Dreaming…

… of making a sale perhaps? Seen in a Provencal market.

Quote of the Day

”New money shouts. Old money whispers.”

- Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Mick Flannery | Boston

Long Read of the Day

Big Serious Books Can Really Be Your Intellectual Friends

A lovely essay by Brad DeLong that he had dug out of his archives in which he muses about the importance of books he has read in the past.

Here’s how it opens:

There are urgent, human voices behind the books on your shelf. Let Niccolò Machiavelli remind you: the best intellectual company is always within arm’s reach. Don’t ask “what if your library could talk back?” Recognize that it can and does, if you have the right kind of mind to engage in deep, close, active reading. Shift from thinking of yourself as engaged in an academic ratrace. Instead take the black squiggles on the page that is the information code, and from them spin-up a SubTuring instantiation of the mind of the author of the book, and run it on your wetware. And argue with it.

Thus books transform from dry texts into lively interlocutors—and being able to see that shift might just save your sanity. Treat your books as people, not objects.

Then step into the ancient courts of ancient thinkers, and find yourself among true friends.

And afterwards, you feel like Dante claimed he had felt:

I saw the Master of the Men who Know,

seated in philosophic family….

There all look up to him, all do him honor:

there I beheld both Socrates and Plato,

closest to him, in front of all the rest;

Democritus, who ascribes the world to chance,

Diogenes, Empedocles, and Zeno,

and Thales, Anaxagoras, Heraclitus;

I saw the good collector of medicinals,

I mean Dioscorides; and I saw Orpheus,

and Tully, Linus, moral Seneca;

and Euclid the geometer, and Ptolemy,

Hippocrates and Galen, Avicenna,

Averroés, of the great Commentary.

I cannot here describe them all in full;

my ample theme impels me onward so:

what’s told is often less than the event…

Musk and co should ask AI what defines intelligence. They may learn something

Sunday’s Observer column:

In 1999, two psychologists, David Dunning and Justin Kruger, came up with an interesting discovery that is now known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. It refers to a cognitive bias where individuals with low ability in a specific area overestimate their skills and knowledge. This occurs because they lack the self-awareness to accurately assess their own competence compared with others. The US president is a textbook example, but so too are many inhabitants of Silicon Valley, especially the more evangelical boosters of AI such as Elon Musk and OpenAI’s Sam Altman.

Both luminaries, for example, are on record as predicting that AGI (artificial general intelligence) may arrive as soon as next year. But when you ask what they mean by that, we find the Dunning-Kruger effect kicking in. For Altman, AGI means “a highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work”. For Musk, AGI is “smarter than the smartest human”, which boils down to a straightforward intelligence comparison: if an AI system can outperform the most capable humans, it qualifies as AGI.

These are undoubtedly smart cookies. They know how to build machines that work and corporations that one day may make money. But their conceptions of intelligence are laughably reductive, and revealing, too: they’re only interested in economic or performance metrics. It suggests that everything they know about general intelligence (the kind that humans have from birth) could be summarised in 95-point Helvetica Bold on the back of a postage stamp…

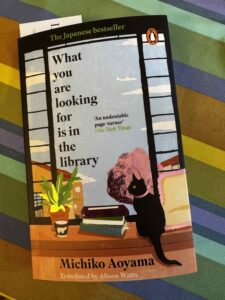

So many books, so little time

If you love libraries then you might enjoy this little Japanese novel which I came across in a French bookstore. It’s about a disparate group of individuals who are, in one way or another, drifting, and who visit a particular library in search of answers to questions that bother them. In a way it’s an endearing tribute to the transformative power of libraries. And to this blogger, whose life was transformed in the 1950s by a Carnegie library in a small Irish town, it resonates.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!