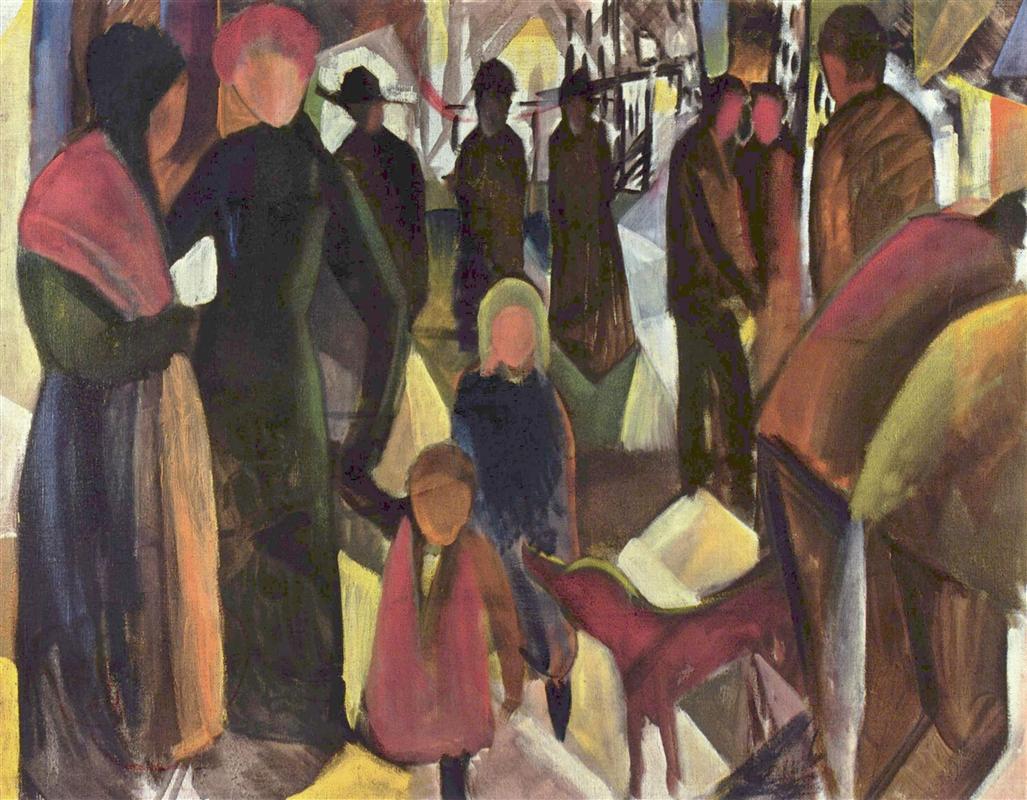

Peace on Earth (well, in a small corner of it anyway)

What did this scene remind me of? See today’s Musical Alternative for the answer.

Quote of the Day

”Politics is not the art of the possible. It consists in choosing between the disastrous and the unpalatable.”

- John Kenneth Galbraith

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

J. S. Bach | Cantata Nº 208, ‘Sheep May Safely Graze’, BWV 208

Long Read of the Day

The Strange Rebirth Of Imperial Russia

Unmissable essay by Andrew Sullivan on what most of us have missed about the newly visible monster of post-Communist Russia. “It would be hard to conjure up a period of post-modern bewilderment more vividly than Russia in the post-Soviet 1990s”, he writes.

A vast empire collapsed overnight; an entire totalitarian system, long since discredited but still acting as some kind of social glue and cultural meaning, unraveled in chaos and confusion.

Take away a totalitarian ideology in an instant, and a huge vacuum of meaning will open up, to be filled by something else. We once understood this. When Nazi Germany collapsed in total military defeat, the West immediately arrived to reconstruct the society from the bottom up. We de-Nazified West Germany; we created a new constitution; we invested massively with the Marshall Plan, doing more for our previous foe than we did for a devastated ally like Britain. We filled the gap. Ditto post-1945 Japan.

But we left post-1991 Russia flailing, offering it shock therapy for freer markets, insisting that a democratic nation-state could be built — tada! — on the ruins of the Evil Empire. We expected it to be reconstructed even as many of its Soviet functionaries remained in place, and without the searing experience of consciousness-changing national defeat. What followed in Russia was a grasping for coherence, in the midst of national humiliation. It was more like Germany after 1918 than 1945. It is no surprise that this was a near-perfect moment for reactionism to stake its claim.

It’s a really interesting piece which illuminates something I’ve wondered about from the beginning, which is that Putin isn’t trying to reclaim the territory lost by the USSR in 1989-91, but to redraw the boundaries of Russia to those that obtained when the Tsar ruled!

If the war ends in manifest Russian failure, Sullivan says, then “Putin is surely finished”. But if it becomes a long-drawn-out grinding mess, then he might survive and emerge stronger. Russia, after all, has in the past been good at winning wars of attrition — ask Napoleon’s or Hitler’s ghosts.

Putin had a 21st-century digital battle plan, so why is he fighting like it’s 1939?

Yesterday’s Observer column:

One thing at least we know about Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine: it isn’t going according to plan. Ah, yes, you reply, but which plan? Was it plan A, which simply said that you assemble enough conscripts and heavy artillery, roll into Ukraine, shell a few apartment blocks, amble across to Kyiv and have a victory parade? What we call the George W Bush model (except that he had his Iraq victory parade on the flight deck of an American aircraft carrier).

If this was plan A, then we know what plan B is. It’s to do to Ukraine what was done to the statelet of Chechnya in 1999, namely bomb it to rubble regardless of civilian casualties. Apart from its intrinsic inhumanity, trying to implement this plan in Ukraine faces some practical difficulties: Ukraine is vast whereas Chechnya is small, and Ukraine has a serious army, a feisty capability for resistance and a plentiful supply of serious weaponry from its friends in the west. So if Putin wants a primer before embarking on the next stage of his imperial adventure, he should perhaps download Charlie Wilson’s War, an instructive film about what happened to the USSR in Afghanistan all those years ago.

For those who follow these things professionally, the biggest puzzle is why Putin embarked on a campaign that looks like the second world war in Technicolor, when his military actually had an ultra-sophisticated plan for warfare in a digital age. It’s called the Gerasimov doctrine and it was the creation in 2013 of Valery Gerasimov, a smart lad who is chief of the general staff and first deputy defence minister of the Russian Federation…

Why have Ukraine’s ‘clay pigeons’ been so successful against Russian targets?

As Putin tries to pretend that the Russian swerve back to Donbas was what he always intended, one of the intriguing aspects of the war so far has been the effectiveness of humdrum aerial warfare — in the shape of the relatively low-tech Turkish Bayraktar drones against the invaders’ supposedly invincible armoured columns. This piece entertainingly explores that mystery.

Before the war began, military experts predicted that Russian forces would have little trouble dealing with Ukraine’s complement of as many as 20 Turkish drones. With a price tag in the single-digit millions, the Bayraktars are far cheaper than drones like the U.S. Reaper but also much slower and smaller, with a wingspan of 39 feet.

As so often has been the case in this war, however, the experts misjudged the competence of the Russian military.

“It’s quite startling to see all these videos of Bayraktars apparently knocking out Russian surface-to-air missile batteries, which are exactly the kind of system that’s equipped to shoot them down,” said David Hambling, a London-based drone expert.

That is confounding, Hambling said, because the drones should be easy for the Russians to blow out of the sky — or disable with electronic jamming.

“It is literally a World War I aircraft, in terms of performance,” he said. “It’s got a 110-horsepower engine. It is not stealthy. It is not supersonic. It’s a clay pigeon — a real easy target.”

Eh? A million dollars each is ‘cheap’? Explains why arms manufacture is such a profitable racket.

Why does Tucker Carlson sound like a Berkeley leftist?

Antonio García Martínez on how the war in Ukraine has exposed an ideological vacuum at the heart of American right. Unlike many of the commentary at, he actually went to see for himself.

I spent last week reporting from Poland and Ukraine myself. It was more than a bit eye-opening: The refugee crisis on the border is enormous, Europeans have mobilized tremendously to handle it, and Ukraine itself is on a total war footing where all thought and action go toward victory over the Russian invaders.

On the way back, I was standing in line along with Ukrainian refugees to re-enter the EU zone at a desolate rural crossing point. After all the hours it took to get through, there was a collective euphoria (much stronger among the refugees surely than me) upon entering the European Union and NATO. The line between the worlds of war and destruction and desperation and that of order and safety and prosperity was very stark indeed.

Those who rail constantly against the global liberal order should step outside it every now and then. They might appreciate it more. After all, there’s no law of the physical universe that we must always live in democracies with rule of law. That’s the historical exception not the rule.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!