Quote of the Day

Another sign of Mr Trump’s interest in books came during the Black Lives Matter protests, when he appeared outside a Washington DC church holding a Bible. It was a deeply sinister move. And also a reminder to rewatch the interview where he claims the Bible is his favourite book but can’t seem to recall any verses. Asked whether he’s an “Old Testament guy or a News Testament guy”, he hesitates before replying “probably equal”. Evangelical Christians, you don’t have to vote for him.

- Henry Mance, Financial Times, 20/21 June, 2020

A Coronavirus Quiz

Below is a statement made by Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health, the House of Commons.

We have a clear four-part plan to respond to the outbreak of this disease: contain, delay, research and mitigate. We are taking all necessary measures to minimise the risk to the public. We have put in place enhanced monitoring measures at UK airports, and health information is available at all international airports, ports and international train stations. We have established a supported isolation facility at Heathrow to cater for international passengers who are tested, and to maximise infection control and free up NHS resources.

We are working closely with the World Health Organisation, the G7 and the wider international community to ensure that we are ready for all eventualities. We are co-ordinating research efforts with international partners. Our approach has at all times been guided by the chief medical officer, working on the basis of the best possible scientific evidence. The public can be assured that we have a clear plan to contain, delay, research and mitigate, and that we are working methodically through each step to keep the public safe.

Question: On what date was this statement made?

Answer: At the end of this day’s post.

The Covid-19 pandemic has offered advance sight of post-Brexit Britain.

Lovely FT column by Philip Stephens the other day.

“The mantra of Boris Johnson’s government”, he writes, “is that”,

unshackled from the EU, the nation will be “world-beating”. Free to make national choices and set its own scenery on the international stage, it will champion free trade from its own seat at the World Trade Organization and decide its own policies for global challenges such as climate change.

For Mr Johnson the pandemic was a chance for the UK to show its strengths and demonstrate what it could do in its new guise as a truly “sovereign” nation reborn as “Global Britain”. This explains perhaps his confidence when the outbreak began to take hold in early March. Back then, remember, Mr Johnson boasted of shaking hands with doctors during a hospital visit.

The bullish message from Downing Street recalled that Britain is home to some of the very best epidemiological scientists and research institutes: Johnson called them “world-leading”, in a variation on the his usual “world-beating” theme.

No government was better prepared. Britain had rehearsed for such an emergency in 2016 and stockpiled supplies. Exercise Cygnus, it was called. Of course, there also was the “fantastic” NHS. Britain would show the world how it was done.

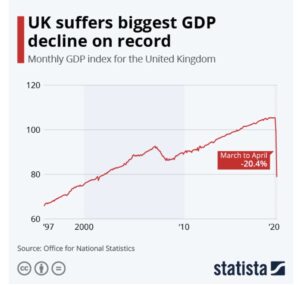

Unhappily, Covid-19 does not pay attention to theoretical notions of sovereignty or to national borders. Far from the best, Britain’s performance fighting the virus has been dismal, leaving it at the bottom of the league of comparable European states.

The problem is, says Stephens,

the yawning gap between assumed superiority and actual performance. Mr Johnson and his colleagues promote an image of Britain’s capabilities that is steeped in nostalgia for past greatness rather than shaped by contemporary appraisal. As one British diplomat puts it: “There is just an assumption that we do these things so much better than our European neighbours.”

The other lesson has been that sovereignty may provide the notional freedom to act, but that is not the same as the capacity to achieve national goals. Working outside the EU did not take Britain to the front of the queue in the scramble to secure medical supplies from China and India. So it will prove with post-Brexit trade deals.

Yep. The lack of UK state capacity revealed by the crisis is one of its most salutary lessons.

Deaths of despair

Atul Gawande has a long and absorbing essay in the New Yorker about Anne Case’s and Angus Deaton’s Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, a landmark investigation into why working-age white men and women without college degrees were dying from suicide, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related liver disease at such rates that, for three consecutive years, life expectancy for the U.S. population as a whole had fallen.

The surprise (for me anyway) is that this isn’t all about opioid addiction, though that plays a role. A key part of the answer, they maintain, is education — or, more accurately, the absence of it. Case and Deaton argue that the rise in deaths of despair is the consequence of the cumulative effect of a long economic stagnation and the way the US as a nation has dealt with it.

In the past four decades, Americans without bachelor’s degrees—the majority of the working-age population—have seen themselves become ever less valued in our economy. Their effort and experience provide smaller rewards than before, and they encounter longer periods between employment. It should come as no surprise that fewer continue to seek employment, and that more succumb to despair.

The problem isn’t that people are not the way they used to be. It’s that the economy and the structure of work are not the way they used to be. This has had devastating effects on the family and on community life. In 1980, rates of marriage by middle age were about eighty per cent for white people with and without bachelor’s degrees alike. As the economic prospects of those two groups have diverged, however, so have their marriage prospects. Today, about seventy-five per cent of college graduates are married by age forty-five, but only sixty per cent of non-college graduates are. Nonmarital childbearing has reached forty per cent among less educated white women. Parents without bachelor’s degrees are also now dramatically less likely to have a stable partner for rearing and financially supporting their children.

Unsurprisingly, one of the big factors they identify is the American healthcare system. The focus of their indictment is on the way that America’s health-care system is peculiarly reliant on employer-provided insurance. “As they show”, writes Gawande,

the premiums that employers pay amount to a perverse tax on hiring lower-skilled workers. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2019 the average family policy cost twenty-one thousand dollars, of which employers typically paid seventy per cent. “For a well-paid employee earning a salary of $150,000, the average family policy adds less than 10 percent to the cost of employing the worker,” Case and Deaton write. “For a low-wage worker on half the median wage, it is 60 percent.” Even as workers’ wages have stagnated or declined, then, the cost to their employers has risen sharply. One recent study shows that, between 1970 and 2016, the earnings that laborers received fell twenty-one per cent. But their total compensation, taken to include the cost of their benefits (in particular, health care), rose sixty-eight per cent. Increases in health-care costs have devoured take-home pay for those below the median income. At the same time, the system practically begs employers to reduce the number of less skilled workers they hire, by outsourcing or automating their positions. In Case and Deaton’s analysis, this makes American health care itself a prime cause of our rising death rates.

Their overall conclusion is that

capitalism, having failed America’s less educated workers for decades, must change, as it has in the past. “There have been previous periods when capitalism failed most people, as the Industrial Revolution got under way at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and again after the Great Depression,” they write. “But the beast was tamed, not slain.”

So the question from their work turns out to be the same question that is now everywhere: are we capable of again taming the beast?

Quarantine diary — Day 91

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!

Quiz Answer: Tuesday February 26, 2020 Hansard link