Terrific interview which provides a really good explanation of neutrality and how it should apply in the wireless world — and how Google is beginning to think like a Telco. Suddenly made me wonder if Google was more badly burnt by its failure to run a phone shop than we had believed. I’m currently reading Wu’s new book, which is likewise very sobering. Wonderful quote: “The only time that governments do the right thing is when the people are paying attention”.

Happy Birthday ORG!

The Open Rights Group is 5 today!

How golf ought to be

Having been brought up in Ireland, I love links (i.e. sandy, windswept, seaside) golf courses. I particularly like the way these courses can humble even golf’s most prominent billionaires whenever a major championship is held on one.

This is the view from the fifth tee at Sheringham, a lovely links course in North Norfolk.

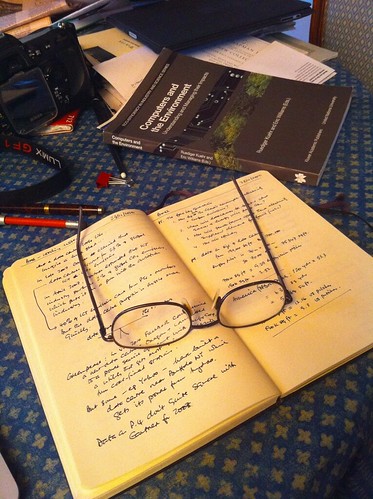

Workspace

Sometimes, you just can’t beat an olde-worlde paper notebook. Highly portable, great screen resolution, excellent, intuitive user interface and infinite battery life.

Only problem: it’s hard to back up. On the other hand, it’ll still be readable in 200 years. Which is more than can be said for any of my digital data.

Where the computer went

This Google video provides a company-approved tour of one of its data centres (aka server farms). I’m writing about the environmental impact of cloud computing at the moment, and rediscovered it when going through the research files for my book. It provides an interesting glimpse of the heavy engineering that lies behind cloud computing.

Toolbox

So were the Israelis behind the Stuxnet worm?

According to the NYTimes, it’s beginning to look that way.

Experts dissecting the computer worm suspected of being aimed at Iran’s nuclear program have determined that it was precisely calibrated in a way that could send nuclear centrifuges wildly out of control.

Their conclusion, while not definitive, begins to clear some of the fog around the Stuxnet worm, a malicious program detected earlier this year on computers, primarily in Iran but also India, Indonesia and other countries.

The paternity of the worm is still in dispute, but in recent weeks officials from Israel have broken into wide smiles when asked whether Israel was behind the attack, or knew who was. American officials have suggested it originated abroad.

The new forensic work narrows the range of targets and deciphers the worm’s plan of attack. Computer analysts say Stuxnet does its damage by making quick changes in the rotational speed of motors, shifting them rapidly up and down.

Changing the speed “sabotages the normal operation of the industrial control process,” Eric Chien, a researcher at the computer security company Symantec, wrote in a blog post.

Those fluctuations, nuclear analysts said in response to the report, are a recipe for disaster among the thousands of centrifuges spinning in Iran to enrich uranium, which can fuel reactors or bombs. Rapid changes can cause them to blow apart. Reports issued by international inspectors reveal that Iran has experienced many problems keeping its centrifuges running, with hundreds removed from active service since summer 2009…

More detail here.

“Balliol College, Cambridge”

This is the old Spillers flour mill next to Cambridge station. The buildings around it have been razed for housing ‘development’ — ie hideous apartment blocks. But the mill itself is a listed building & so the developers have to keep it. The caption comes from a speech Ronald Knox made at the Cambridge Union, when he referred to the building as “Balliol College, Cambridge” — a jibe at Oxford’s most intellectually distinguished – but architecturally jumbled – college.

Something to keep you awake at night

Ever since Obama won the election I’ve had an uneasy feeling that Sarah Palin is being underestimated by the US media and political establishments. Frank Rich has come to the same conclusion. “Logic”, he writes,

doesn’t apply to Palin. What might bring down other politicians only seems to make her stronger: the malapropisms and gaffes, the cut-and-run half-term governorship, family scandals, shameless lying and rapacious self-merchandising. In an angry time when America’s experts and elites all seem to have failed, her amateurism and liabilities are badges of honor. She has turned fallibility into a formula for success.

Republican leaders who want to stop her, and they are legion, are utterly baffled about how to do so. Democrats, who gloat that she’s the Republicans’ problem, may be humoring themselves. When Palin told Barbara Walters last week that she believed she could beat Barack Obama in 2012, it wasn’t an idle boast. Should Michael Bloomberg decide to spend billions on a quixotic run as a third-party spoiler, all bets on Obama are off…

The boys from the IMF

The only Irish novelist with the range to encompass what has happened to Ireland in my lifetime is Colm Toibin, and so I live in hope that one day we will get a blockbuster novel from him about the Republic that wasn’t. In the meantime, his reflections on the current crisis are interesting. He begins by revealing that he got to know some of the IMF guys who came to sort our Argentina after its economic collapse, and in the process came to understand how they think.

I remembered my American friends this week as news came that a delegation from the EU and the IMF were to arrive in Dublin on Thursday. I think I have an idea how dedicated and serious-minded these fellows would be, especially on weekdays, and how little interest they might have in Irish history, Irish pride, Irish sovereignty or even Irish doublespeak. They like to get the job done and then get home.

On the night before these figure-crunchers arrived in the city, I watched a discussion programme on Irish television in which commentators, people younger than me, invoked the dead heroes who had fought for an independent Ireland, naming some of them, including patriots from the 18th century, and wondering how they would feel now were they to find out about the shame we Irish felt.

We had fought so hard for our freedom, they said, and now, with the arrival in Merrion Street, where the government is housed, of besuited stone-faced economists with German and Scandinavian names and number-crunching knuckles, we had betrayed our dead. Patrick Pearse eat your heart out, the Germans have arrived.

I hadn’t known that Toibin comes from a Republican background. His grandfather fought in the 1916 rebellion and was imprisoned afterwards. “I was brought up”, he recalls, “in the proud memory of his bravery. My uncle and my father worked all their lives for the Fianna Fáil party which has run Ireland most of the time since 1932 and which is in power now. I have never ceased to believe in their patriotism and idealism”.

But he puts his finger on what has always been wrong with our little Statelet:

The problem is not merely that there is no blueprint in Ireland now, no agenda, for how this might be done. The problem is also that it wasn’t there before the Celtic Tiger either, nor during its heady reign. In areas which really matter, such as health and education, Ireland has, since independence, been deeply divided.

There are two health systems here, for example. One is for middle-class people who pay health insurance and the other for those who can’t afford to pay. There are short waiting lists for one, and long waiting lists for the other. Often, both see the same doctors, who treat the first group in private hospitals, or private rooms in public hospitals, and the second group in public hospitals.

Everyone here knows that the difference can be a matter of life and death. Some of the doctors make a fortune. There has been no serious effort to reform this, but many efforts instead to copper-fasten it. This is one example of what sovereignty has done to us.

As for Irish “shame” about having to be rescued by “the Germans”, well, that’s also a bit rich coming from a country that has so manifestly proved unable to govern itself.

The more I found out about contemporary Germany, for example, and the more I travelled there, the more I came to admire it and the more I came to hope that some of its best qualities could come to influence and affect Ireland.

Thus when the Irish Times on Thursday mentioned “the German chancellor” I did not automatically feel that this person was in some way a malignant force in the world. Instead, I saw someone rational and prudent, sensible and deeply intelligent.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this in the last week. In the late 1970s I spent a year working in the Netherlands and it changed my life, because it gave me an insight into what a well-governed society could be like. Holland was devastated after the war, with its population starving and totally dependent on foreign aid. And yet out of those ruins the Dutch built a prosperous, liberal, humane democracy. So did the Germans, labouring under an even bigger psychic burden. What these societies did demonstrates what can be done with political will and intelligent outside assistance. That’s what Ireland needs to do now. And if the IMF and EU boys can get that process started, then more power to their elbows.