Make the Earth move…

… But on no account push.

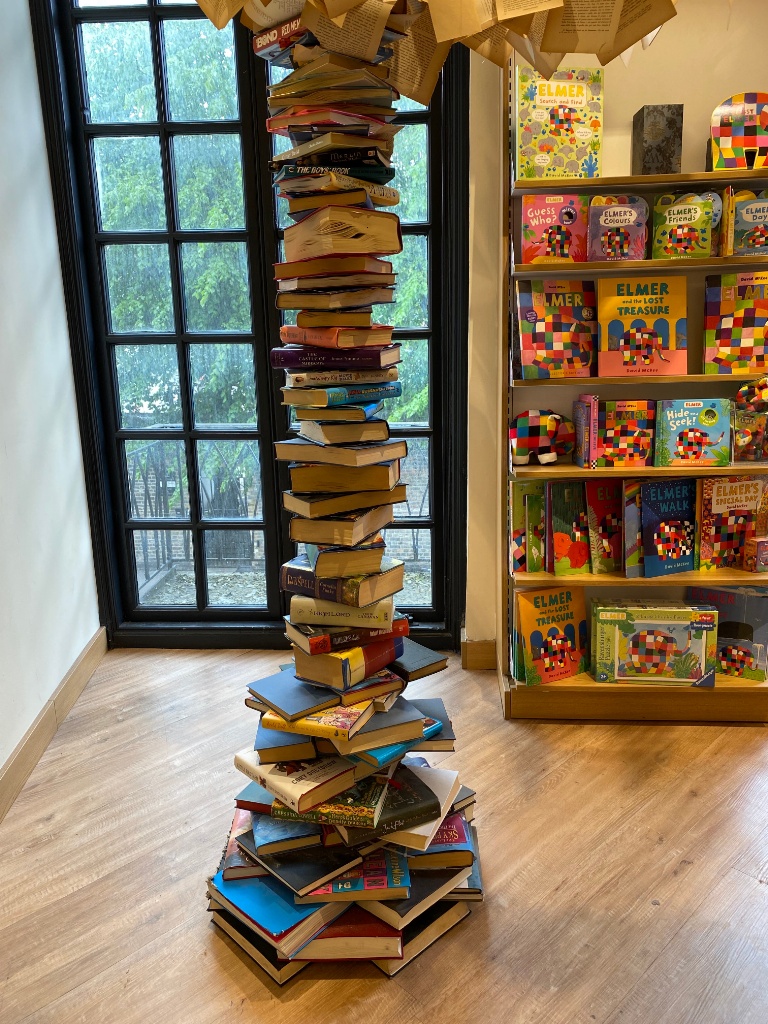

Seen on a journey the other day.

Quote of the Day

”Now there sits a man with an open mind. You can feel the draft from here.”

- Groucho Marx on Chico

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Handel | Suite No. 5 | Sviatoslav Richter

Long Read of the Day Monopolists are winning the repair wars

Marvellous long blog post by Cory Doctorow on the way an increasing percentage of vital machinery is being controlled by monopolistic manufacturers. This is not just about Apple trying to make sure that nobody except Apple repairs your iPhone. Ditto medical equipment. Ditto modern tractors. And so on. It explains why the ‘right to repair’ is an important issue, and why the power of corporate lobbying to prevent it is so damaging and environmentally disastrous.

Uber finally recognises a trade union — the GMB

Well, well. This from the Guardian:

Uber is to recognise the GMB trade union in the UK for its private hire drivers, marking the first deal between a union and a gig economy ride-hailing service.

Under the recognition deal, the GMB will have access to drivers’ meeting hubs to help and support them. It will also be able to represent drivers if they lose access to the Uber app, and it will meet quarterly with management to discuss driver issues and concerns.

Drivers will not become members automatically but will be able to sign up to take part in collective bargaining.

Uber has signed the deal two months after agreeing to guarantee its 70,000 UK drivers a minimum hourly wage, holiday pay and pensions in March after a landmark supreme court ruling.

But (there’s always a but)…

The union recognition agreement, like the pay deal, does not apply to delivery riders for the Uber Eats food service, which works with about 30,000 couriers.

Still, as the Chinese say, the longest journey begins with a single step.

Who knows, maybe one day I might use Uber?

Britain’s electric car charging network gets a boost

Today’s Guardian reports that:

Britain’s energy regulator has approved a £300m investment spree to help triple the number of ultra-rapid electric car charge points across the country, as part of efforts to accelerate the UK’s shift to clean energy.

Ofgem has given the green light for energy network companies to invest in more than 200 low-carbon projects across the country over the next two years, including the installation of 1,800 new ultra-rapid car charge points for motorway service stations and a further 1,750 charge points in towns and cities.

The regulator hopes the extra investment to make car charging points more convenient will help to address motorist “range anxiety”, which is frequently mentioned as a key reason why drivers are wary about choosing an electric vehicle over a fossil fuel model.

The UK plans to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030 and phase out hybrid vehicles from 2035 as part of its plan to reduce road transport emissions. However, only 11% of new car registrations last year were for ultra-low emission cars.

This is interesting because I suspect there’s a race on between EV adoption and the rate at which the charging infrastructure expands.

Other, hopefully interesting, links

- Sites of the graves of famous economists Of arcane interest, I grant you, but I was intrigued to find that Keynes’s ashes were not — as his will stipulated — deposited in the crypt of his College (King’s, Cambridge) but scattered on the Downs at Tilton, his country estate. Link

- The Dubrovnik Interviews: Marc Andreessen – Interviewed by a Retard. You thought Elon Musk was nuts? Well, try Marc Andreessen — as portrayed in this interview by Niccolo Soldo doing a fair impression of Hunter S Thompson on speed. Link

- Stairway to Heaven as you’ve never heard it sung before Link

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!