Someone’s country seat

Actually, the result of a spot of fly-tipping.

Quote

“Reality is what I see, not what you see. “

- Anthony Burgess

Musical alternative

George Lewis | Burgundy Street Blues | with Acker Bilk & his Band (1965)

Long read of the Day

The Next Decade Could Be Even Worse

Riveting essay on the work of Peter Turchin, a quantitative historian who believes he has discovered iron laws that predict the rise and fall of societies. The key driver of this cyclical historical pattern, he believes, is a society’s “overproduction of elites”. Since you’re reading this (and I’m writing it) we’re both probably part of the problem. But it’s a great read whether or not you believe that history repeats itself.

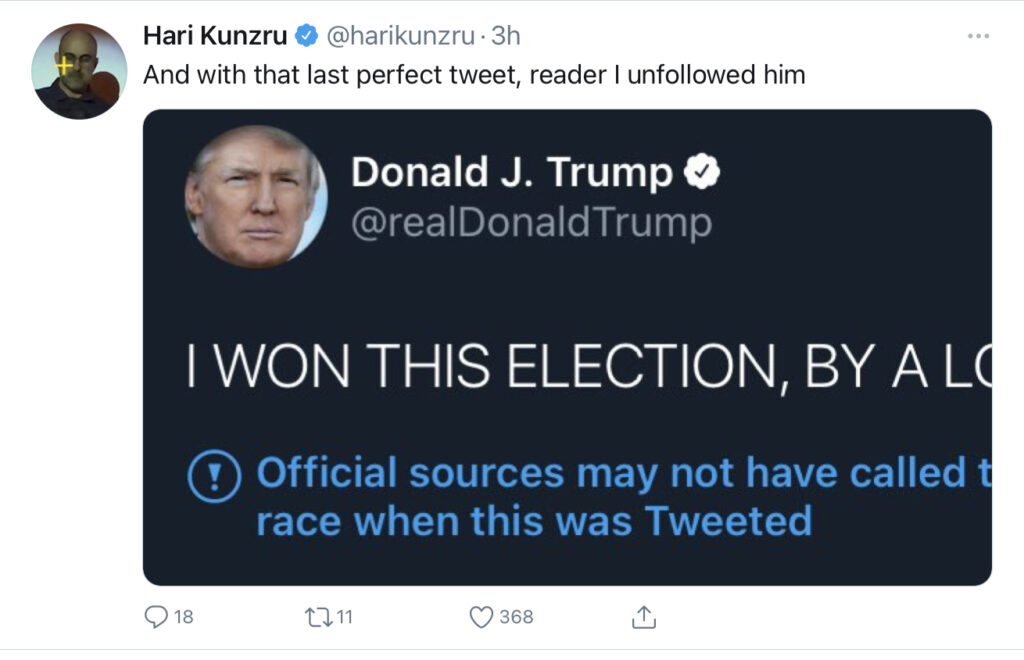

The unfollowing of Trump?

Jack Shafer on whether Trump is headed for oblivion — or not.

On the one hand…

Don’t worry about the thin squealing you hear wafting in from the White House. It’s just the sound of the last thousand cubic meters of gas escaping the rapidly deflating Trump presidency.

This doesn’t mean we’ve heard the last from Donald Trump—or that during his descent from office he’ll be incapable of causing mischief and detonating crises. But given the way the attention economy works, with each passing day he will become less and less relevant as the bilge and sewage of his “rigged” and “stolen” election protests move deeper and deeper inside the A section of the newspaper and our focus toggles instead to the Biden presidency, Covid-19 fallout, the economy, foreign entanglements, natural catastrophes and the endless surprises the future brings. Trump’s slide from the political A list to the B list and maybe even the C list will be secured on Jan. 20, when Joe Biden takes the oath, so if you plan on missing him once he’s gone, prepare yourself for his vanishing act now.

On the other hand…

Trump has always disrupted the natural laws of news, so his ex-presidency should be allowed a few exemptions. For one thing, Trump, unlike term-limited presidents or other incumbents who’ve lost, has already signaled an ongoing involvement in politics and perhaps another run in 2024. Many of his 73 million voters will still heed his messages, donate to his permanent campaign, tune in when he phones Fox & Friends, cloister in airplane hangars for his rallies, and watch him on his new TV channel if he nabs one. He is, after all, the man who enjoyed campaigning for president more than actually being president.

On balance, Shafer seems unusually (for him) optimistic:

There is no criticism like the criticism of straightforward indifference,” Alexander Cockburn wrote in 1986. As the ritual of inauguration gathers speed, as every third word on cable news and the front pages is about Biden and Kamala Harris, as the imperial powers of the presidency change hands, and as Trump slinks off to his exile in Mar-a-Lago, Trump will feel something close to straightforward indifference as the nation finally unfollows him.

The Obama interview

In The Atlantic.

Which brought him to his main point: “America as an experiment is genuinely important to the world not because of the accidents of history that made us the most powerful nation on Earth, but because America is the first real experiment in building a large, multiethnic, multicultural democracy. And we don’t know yet if that can hold. There haven’t been enough of them around for long enough to say for certain that it’s going to work,” he said.

The threats to American democracy—and to the broader cause of freedom—are many, he said. He was withering on the subject of Donald Trump, but acknowledged that Trump himself is not the root of the issue. “I’m not surprised that somebody like Trump could get traction in our political life,” he said. “He’s a symptom as much as an accelerant. But if we were going to have a right-wing populist in this country, I would have expected somebody a little more appealing.”

Trump, Obama noted, is not exactly an exemplar of traditional American manhood. “I think about the classic male hero in American culture when you and I were growing up: the John Waynes, the Gary Coopers, the Jimmy Stewarts, the Clint Eastwoods, for that matter. There was a code … the code of masculinity that I grew up with that harkens back to the ’30s and ’40s and before that. There’s a notion that a man is true to his word, that he takes responsibility, that he doesn’t complain, that he isn’t a bully—in fact he defends the vulnerable against bullies. And so even if you are someone who is annoyed by wokeness and political correctness and wants men to be men again and is tired about everyone complaining about the patriarchy, I thought that the model wouldn’t be Richie Rich—the complaining, lying, doesn’t-take-responsibility-for-anything type of figure.”

He sees the origin of the populist wave in the choice of Sarah Palin as John McCain’s running-mate. The wave was abetted by Fox News and other right-wing media outlets, he said, and encouraged to spread by social-media companies uninterested in exploring their impact on democracy.

“I don’t hold the tech companies entirely responsible because this predates social media. It was already there. But social media has turbocharged it. I know most of these folks. I’ve talked to them about it. The degree to which these companies are insisting that they are more like a phone company than they are like The Atlantic, I do not think is tenable. They are making editorial choices, whether they’ve buried them in algorithms or not. The First Amendment doesn’t require private companies to provide a platform for any view that is out there.”

“If we do not have the capacity to distinguish what’s true from what’s false, then by definition the marketplace of ideas doesn’t work. And by definition our democracy doesn’t work. We are entering into an epistemological crisis.”

Interesting throughout. Reminds one of what a serious politician is like.

Other, hopefully interesting, links

- Lego creates largest set ever: Rome’s Colosseum with 9,036 pieces. Link.

- Jeremy Mayer’s astonishing sculptures. The write stuff: made from old typewriters. Thanks to Cory for the Link.

- In Which a Cat Narrates Feline History in the Age of European Conquest. Well, the Ancient Egyptians worshipped them as gods. Link

- The Donald J. Trump Presidential Library. Wonderfully clever spoof. Link. Many thanks to James Miller, Whom God Preserve, for the link.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!