Says it all, really.

Piping hot

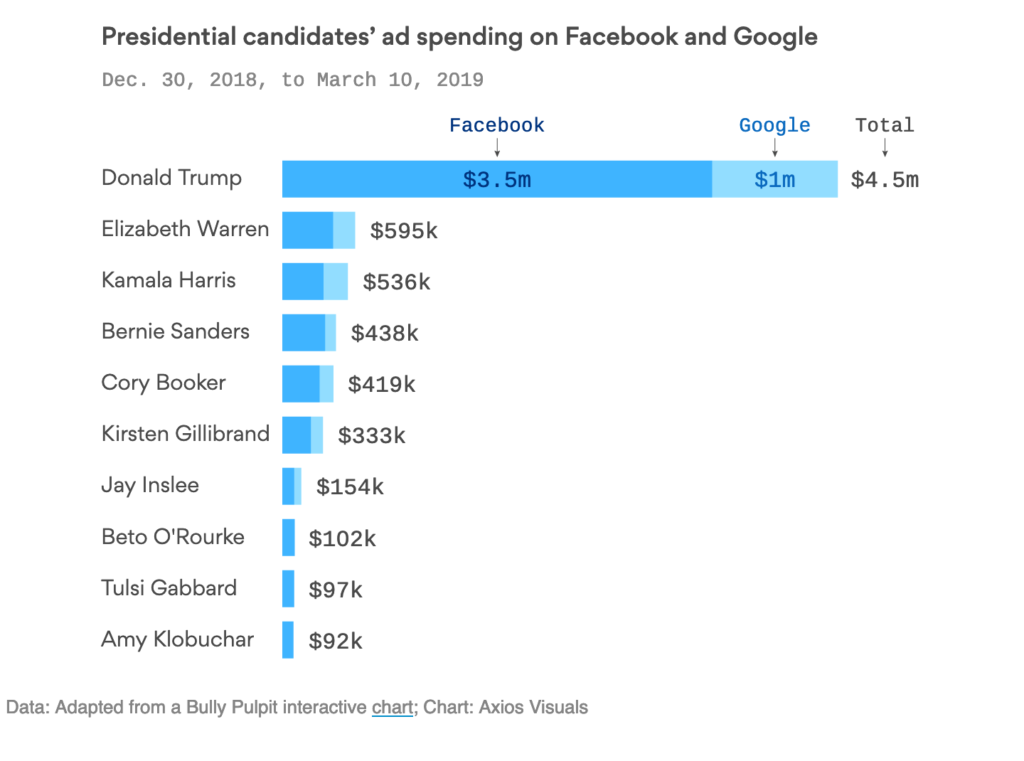

Trump 2020

Le Chat

No matter what happens now with Brexit, everybody loses

Terrific, perceptive Guardian column by Rafael Behr:

The people’s vote campaign often gets the argument about how to keep EU membership and whether to do so the wrong way round. Anyone who wants a second poll already hates Brexit. People who liked Brexit in 2016 but think it might have gone sour need something more positive to believe in than parliamentary process and referendums. The pitch has to open with the image of a happier, confident Britain, relieved of the grinding burden of endless Brexit bickering, taking its rightful seat at the top table of continental power, ready to lead. If enough people think that is the country we want to be, the case for a public vote makes itself as the way to get there.

That doesn’t mean everyone should learn the Ode to Joy and paint their face blue. It does mean that remainers must challenge the conventional wisdom that British voters are culturally immune to pro-EU arguments. There are too many MPs waiting for the architects of Brexit to soil themselves so thoroughly in absurdity and paranoia that their cause is ruined and their ideas discredited forever. But the humbling of leavers and the obstruction of their plans is not all good for remain. Not if it can be cast as the work of a conspiracy by Brussels, Whitehall and parliament.

Extension to the article 50 period is the most probable next move, which looks like a tactical gain for pro-Europeans. But engineering a situation where Britain’s EU membership survives beyond the original 29 March deadline was the easy part. The hard bit is making it look like a victory for common sense, not a defeat for national pride. Otherwise a setback for leave is no advance for remain. The crisis in British politics is severe enough that both sides can be losing at the same time.

Yep. The crisis is systemic. Even if we had a second Referendum and Remain won, the toxic divisions will continue to fester. And vice versa.

Fuchsia

Focussing on the difficulty of ‘moderating’ vile content obscures the real problem

Good OpEd piece by Charlie Warzel:

Focusing only on moderation means that Facebook, YouTube and other platforms, such as Reddit, don’t have to answer for the ways in which their platforms are meticulously engineered to encourage the creation of incendiary content, rewarding it with eyeballs, likes and, in some cases, ad dollars. Or how that reward system creates a feedback loop that slowly pushes unsuspecting users further down a rabbit hole toward extremist ideas and communities.

On Facebook or Reddit this might mean the ways in which people are encouraged to share propaganda, divisive misinformation or violent images in order to amass likes and shares. It might mean the creation of private communities in which toxic ideologies are allowed to foment, unchecked. On YouTube, the same incentives have created cottage industries of shock jocks and livestreaming communities dedicated to bigotry cloaked in amateur philosophy.

The YouTube personalities and the communities that spring up around the videos become important recruiting tools for the far-right fringes. In some cases, new features like “Super Chat,” which allows viewers to donate to YouTube personalities during livestreams, have become major fund-raising tools for the platform’s worst users — essentially acting as online telethons for white nationalists.

Quote of the Day

“If platform companies are going to provide the broadcast tools for sharing hateful ideologies, they are going to share the blame for normalizing them.”

Joan Donovan, Director of the Technology and Social Change Research Project at Harvard.

Three Farmers on their way to the future

Marvellous exegesis of one of the most memorable photographs taken by August Sander.

Are the English ready for self-government?

Lovely acerbic Irish Times column by Fintan O’Toole:

Let’s just say that if Theresa May were the head of a newly liberated African colony in the 1950s, British conservatives would have been pointing, half-ruefully, half-gleefully, in her direction and saying “See? Told you so – they just weren’t ready to rule themselves. Needed at least another generation of tutelage by the Mother Country.”

There is a surreal kind of logic to this. If, as the Brexiteers do, you imagine yourself to be an oppressed colony breaking away from the German Reich aka the European Union, perhaps you do end up with a pantomime version of the travails of newly independent colonies, including the civil wars that often follow national liberation.

What lies behind all this Brexit mania is basically English nationalism. And, as O’Toole points out,

As every former colony knows, nationalism is a great beast for carrying you to the point of independence – and then it becomes a dead horse. [George Bernard] Shaw wrote to his friend Mabel FitzGerald (mother of the future taoiseach Garret) in December 1914: “Even the subject nations like Ireland must never forget that the moment they gain home rule, the horse will drop down under them, and reveal, by a sudden and horrible decomposition, that he has been dead for years.”

Brexit is a dead horse, a form of nationalist energy that started to decompose rapidly on June 24th, 2016, as soon as it entered the field of political reality. It can’t go anywhere. It can’t carry the British state to any promised land. It can only leave it where it has arrived, in a no-man’s land between vague patriotic fantasies and irritatingly persistent facts. But equally, because of the referendum result, the British state can’t get down off the dead horse and has to keep flogging it.

I love this last image. It’s the best description of where we’re at just now.