I was just trying to frame this view of Anne Hathaway’s cottage from the garden when a young girl jumped up and paused to have a good look. One of those moments.

Shoring Against the Ruins

I like this passage in Colin Dickey’s review of a new critical biography of Walter Benjamin

While we tend to vacillate schizophrenically between a kind of techno-futurist cheerleading (“The future’s so bright!”) and reactionary, apocalyptic jeremiads (“The future is doomed!”), Benjamin offered another attitude towards history — one in which we walk among the ruins of an already-present catastrophe, and the highest grace is a kind of vigilant mourning. “In all mourning there is a tendency to silence, and this infinitely more than inability or reluctance to communicate,” he wrote in 1925, but if “Melancholy betrays the world for the sake of knowledge,” in its “tenacious self-absorption it embraces dead objects in its contemplation, in order to redeem them.”

The reckoning

Way back in 2008, as the full implications of the banking meltdown were beginning to become clear, I was invited to a symposium of business and economic experts convened to discuss the unfolding catastrophe. Most of them seemed pretty sanguine about the longer-term outlook: sure, there would be some pushback from the ‘austerity’ programmes that were bound to be inflicted on European societies in order to prevent the banking crisis from metamorphosing into a sovereign debt crisis; but broadly speaking it would be business as usual and things would get better in due course.

Only two people dissented from this optimistic view. One was the director of a leading business school. The other was yours truly. Why, I asked, shouldn’t the crisis eventually lead to the rise of extreme right-wing, populist political parties in the same way that the depression in Germany eventually fuelled the rise of the Nazis? The experts pooh-poohed the idea (experts are always allergic to apocalyptic talk, in my experience), so I eventually decided to shut up. After all, what do I know about economics or politics?

And now I’m sitting here in my study as the results of the European elections trickle in. UKIP heads the poll in the UK. The Far Right has made big gains in Austria (over 20% of the national vote). Ditto in Denmark (good old liberal, progressive Denmark). Ditto in Greece. Ditto in France, where even the French Prime Minister concedes that Le Pen has swept the board. And so it will go on through the night.

The BBC soothingly assures us that although the next European Parliament will be “more interesting” than its predecessors, nevertheless it there will still be a pro-European majority, so life will go on as normal.

Oh yeah?

This fractured kingdom

Walking in the grounds of Anne Hathaway’s cottage near Stratford this afternoon, we came on an extraordinary piece of sculpture, and near it this wonderful passage from Richard II.

This royal throne of kings, this sceptr’d isle

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars

This other Eden, demi-paradise

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in a silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands;

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England…

Wonder how many of the UKIP crowd know it.

Bitter XPerience

This morning’s Observer column.

It was a clear, windless night. All around was a wonderful panorama crowned by the glorious dome of St Paul’s in the distance. Then I started to look at the tall, glass-walled office blocks in my immediate vicinity. Although it was after 10pm, the lights were on in every building, enabling me to see into hundreds of offices. These offices varied in size and decor, but they all had one thing in common. Somewhere in every one of them was a desk on – or under – which stood a PC.

What then came to mind was the memory of a tousle-haired young entrepreneur named Bill Gates, who once articulated a vision of “a computer on every desk, each one running Microsoft software”. What I was looking at that December night was the realisation of that vision. Every one of the machines I could see was running Microsoft software: a software monoculture, if you like.

Microsoft’s dominance was a testimony to the power of network effects and of technological lock-in. It led to a world in which nobody ever got fired for buying Microsoft products and no software innovation gained traction unless it was designed to run under Windows.

For a time, Microsoft was the winner that took all. It would be churlish to pretend that this was all bad news, because the de facto standardisation that Microsoft brought to personal computer technology enabled the vast expansion of the PC industry and accelerated the adoption of computers in offices and homes.

But accompanying these substantial benefits there were some significant downsides…

The one-world selfie

This is amazing. And sweet. And touching. To celebrate Earth Day NASA asked people to send in pictures of where they were on that day. They received 36,000 images from over 100 countries, and assembled them into a gigantic (3.2 Gigapixel) zoomable image of the planet.

It’s the only home we’ve got. Such a pity that we’re heating it up. In the end, it will fix itself. And in the process maybe fix us too.

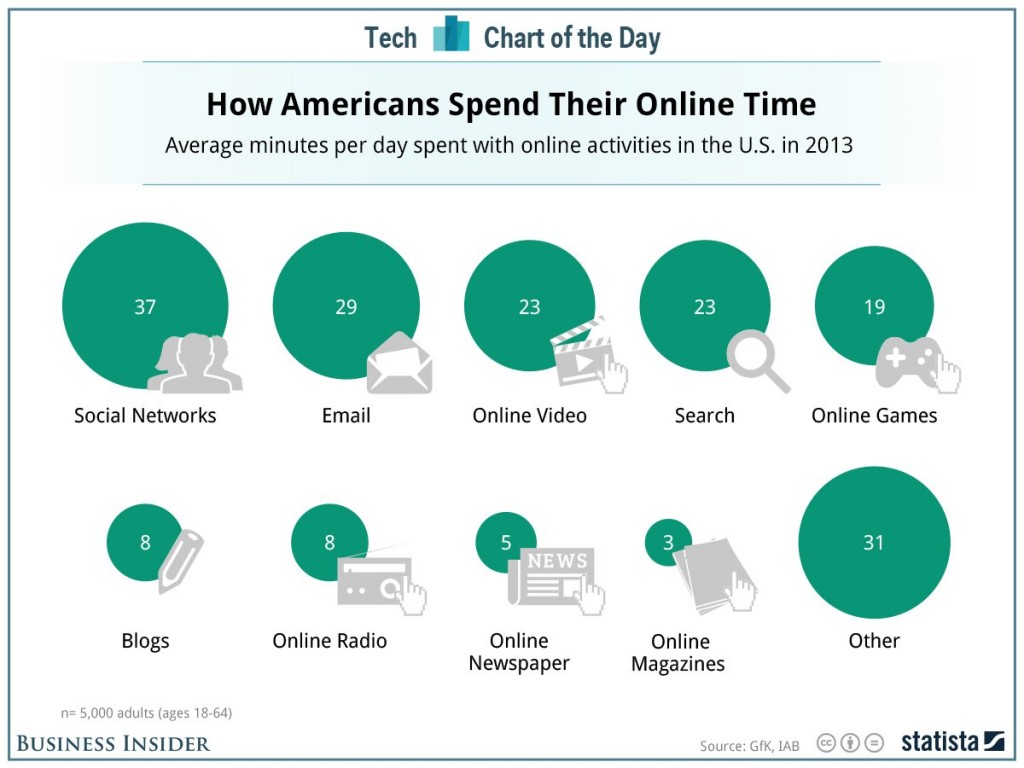

How people spend their time online

Sobering chart. Some interesting aspects: note how important email still is, despite all the talk about social networking. Note that online newspapers and magazines together only add up to the same time consumption as blogs or internet radio.

Knowingness and knowledge

“There is a difference between knowingness and knowledge, but what is it? Knowingness comes after knowledge; it is only the echo of its source, and it is proud to be the echo. One of the liberties of our connected age is that we can be almost infinitely knowing, consoling our lack of true knowledge with an easy cynicism of acquisition. It is cheaply glorious to be able to discover almost any fact about the world on the machine I am using to write this review: I experience that liberty as the reward it is, and also as a punishment; as both a gift of the digital world and a judgement on my scant acquaintance with the actual world.”

James Wood, reviewing Zia Haider Rahman’s dazzling first novel, In the Light of What We Know, in the New Yorker, May 19,2014.

Hindsight

Nice cartoon in the New Yorker. A woman is talking to a chap at a school reunion. “I liked you better as a distant memory,” she says.