Art paying homage to Technology

Steve Russell’s Zoom-gallery portrait

My friend and former colleague, Joe Smith, who is now Director of the Royal Geographical Society, sent me a link to this innovative way of using an ancient medium to pay homage to a modern one. It’s a Zoom meeting portrait of nine people who, Joe says, have helped keep the RGS show on the road during COVID. “In an institution that has quite a few moustachio’d 19th-century bloke portraits on the walls”, he writes, “this is a refreshing expression of who we are today”. It’s also one answer to the question of how a venerable institution can hold a memory of COVID, and show gratitude to the people who ‘got us through’.

Quote of the Day

”His pictures seem to resemble, not pictures, but a sample book of patterns of linoleum.”

- Cyril Asquith on Paul Klee

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Franz Schubert | Moment Musical Op.94 (D.780) No.2 in A flat Major | Alfred Brendel

Nobody plays Schubert like Brendel.

Long Read of the Day

Operation Yellowhammer

Operation Yellowhammer was the government’s contingency planning for its response to the most severe anticipated short-term disruption under a no-deal Brexit – which is called the ‘reasonable worst case’ scenario. This interesting summary by the Institute for Government covered 12 key areas of risk, including food and water supplies, healthcare services, trade in goods and transport systems.

The really interesting thing about it, looking at it now, is how accurate it was.

Truly, we are governed by imbeciles. Not entirely surprising, given that the main criterion for membership of the Cabinet is to have been wrong about the biggest issue facing the UK since 1973.

Thanks to Janet Cobb for the link.

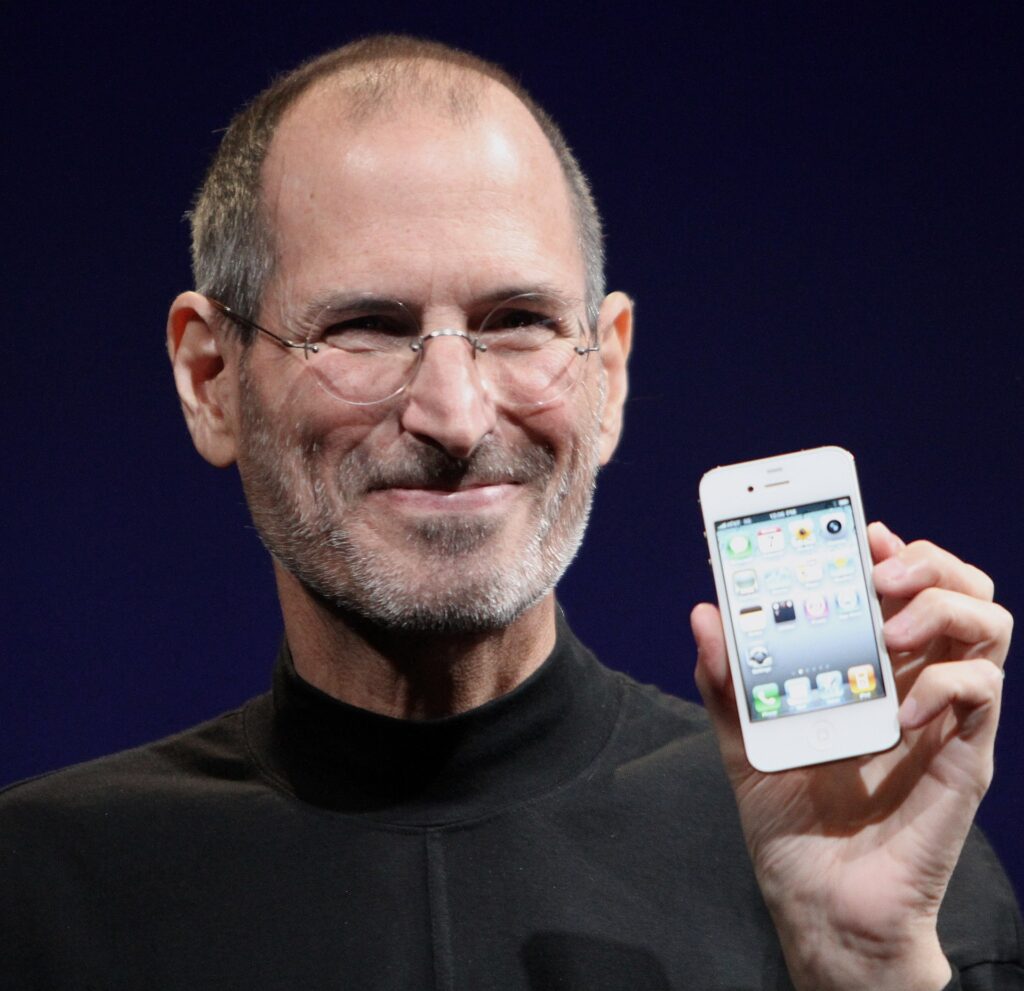

Takeaways from Frances Haugen’s star turn in Congress

She looks like a formidable whistleblower — as you can tell from Facebook’s scrambling to do damage limitation.

The NYT reporter came away with three ‘takeaways’:

- Republican and Democratic lawmakers are united on taking action to stop the harms caused to teenagers on Facebook.

- Lawmakers have gotten smarter about tech. (Hmmm… that wouldn’t have been hard, given their previous showings.)

- Facebook is sitting on an even larger mountain of internal research. (So there’s much more to be unearthed. Thie is rich subpoena territory.)

For his part, the Bloomberg reporter confessed that he was

”pleasantly surprised by how thoughtful the whistle-blower, Frances Haugen, was in her testimony and answers. I was even more surprised at how thoughtful our elected officials were in their questions.

The Hearing, he said, didn’t have the usual cadence of tech bosses hauled in to be shouted at by legislators looking for social-media soundbytes.

Tuesday’s hearing felt refreshingly different. The discussion primarily focused on Facebook’s actual problems, including its feed ranking algorithms, its impact on teens and CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s power. Haugen was helpful in understanding some of Facebook’s internal thinking, like its desire to reach teenagers because that’s the cohort it needs to maintain its growth.

She also helped identify major problems for future discussion, like the claim that Facebook’s efforts to fight misinformation predominantly center around English-language news, but most of its users don’t speak English. Haugen even offered up some potential solutions, like the idea of organizing user feeds based on the most recent posts, not a ranking algorithm. It’s not exactly a new idea, but it was an idea nonetheless.

Most importantly, it felt like a discussion, not a firing line.

(The Bloomberg stuff comes from their Fully Charged newsletter, for which I can never find a web-link.)

The Times had an interesting OpEd by Roddy Lindsay, a former Facebook data scientist who worked on the feed-curation algorithms and picked up on Ms Haugen’s view that those algorithms are one of the roots of Facebook’s societal toxicity.

When data scientists and software engineers blend content personalization and algorithmic amplification — as they do to produce Facebook’s News Feed, TikTok’s For You tab and YouTube’s recommendation engine — they create uncontrollable, attention-sucking beasts. Though these algorithms, such as Facebook’s “engagement-based ranking,” are marketed as increasing “relevant” content, they perpetuate biases and affect society in ways that are barely understood by their creators, much less users or regulators.

In 2007, I started working at Facebook as a data scientist, and my first assignment was to work on the algorithm used by News Feed. Facebook has had more than 15 years to demonstrate that algorithmic personal feeds can be built responsibly; if it hasn’t happened by now, it’s not going to happen. As Ms. Haugen said, it should now be humans, not computers, “facilitating who we get to hear from.”

I like the “attention-sucking beasts” metaphor, but while neutering said beasts would be useful, there’s no silver bullet for fixing corporations like Facebook.

As HL Mencken famously observed: “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong”.

Tech corporations are part of a bigger regulatory challenge, which we’re not even beginning to contemplate yet.

My Commonplace booklet

(Eh? See here)

-

A random conversation today about how smart women are often underestimated or ignored by dumber men reminded me of a lovely story about Cass Sunstein, the Uber-smart Harvard prof and Samantha Power, his equally smart wife. When she was Obama’s Ambassador to the UN, the couple lived in a suite in a fancy New York hotel when the UN was in session, and the staff immediately assumed that her husband was ‘Mr Power’. One morning he went down on his own to the lobby and asked the concierge to call him a cab. When the car arrived the concierge said “Your cab’s here, Mr Power.” At this point Cass said mildly, “Actually my name is Sunstein” — to which the concierge replied “Wow! You look just like Mr Power.”

-

My relay yesterday of criticisms of the UK electricity system by Greg Jackson, CEO of the disruptive supplier Octopus, did not impress one reader of this blog, who writes that he would be “a little more impressed with Mr Jackson if Octopus hadn’t just helped itself to all of my daughter-in-law’s salary to pay a fabricated bill for a fabricated meter – having told her only days previously that it recognised the meter was non-existent. Just the same tricks as the remainder of the “big six” – as regularly featured in the Guardian’s consumer column”.

Errata

Yesterday’s reference to Heather Cox ‘Robinson’ should have been to Heather Cox Richardson. And the link to the excerpt I quoted is https://heathercoxrichardson.substack.com/p/october-5-2021.

Many thanks to Jack Whyte for spotting it, and apologies to Professor Richardson for misnaming her.

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. And it’s free!