We went for a wonderful muddy walk this morning, but eventually reached the point where we’d have needed waders to continue.

IT support is no picnic

Here’s an acronym that, I am reliably assured, is common parlance among IT Support staff:

PICNIC

It stands for “Problem in chair, not in computer”.

You have been warned.

Thanks to Andrew Ingram for enlightening me.

Norfolk in April

Yesterday on the North Norfolk coast.

Vicious Cycle

Lovely blog post by Sean French.

It seemed such a good idea at the time. We were going to visit Nicci’s parents in Worcestershire. I looked at a map and saw that we could cycle almost the whole way on the canal. We could cycle the last bit through lovely country lanes. It would take two days. I went online and booked a hotel on the banks of the canal about halfway along. It would be like those pre-First World War trips through England made by people like Edward Thomas and Hilaire Belloc.

I forgot that there were other pre-First World War trips, like those made by Captain Scott and the good ship Titanic.

But there had been a month of dought and hot sunshine, so at least the weather would be good, right?

So two days ago we set off early in the morning, joining the Regents Canal at Kings Cross. The journey out of London is strange and interesting and really, really long. It was three and a half hours before we hit real countryside. Interesting fact: from Camden Lock it’s twenty-seven miles until you reach the next lock, which means that it’s completely flat.We cycled relentlessly past familiar names: Harefield (isn’t there a heart hospital there?), Berkhamsted (where Graham Green went to the school where his father was the headmaster), Milton Keynes (in the seventies there used to be a TV commercial with the slogan: ‘Someday, all cities will be like Milton Keynes.’ I really hope not.). But it was all taking a bit too long, and then we got a puncture. And then there are towpaths and there are towpaths. Some are smooth and some are rough and some are rutted and some are like cycling through an unkempt lawn.

Darkness started to fall and you don’t want to be on a canal towpath in the middle of nowhere in pitch darkness…

You can tell he’s one half of a very successful thriller-writing duo, can’t you. I mean to say, luring the innocent reader into the horror like that.

Missing aristo in the doghouse

Breakfast 2012-04-08!

Snooping and state power

This morning’s Observer column:

The basic scenario hasn’t changed. Because of technological changes, we are told, criminals and terrorists are using internet technologies on an increasing scale. Some of these technologies (eg Skype) make it difficult for the authorities to monitor these evil communications. So we need sweeping new powers to enable the government to defend us against these baddies. These powers are as yet unspecified but will probably include “deep packet inspection” as a minimum. And, yes, these new measures will be costly and intrusive, but there will be “safeguards”.

The fierce public reaction to these proposals seems to have taken the government by surprise, which suggests ministers have been asleep at the wheel. My hunch is that the proposals were an attempt by the security services to slip one over politicians by selling them to senior officials in the Home Office, who, like their counterparts across the civil service, know sweet FA about technology and are liable to believe 10 implausible assertions before breakfast. In that sense, the Home Office has been “captured” by GCHQ and MI5 much as the health department has been captured by consultancy companies flogging ludicrous ICT projects….

Kindling

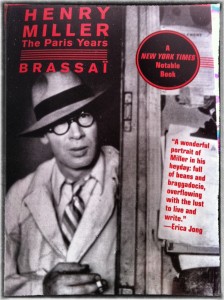

Brassai on Henry Miller

The Hungarian photographer, Brassai (whose real name was Gyula Halász), is one of my favourite artists (and a huge print of one of his most celebrated photographs — Les Escaliers de Montmartre — hangs in our dining room). But I had no idea he could write — until I stumbled on his book, Henry Miller: The Paris Years. It’s a startlingly illuminating and well-written book about a writer who was one of the photographer’s closest friends in Paris in the inter-war years, and who — until now — has always been an enigma to me.

Here’s how it opens:

“How does your memory of this compare with yours? I seem to see you standing in the Gutter at the Dome, a l’angle de la rue Delambre et Blvd Montparnasse… You had a newspaper in your hand. You told us you have begun to practice photography. It may have been the year 1931. The spot where you stood I see so vividly that I could draw a circle around it.” In a letter to me, this is how Henry Miller recalled our first meeting. “It’s strange”, he told me, “but with most people we remember neither where nor under shat circumstances we met. But I remember the first time you and I met as if it were yesterday.”

My memory doesn’t quite compare with his. My memory of the first time Henry and I met was that it took place in December 1930, shortly after he had arrived in France. My friend the painter Louis Tihanyi introduced us. Louis was sort of the Dome’s PR man — everyone recognised his olive green corduroy overcoat, worn to a shine, his wide-brimmed gray felt hat, his monocle, his fleshy lower lip. He was the spitting image of Alphonse XIII — minus the pencil mustache. Every night, table by table, Louis worked the crowded Dome terrace, which, beneath the luminous green shade of the trees on the boulevard, was always festive, as if every day were Bastille. Although deaf, and very nearly dumb as well, Louis was the best-informed man in Montparnasse. He knew not only every single one of the regulars, but the measure and worth of each newcomer.

“I want you to meet Henry Miller, an American writer,” he announced in his abrupt, guttural voice, which somehow always managed to make itself heard over the hum of conversation and the noise from the street”.

And there was Henry Miller. I will never forget the first sight of his rosy face emerging from a rumpled raincoat: the pouting, full lower lip, eyes the color of the sea. His eyes were like those of a sailor skilled at scanning the horizons through the spray. They always conveyed calmness and serenity, those eyes, and even though their expression seemed as guileless and attentive as a dog’s, they lay in ambush behind large tortoiseshell glasses…”.

I couldn’t put it down. It’s a fascinating blend of insight, affection, forgiveness and acuity. And, like Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast and Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris

, it’s beautifully evocative of an astonishing period in the life of my favourite city.

I want to be alone: Colm Toibín on solo living

From the Guardian.

On Saturday I wake at six and relishing the day ahead. I teach on Mondays and Tuesdays; I have to reread a novel for each class and take notes on it. Nothing makes me happier than the thought of this. I often lie there until the seven o’clock news comes on, grinning at the thought of the day ahead.

All day I will read and take notes. The worst-case scenario is that I might need another book, and this involves lot of decision-making and self-consultation. It might end in a five-minute walk to the university library. But normally I go nowhere except to the fridge if I am hungry to see what’s there, or to the sofa to lie down if my back is tired, or to the rocking chair if I feel a need to rock.

Normally there’s not much in the fridge. In the kitchen there is an oven I have never opened. And there are pots and pans whose purpose may be decorative for all I know. But I know where all my notebooks are. They are all over the apartment. That is the best part. I can leave them where I like and no one touches them or wants to put them away anywhere. No one sighs about books and notebooks piled up. All of the notebooks have stories half-written in them, or stray sentences in search of a home, or musings that are none of anyone’s business. If I like, I can go to one of them and add some paragraphs. I don’t have to excuse myself, explain myself, or put on a distracted writer’s look in order to get down to work. Or worry that someone has, in my absence, opened one of my notebooks and found that they don’t like the tone of what is written there.