourages duller adjectives. What, after all, is “very hungry” compared with “ravenous”? What’s “very sad” up against “despondent”? Who’d want to be “very strong” when you might be “herculean”?

It’s by Benjamin Dreyer, who is Random House’s executive managing editor and copy chief. He’s also the author of Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style which, on closer inspection, it not at all as pompous as its title. In fact, it’s rather nicely written — though he would immediately put his blue pencil through that ‘rather’.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!