Seen in a car dealership while waiting for service. Flickr version here.

Quote of the Day

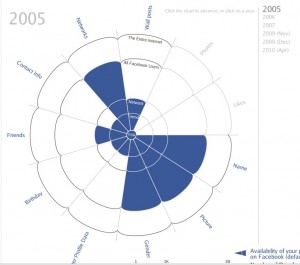

Facebook’s privacy problem

If you want to understand why people are concerned about the erosion of privacy in Facebook, then have a look at Matt McKeon’s terrific animation of what’s being going on since 2005.

Democracy, huh?

While we’ve been celebrating the peaceful transfer of power in Britain, over in Washington the Obama administration has been stroking Hamid Karzai, the corrupt, incompetent ‘president’ of Afghanistan who — among other things — stole the last presidential election and refuses to concede control over the electoral monitoring process for the next. When Obama first visited Kabul a few months ago, he made clear his distaste for this criminal. But it now seems that the exigencies of US military operations in Afghanistan has required a change of heart. All of which reminds me of Barbara Tuchman’s marvellous book about imperial military adventures. Her essay on Vietnam, for example, reminds us that the weaker the corrupt, incompetent Saigon government became, the greater the leverage it exerted on the Administration in Washington. History repeats itself, as usual.

Inside the bunker

The Guardian had a photographer inside No 10 Downing Street during the last hours of Gordon Brown’s premiership. He’s produced a memorable slideshow.

The last word…

… from Marina Hype, er Hyde*. Lovely Guardian piece. She’s particularly good on the increasingly-bizarre media circus that developed as the coalition negotiations dragged on.

To say that by the end of this saga the media had begun to eat itself wouldn’t begin to cover the cannibalistic orgy that has been raging in Westminster. News channel helicopters drowned out their own ground-level broadcasts, ably assisted by megaphone-wielding members of the public who chanted things like “Sack Kay Burley!” Ever more outlandishly repellent pundits were exhumed. Kenneth Baker … oof, mine eyes! For political junkies it had the flavour of Pokemon – gotta catch’em all.

For less insane members of the public, this week has presumably acted as a sort of politics aversion therapy, ensuring that every time someone even says the words “strong and stable government”, intense feelings of nausea and images of Alastair Campbell will flood their brain.

The geographically tiny village of Westminster has resembled nothing so much as a meth-assisted version of Camberwick Green, with the Sauron-like capabilities of news channels allowing viewers to follow dramatis personae round this weirdo toytown. There were the Lib Dems leaving their headquarters; there they were walking to the Cabinet Office; there they were a few minutes later arriving. And oh look — there’s Windy Miller talking to Kay Burley on College Green.

Unbelievably – although not really within the context of the past few days – a giant rainbow appeared over the palace just as Cameron’s car swept in. In the coming days, do expect unicorns to follow.

*Footnote: Thanks to the eagle-eyed Hugh Taylor for spotting the typo.

The big question…

Touchy subjects

I went to see my GP on Monday. Upon arrival, I noticed that there was a touchscreen monitor on the reception desk. “Touch here to arrive for your appointment” it said. “Arrive???” Resisting the temptation to point out the grammatical absurdity of the invitation to the receptionist, I duly ‘touched’ the screen and was invited to enter my date of birth, after which a welcome message flashed up.

Sitting in the waiting room, I fell to reflecting on this. During the swine-flu panic, we were constantly exhorted to avoid touching strange doorknobs etc. And yet here we are in a GP’s surgery merrily placing our various germs on a common screen. Hmmm…

Later, in one of those lovely serendipitous coincidences, this message from a long-term correspondent popped into my inbox:

My local surgery is very progressive. On the information side, their mail/email handling of repeat prescriptions is first class.

Recently however they have introduced, as an alternative, a touch screen check in system…. (an NHS standard ?).

You may check in for a scheduled appointment by using by the touch screen. First, however you need to wipe your hands with antiseptic gel. There is a large notice telling you do so. Standing next door to this facility whilest collecting my repeat prescription, I noted that out of 7 users, 3 omitted to clean their hands…

I still use the ‘person to person confrontational’ check in. As a regular, the receptionists know me and greet me and we exchange pleasantries in a friendly fashion. As far as I know we don’t infect each other. She often gives me additional information unknown to the automated system. e.g. which end of the reception area to sit for my blood test call.

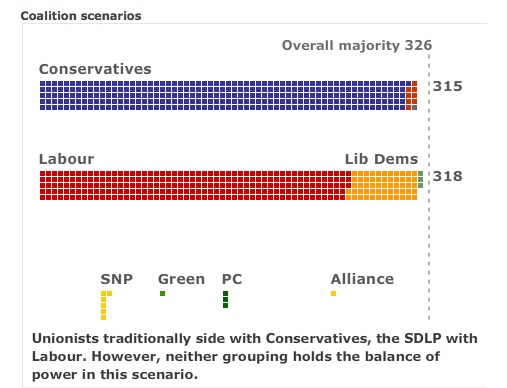

Political arithmetic: the hard facts

From the BBC web site. Suggests that the so-called “Rainbow coalition” is implausible. The Scots and Welsh Nats have explicitly stated that they would not support public-sector cuts in their territories. And of course many Labour MPs cannot abide the SNP.