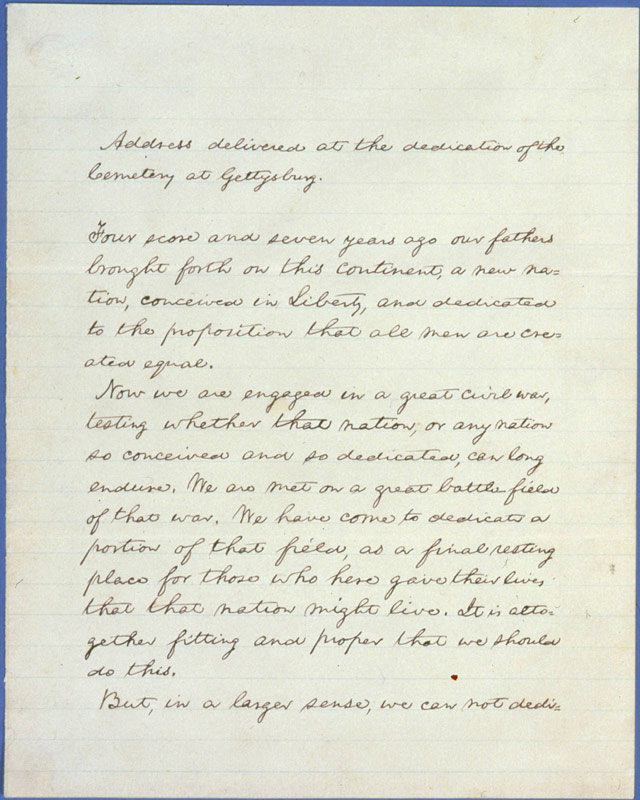

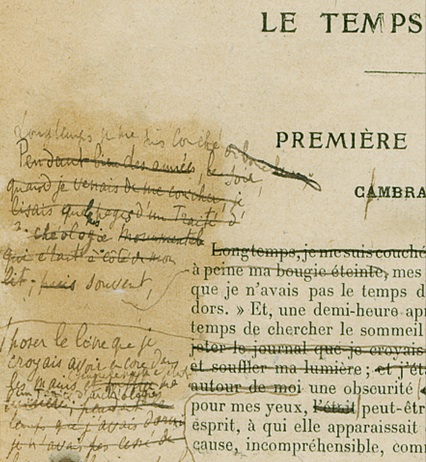

Section of a Proust page proof — from the Bibliotheque Nationale.

Today is the centenary of the publication of Du côté de chez Swann, the first volume of Marcel Proust’s sprawling masterpiece, À la recherche du temps perdu. There’s a lovely post about it by Adrian Tahourdin in the TLS Blog.

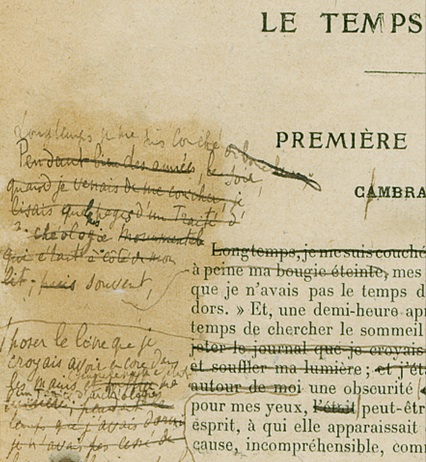

On the eve of publication Proust set out his artistic credo in Le Temps: “Je ne publie qu’un volume, Du côté de chez Swann, d’un roman qui aura pour titre général A la recherche du temps perdu. J’aurais voulu publier le tout ensemble; mais on n’édite plus d’ouvrages en plusieurs volumes. Je suis comme quelqu’un qui a une tapisserie trop grande pour les appartements actuels et qui a été obligé de la couper” (“ . . . I would have liked to have published the whole thing together, but works are no longer published several volumes at a time. I am like somebody who has a wall hanging too big for the intended rooms and who has been obliged to cut it up”). He points out that his novel “is dominated by the distinction between involuntary and voluntary memory” and goes on to stress that the “Je”, i.e. the Narrator, of the novel is not him, before concluding “The pleasure that an artist gives us, is to introduce us to another universe” – “Le plaisir que nous donne un artiste, c’est de nous faire connaître un univers de plus”. He must have known these words could be fully applied to his own forthcoming work.

The first English translation was by Scott Montcrieff, who was a journalist on the Times. One of my early mentors was a wonderful journalist, Claude Cockburn, whose first job was on the Times and who used to invite me and my girlfriend (later my wife) to his house outside Youghal in Co. Cork. In his memoirs he recalls being assigned first to the paper’s Foreign department. On entering the room, he found a long table at which sat various sub-editors poring over galley proofs and papers. At the end sat a chap who had barricaded himself behind great piles of books. “That’s Montcrieff”, explained one of the hacks. “He likes to get on with his work undisturbed”. The ‘work’, needless to say, was the translation. Those were the days.

The second English translation was by Terry (Terence) Kilmartin, who was the Literary Editor of the Observer, and the man who brought me onto the paper. But he never did any translating in the office.