Lovely spoof.

On reading (and not understanding?) Heidegger

This morning’s Observer column.

If you write about technology, then sooner or later you’re going to meet a smartarse who asks whether you’ve read Heidegger’s The Question Concerning Technology. Having encountered a number of such smartarses in recent years, I finally decided to do something about it, and obtained a copy of the English translation, published in 1977 by Harper & Row. Having done so, I settled down with a glass of sustaining liquor and embarked upon the pursuit of enlightenment.

Big mistake. “To read Heidegger,” writes his translator, William Lovitt, “is to set out on an adventure.” It is. Actually, it’s like embarking on one of those nightmares in which you’re wading through quicksand and every time you grasp a rope or a rock it comes apart in your hand. And it turns out that Heidegger’s fiendish technique is actually to lure you into said quicksand.

Rebooting the ICT curriculum

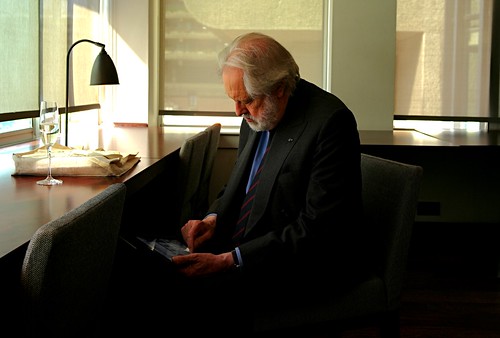

The Peer and his iPad

David (Lord) Puttnam checking email on his iPad after the Open University ceremony last Friday awarding an honorary doctorate to Cathy Casserly, the new CEO of Creative Commons.

As it happens, it was 30 years to the day since he won an Oscar for his film Chariots of Fire.

Republican philosophy: the Romney version

Lovely, succinct summary by Dave Winer:

I have a lot of money. I got it the right way. I inherited a lot of it, and then I made a lot more. Every year I make a hundred million or more. Money is a big deal for me.

And in that way I represent Republicans everywhere.

Now I know what you all want. You want my money. Hey if I were you I’d want my money too. Here’s what I have to say to that: Fuck You. I have my money and it’s mine and you can’t have it and that’s that.

In summary. 1. My money is mine. 2. Fuck you.

Those are the two basic tenets of the Republican philosophy.

That doggone geetar

Why citizens need to understand computing

Very good Guardian column by Cory Doctorow about employers snooping on employees.

Besides, there are plenty of contexts in which “company property” would not excuse this level of snooping. If you met your spouse on your lunchbreak to discuss a private medical matter in the break room or car park, you would probably expect that your employer wouldn’t use a hidden microphone to listen in on the conversation – even though you were “on company property”. Why should your employer get to snoop on your private webmail conversations with your spouse during your lunch-break?

This was what I was getting at in my essay What’s Inside the Box?: if we totalise property and elevate it above human rights, privacy and dignity, we end up in a situation where many of the devices in our lives, from the thermostats that have the power to freeze us or cook us, to the lease-purchase prostheses that let us live our lives, to the contract-subsidised mobile phones that have the power to watch our every move and record our every breath, are all designed to lock us out from controlling them – or even knowing what they’re doing.

Tree surgery

Quote of the day

“No financial man will ever understand business because financial people think a company makes money. A company makes shoes, and no financial man understands that. They think money is real. Shoes are real. Money is an end result.”

Peter Drucker

BBC Micro @30 birthday cake

Very tasty it was too.