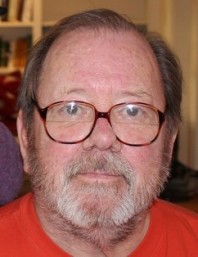

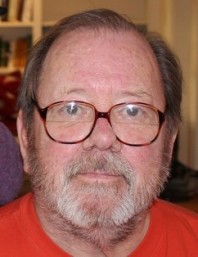

Gosh: here’s something from a vanished age. Tom West, the engineer who created Data General’s Eclipse 32-bit mini and was immortalised in Tracy Kidder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Soul of a New Machine  has died at the age of 71. He was rightly credited with saving Data General (DG) after DEC announced its VAX supermini in 1976

has died at the age of 71. He was rightly credited with saving Data General (DG) after DEC announced its VAX supermini in 1976

The Register carried a nice obit. Sample:

He was a folk singer towards the end of the 1950s and worked at the Smithsonian Observatory in Cambridge, Mass, before returning to Amherst and gaining a bachelor’s degree in Physics. He continued working at the Smithsonian, going to other observatories and ensuring that the time was precisely synchronised.

West then joined the RCA corporation and learned about computers, being largely self-taught, and then joined Data General and worked his way up the engineering ladder.

DEC shipped its VAX 32-bit supermini in 1978. This was in the era well before Intel’s X86 desktops and servers swept the board, when real computer companies designed their own processors. The 16-bit minicomputer era had boomed and DEC was the number one company. DG was the competitive number two sometimes known as ‘the bastards’ after a planned newspaper ad that never ran, and was a Fortune 500 company worth $500m. But 16-bit minis were running out of address space (memory capacity) for the apps they wanted to run.

DG launched its own 32-bit supermini project known as Fountainhead. It wasn’t ready when DEC shipped the VAX 11/780 in February 1978 and suffered from project management problems, so it is said. West, far from convinced that Fountainhead would deliver the goods, started up a secret back-room or skunkworks project called Eagle to build the Eclipse MV/8000, a 32-bit extension of the 16-bit Nova Eclipse mini. He staffed it with an esoteric mixture of people, some of them recent college graduates, and motivated them not with cash, shares or external incentives but by the sheer difficulty of what they were trying to do. It was described as pinball game management. If you got to succeed with this project or pinball game the reward was that you got to work on the next, more difficult pinball game.

DG launched its own 32-bit supermini project known as Fountainhead. It wasn’t ready when DEC shipped the VAX 11/780 in February 1978 and suffered from project management problems, so it is said. West, far from convinced that Fountainhead would deliver the goods, started up a secret back-room or skunkworks project called Eagle to build the Eclipse MV/8000, a 32-bit extension of the 16-bit Nova Eclipse mini. He staffed it with an esoteric mixture of people, some of them recent college graduates, and motivated them not with cash, shares or external incentives but by the sheer difficulty of what they were trying to do. It was described as pinball game management. If you got to succeed with this project or pinball game the reward was that you got to work on the next, more difficult pinball game.

Gordon Haff (who worked with Tom) described Kidder’s book as “perhaps the best narrative of a technology-development project ever written” and I agree with him. Its real significance, though, was that it was the first book to awaken the non-tech world to the idea that the computing business was a really vibrant, intriguing phenomenon.