Reflections in my sitting room.

Boom, bust and Ballybofey

Classic boom-‘n-bust story by the excellent Lisa O’Carroll in the Guardian.

It was the story of Ireland’s boom and bust in a nutshell: a newly built apartment block near the windswept coast of far-flung Donegal, once valued at €9.5m, was selling for €500,000 (£425,000).

But now, it seems, it’s not even worth that. Navenny Place, a 47-apartment complex, was withdrawn from auction this week after just one token bid of €5,000 – and that was after the auctioneer reduced the starting price to €300,000, or €6,383 per flat.

The apartments are situated on the edge of Ballybofey, a pretty town in the heart of Donegal, and are described by the estate agent as “architecturally superior”, akin “to the type of property found in London’s Docklands”.

Hmmm… Only a couple of things wrong with the story. Firstly, Ballybofey is quite a long way from the coast. And only an estate agent would describe Ballybofey as “pretty”. I’ve always thought it was a pretty drab little place whose main claim to fame was that it housed Donegal’s biggest department store.

On the doorstep

Walking through town early one morning I saw these on a doorstep and wondered about the story that lay behind them.

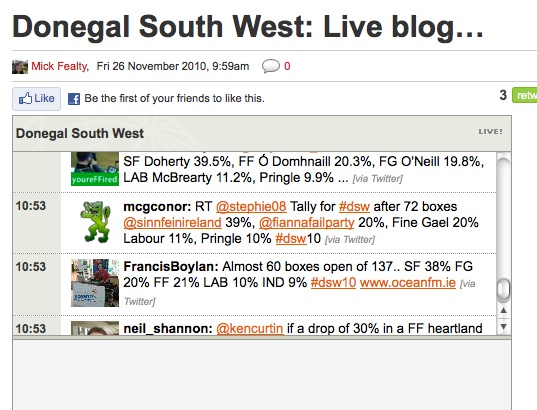

Live blogging works

Mick Fealty’s Live Blog of the count in the Donegal South West by-election is absolutely riveting.

Wanted: a new champion

In a preposterous interview on Radio 4’s Today programme, Labour’s new child prodigy, Edward Miliband, declared that he wanted to be the “champion” of the “squeezed middle”. Well then, asks my friend Andrew, “who will champion the squeezed bottom?”

Precisely. Step forward Lord Prescott.

Borderland

On a cold November day, a reminder of high Summer.

Do not try this at home

Talk about swallowing one’s pride. Or having a gut feeling about a certain track.

3,050 photographs a minute!

Just another cat picture

Larger version here.

Is the Euro doomed?

So the Irish government has published its €15 billion ‘austerity programme’ — 10 billion in public spending cuts and 5 billion in extra taxes. Since the Irish economy is a tenth of the size of the UK’s, multiply those numbers by ten to put them into a British perspective. The standard media narrative is that the cuts are the price to be paid for being ‘rescued’ by the EU and the IMF. But you could read it another way: that Ireland is rescuing the Eurozone by stopping the bond markets going for Portugal and, after that, Spain. The strange thing is that this is, almost by definition, a doomed enterprise. There is no rational way of appeasing markets when they are in irrational moods. As Keynes observed, markets can remain irrational for longer than you can remain solvent.

The more sinister possibility, of course, is that there is a semi-rational element in the nervous instability of the bond markets. Could it be that the reason they believe the bailouts won’t work is because the currency markets have decided that there’s a sporting chance of bringing down the Euro, and that significant players have begun to bet on that, in much the same way that George Soros started betting against sterling in 1987?