Parallel reflections

On a country walk late yesterday afternoon we came on a pair of cygnets dabbling in a small lake. After a while, one of them began to swim away. As I watched him move into open water, I suddenly noticed the silhouette of the submerged curved branch in the background and took several shots trying to catch what Henri Cartier-Bresson famously called ‘the decisive moment’ — and then got this.

In a way, dear old HCB has a lot to answer for. Millions of photographers are forever looking for a way of capturing one of those moments. And mostly not finding them — so when it happens it’s worth celebrating.

Quote of the Day

A poem for Boris

I could not dig:

I dared not rob:

Therefore I lied to please the mob.

Now all my lies are proved untrue

And I must face the men I slew.

What tale shall serve me here among

Mine angry and defrauded young?

- ‘A Dead Statesman’, Rudyard Kipling (from ‘Epitaphs of the War 1914-18’). Chosen by Alan Bennett in his 2021 Diary in the London Review of Books.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Gustav Holst | In the bleak midwinter

Link

My favourite Christmas carol.

Long Read of the Day

This Scientist Created a Rapid Test Just Weeks Into the Pandemic. Here’s Why You Still Can’t Get It.

Yesterday I went to three pharmacies to try and get some more of the lateral-flow Covid test kits that the UK government says are an essential tool for families and workers trying to be careful about catching or passing on Covid over Christmas. None of the pharmacies had any supplies. They’d run out after the (predictable) surge in demand after the government had started recommending them in the run-up to the festive season.

This dearth will probably be rectified soon. It’s a reminder of why this Christmas feels so different from 2020. Then, we didn’t have any vaccines. And we didn’t have many DIY test kits either.

One reason why this terrific ProPublica story by Lydia DePillis is so interesting is that it reveals that the US could have had something like a lateral-flow test at the very beginning of the pandemic. Way back in early 2020, a Harvard-trained scientist named Irene Bosch developed a quick, inexpensive COVID-19 test. She already had a factory set up to manufacture it for $10 a shot. On March 21, 2020 — when the U.S. had recorded only a few hundred COVID-19 deaths — she submitted her test for emergency authorisation, a process that the Food and Drug Administration uses to expedite tests and treatments. But the go-ahead never came.

How did this happen? Well, as you might expect, it’s a long story. And it’s worth a read.

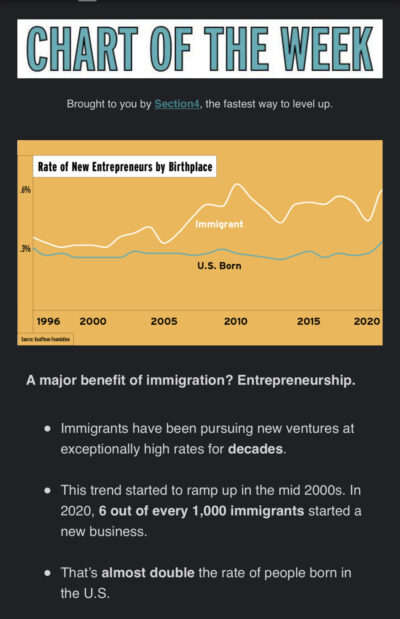

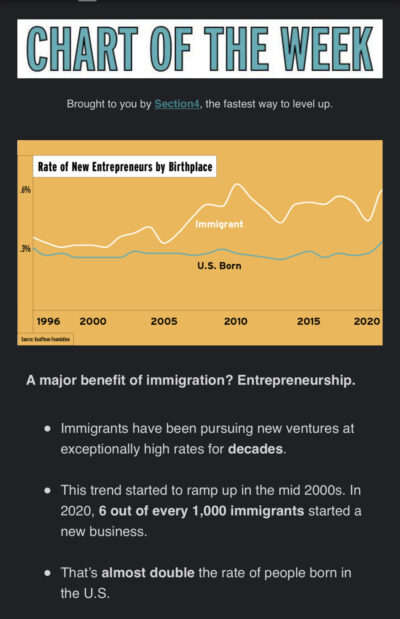

Chart of the Day

Why immigrants are important

One reason is that more of them start businesses than citizens of their host nations. These are the figures for the US. Wonder what they’re like for, say, the UK.

Stuart Russell’s Reith Lectures: ‘Living with Artificial Intelligence’

They’re terrific. And available on the BBC Sounds app and via the website. And if you’re too busy to listen, why not download the transcripts — also from the website?

Remembering Christopher Hitchens

Hitchens died ten years ago this month and there have been a number of nice essays by writers and journalists who knew and admired him. This one by Graydon Carter, who was Editor of Vanity Fair from 1992 to 2017, is the latest to come my way, and it’s lovely:

If you ever had the good fortune to spend time with Christopher, as I did over long lunches and even longer dinners, you would have been an audience to one of the more spectacular minds in recent history. There was nothing Christopher hadn’t read and couldn’t recall from memory. Late into the night and well into his cups, he could recite Gussie Fink-Nottle’s prize-giving speech at Market Snodsbury Grammar School—and precisely the way P. G. Wodehouse wrote it. Like all sane people, he considered Wodehouse the greatest practitioner of the English language.

I was often annoyed by Hitchens, but generally mesmerised by his prose, and so as a way of personally marking his passing I started to read my way through the archive of things he wrote for the London Review of Books. It’s an eye-opener.

A good test of a writer is when he or she tackles something that you think you know about and wind up seeing it in a completely different light when you’ve finished the piece. A instructive example in this context is his review of Michael Ignatieff’s biography of Isaiah Berlin, which I thought was terrific because it helped me finally to understand why so many people whom I took seriously seemed to be in awe of Berlin. But Hitchens saw through him, and yet wasn’t vindictive.

The anecdotal is inescapable here, and I see no reason to be deprived of my portion. I first met Berlin in 1967, around the time of his Bundy/Alsop pact, when I was a fairly tremulous secretary of the Oxford University Labour Club. He’d agreed to talk on Marx, and to be given dinner at the Union beforehand, and he was the very picture of patient, non-condescending charm. Uncomplainingly eating the terrible food we offered him, he awarded imaginary Marx marks to the old Russophobe, making the assumption that he would have been a PPE student. (‘A beta-alpha for economics – no, I rather think a beta – but an alpha, definitely an alpha for politics.’) He gave his personal reasons for opposing Marxism (‘I saw the revolution in St Petersburg, and it quite cured me for life. Cured me for life’) and I remember thinking that I’d never before met anyone who had a real-time memory of 1917. Ignatieff slightly harshly says that Berlin was ‘no wit, and no epigrams have attached themselves to his name’, but when he said, ‘Kerensky, yes, Kerensky – I think we have to say one of the great wets of history,’ our laughter was unforced. The subsequent talk to the club was a bit medium-pace and up-and-down the wicket, because you can only really maintain that Marx was a determinist or inevitabilist if you do a lot of eliding between sufficient and necessary conditions. But I was thrilled to think that he’d made himself vulnerable to such unlicked cubs. A term or two later, at a cocktail party given by my tutor, he remembered our dinner, remembered my name without making a patronising show of it, and stayed to tell a good story about Christopher Hill and John Sparrow, and of how he’d been the unwitting agent of a quarrel between them, while ignoring an ambitious and possessive American professor who kept yelling ‘Eye-zay-ah! Eye-zay-ah!’ from across the room. (‘Yes,’ he murmured at the conclusion of the story. ‘After that I’m afraid Christopher rather gave me up. Gave me up for the Party.’)

Many years later, reviewing Personal Impressions for the New Statesman, I mentioned the old story of Berlin acting as an academic gatekeeper, and barring the appointment of Isaac Deutscher to a chair at Sussex University. This denial had the sad effect of forcing Deutscher – who had once given Berlin a highly scornful review in the Observer – to churn out Kremlinology for a living: as a result of which he never finished his triad or troika of Stalin, Trotsky and Lenin biographies. In the next post came a letter from Berlin, stating with some anguish that while he didn’t much approve of Deutscher, his opinion had not been the deciding one. I telephoned Tamara Deutscher and others, asking if they had definite proof that Berlin had administered the bare bodkin, and was told, well, no, not definite proof. So I published a retraction. Then came a postcard from Berlin, thanking me handsomely, saying that the allegation had always worried and upset him, and asking if he wasn’t correct in thinking that he had once succeeded more in attracting me to Marxism than in repelling me from it. I was – I admit it – impressed. And now I read, in Ignatieff’s book, that it was an annihilatingly hostile letter from Berlin to the Vice-Chancellor of Sussex University which ‘put paid to Deutscher’s chances’. The fox is crafty, we know, and the hedgehog is a spiky customer, and Ignatieff proposes that the foxy Berlin always harboured the wish to metamorphose into a hedgehog. All I know is that I was once told – even assured of – one small thing.

Carter’s tribute is gracious and affectionate, without being smarmy. This is how it finishes:

Christopher was also a spirited defender of free speech, whether it came out of the mouths of monsters or political idiots on the right or the left. His across-the-board defense often made people uncomfortable back in the day. I’m not sure he’d survive the current cancel-culture mobs—let alone the op-ed page of The New York Times. That very fearlessness would be his undoing if he were on the speaking-circuit prowl today.

One thing I do believe: The Christopher Hitchens I knew and adored wouldn’t be like the majority of us, huddling in our trembling silence, terrified of saying what we really think, and shaking our heads in the belief that the world has gone mad and the other side is the one destroying America. Christopher would be out there on the front lines. I just wish I knew which front lines he’d be on.

My commonplace booklet

Ten Things to Say Instead of “No Thanks, I Don’t Drink”

Useful advice for the office party season from Lindsey Adams.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!