Totem pole?

On a Norfolk beach.

Quote of the Day

“You feel that its words are coming of out of your body and then you dig the words into the page. It’s a physical experience.”

- The late Paul Auster on why he preferred composing in longhand.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

The Rolling Stones | Sympathy For The Devil (Live at Tokyo Dome 1990)

Well, the devil has always had the best tunes.

Long Read of the Day

The Tyranny of Content Algorithms

Nice essay by a fellow-photographer, Om Malik, on what seems to be an endemic feature of the online world.

No matter who you are, how skilled you may be, or how much knowledge you possess, excessive activity will inevitably lead to a return to the average. This phenomenon is observable every day on the Internet. Before Instagram became a competition for the lowest common denominator, there were a few photographers I followed. They consistently shared captivating images, always managing to evoke a sense of inspiration with each viewing of their work.

I wasn’t alone in this appreciation—over time, they gained more recognition and accumulated larger followings. Or perhaps it was the other way around. The ‘larger following’ meant they were able to monetize their audience. However, soon the tail was wagging the dog.

As the years passed, I noticed them sharing more frequently, yet the quality of their work declined. They gradually transitioned from being exceptional to merely average…

Perceptive piece.

The internet needs rewilding

Yesterday’s Observer column:

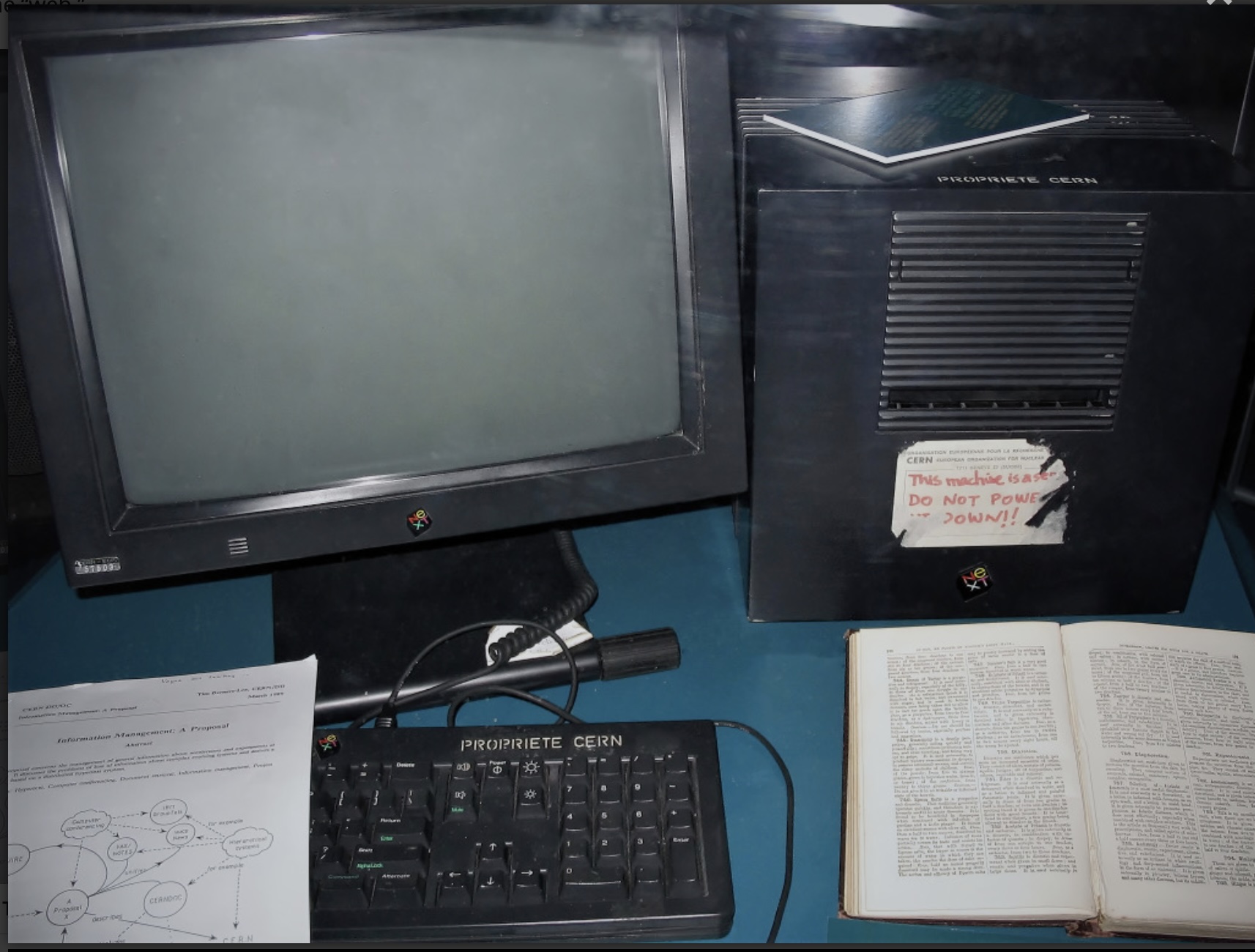

The internet was, as one scholar later described it, “an architecture for permissionless innovation” or, more prosaically, a global machine for springing surprises. The first such surprise was the web. And because it was decided the web would grow better without profit considerations, Berners-Lee released it as a platform that would also enable permissionless innovation.

However, the next generation of innovators to benefit from this freedom – Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple et al – saw no reason to extend it to anyone else. They built fabulously profitable enterprises on the platform that Berners-Lee had created. The creative commons of the internet has been gradually and inexorably enclosed, much as agricultural land was by parliamentary acts from 1600 onwards in England.

The result, as Maria Farrell and Robin Berjon put it in a striking essay in Noema magazine, is that our online spaces are no longer open ecosystems. Instead “they’re plantations; highly concentrated and controlled environments, closer kin to the industrial farms that madden the creatures trapped within”…

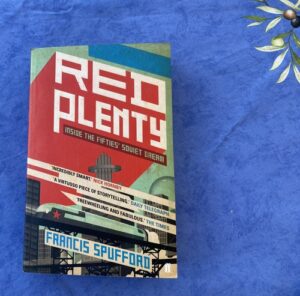

Books, etc.

This one of the most remarkable books on my shelves. Francis Spufford is a gifted polymath who can not only write great fiction (see his On Golden Hill) but also really good history of technology (see his Backroom Boys: The Secret Return of the British Boffin — published in 2003). Red Plenty, though is something else: tech history interwoven with imaginative fiction, it’s about a moment in the 1950s when some scientists and officials in the USSR thought that their country would eclipse the US with a non-capitalist model that would bring greater prosperity. (Adam Kotska’s review gives a pretty good idea of the book.)

I read it some time after it came out in 2010, but I’ve been re-reading it because in a strange way it has become salient again. As Kotska puts it,

it’s more interesting to read Red Plenty as a fairy tale about our own age, where we are stuck in an economic system that is clearly no longer delivering on its promises, but attempts to reengineer it are either squandered through half-measures or, more often, simply dismissed out of hand. People more or less live their lives in this system, as they did in the post-Stalin Soviet Union, yet with the melancholy, forcibly retired Khrushchev, we hear a rustling in the wind asking: “can it be otherwise?”

In May 2012, Henry Farrell and his fellow-bloggers on Crooked Timber organised a fascinating seminar on Spufford’s book with essays by (among others) Kim Stanley Robinson, Cozma Shalizi, George Scialabba, Antoaneta Dimitrova, Carl Caldwell, Felix Gilman and Rich Yeselson, plus responses by Francis Spufford.

Last month there was a discussion at the Santa Fe institute on the question of whether advances in computation might make possible the dream (memorably described by Spufford) that Soviet Planners had in the 1950s — of running a command economy without markets. In conjunction with the event, Henry Farrell and Francis Spufford had a fascinating conversation in the Lensic Performing Arts Center in Sante Fe. It’s an hour long, but worth eavesdropping on if you’re interested in this stuff.

My commonplace booklet

Musk loses the plot — again

One of the smartest things Tesla did at the beginning was to start building a charging infrastructure — the ‘Supercharger’ network — so that if you bought a Tesla you could charge it on the move. It was, for many of us (me included), the clinching reason for buying a Tesla rather than one of the nicer alternatives. That network was what Warren Buffett would call a ‘moat’, something that protected the company against competitors.

And now, guess what?

After firing its entire Supercharger team, Tesla has sent out an email to suppliers which shows just how chaotic the decisionmaking leading up to the firings must have been.

Earlier this week, Tesla abruptly fired its entire Supercharging team, leading to an immediate pullback in Supercharger installation plans. Now we’ve seen the email that Tesla has sent to suppliers, and it’s not pretty.

“You may be aware that there has been a recent adjustment with the Supercharger organization which is presently undergoing a sudden and thorough restructuring. If you have already received this email, please disregard it as we are attempting to connect with our suppliers and contractors. As part of this process, we are in the midst of establishing new leadership roles, prioritizing projects, and streamlining our payment procedures. Due to the transitional nature of this phase, we are asking for your patience with our response time.

I understand that this period of change may be challenging and that patience is not easy when expecting to be paid, however, I want to express my sincere appreciation for your understanding and support as we navigate through this transition. At this time, please hold on breaking ground on any newly awarded construction projects and planned pre-construction walks. If currently working on an active Supercharging construction site, please continue. Contact (email redacted) for further questions, comments, and concerns. Additionally, hold on working on any new material orders. Contact (email redacted) for further questions, comments, and concerns. If waiting on delayed payment, please contact (email redacted) for a status update. Thank you for your cooperation and patience.”

How not to run a business.

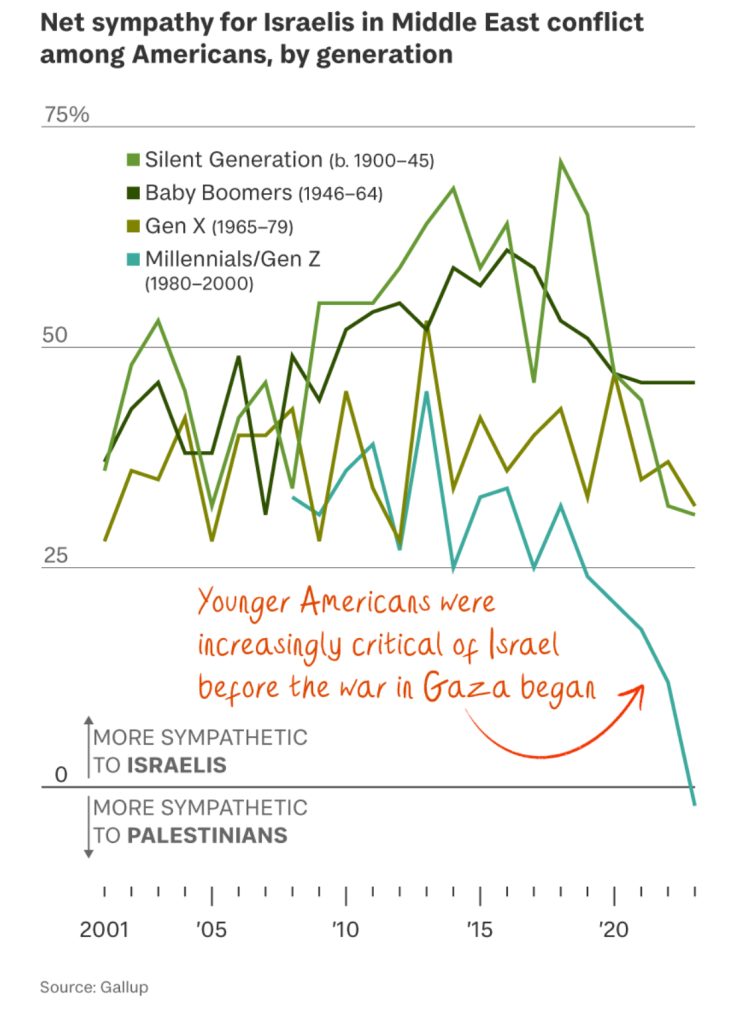

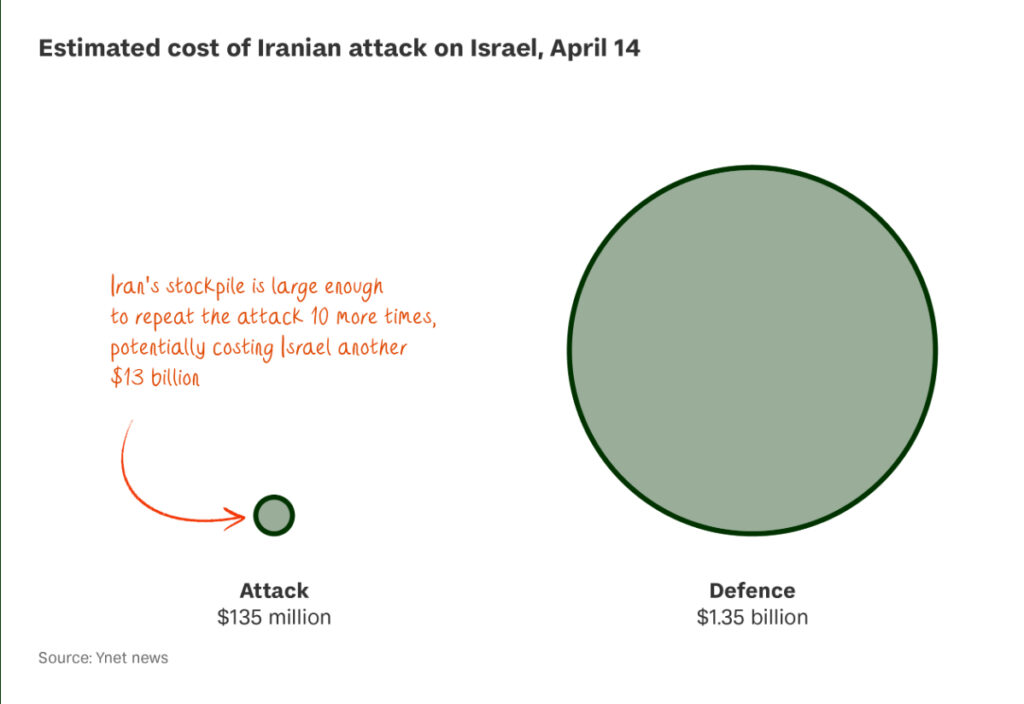

Chart of the Day

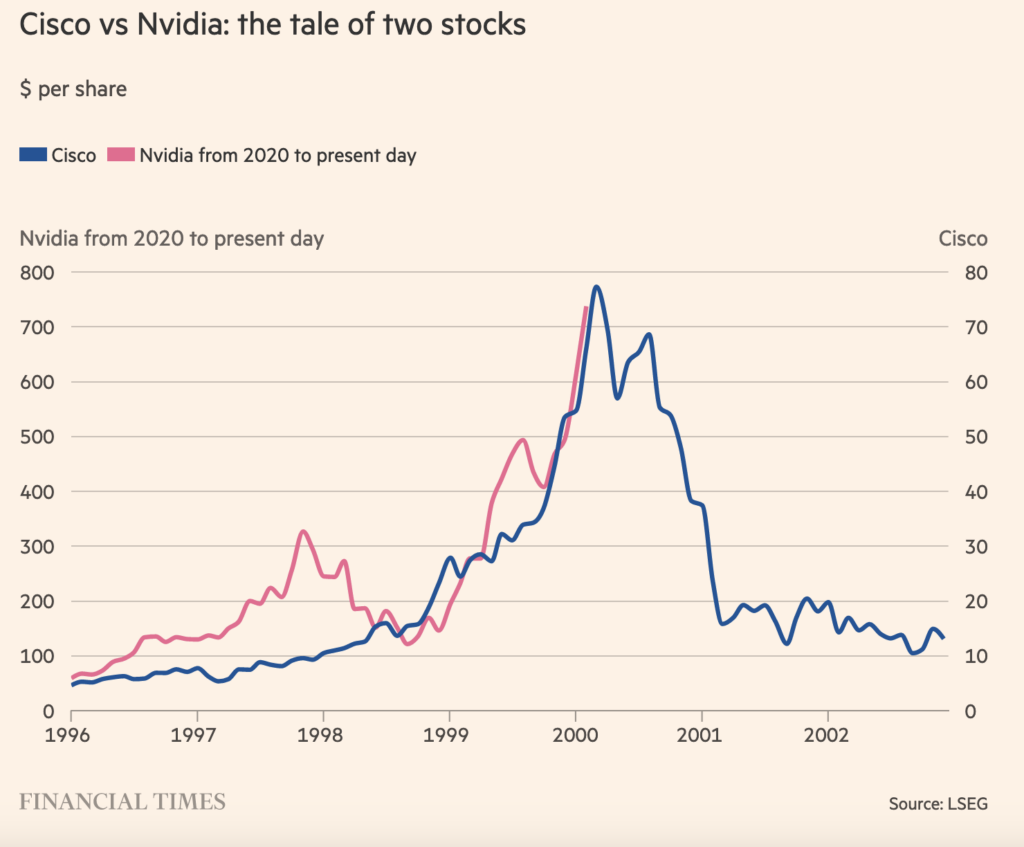

AI hype has echoes of the telecoms boom and bust

Interesting chart from the FT drawing a parallel between the first Internet boom (1995 – 2000) when Cisco routers were hot property in the same way that Nvidia GPUs are nowadays.

We’re in a bubble. Funny how nobody seems to acknowledge that.

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- Bumblebee nests are overheating to fatal levels Link

One year recently, bumble bees took over one of the nest boxes in the garden — a box that was bathed in bright sunlight for hours during the day. We were astonished to see stationary bees flapping their wings at the entrance to the box, and then twigged that they were trying to cool the nest.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!