“One of the best short definitions of neoliberalism I have encountered is the one by Will Davies, namely, the dependence upon the strong state to pursue the disenchantment of politics by economics. If that sounds like an oxymoron, well, maybe that’s the nub of the project.”

Monthly Archives: December 2019

Democratic oversight?

Here’s my summary of what we learned from Ed Snowden’s revelations in 2013 and the official responses to them in Western democracies:

- There was astonishingly intensive and comprehensive state surveillance under inadequate democratic oversight in these democracies.

- There then followed various official and semi-official inquiries in the US, the UK and elsewhere.

- In some cases, these inquiries led to limited reforms. The US Oversight system remained broadly untouched. The UK had three separate inquiries, followed by a new Investigatory Powers Act, which enhanced some kinds of Judicial oversight, but also added new powers for the security services (e.g. ‘equipment interference’ and warrantless clickstream logging).

- The result: comprehensive state surveillance continues, under slightly less inadequate democratic oversight.

Now comes yesterday’s US Inspector General’s report into the FBI’s Russia investigation. It provides a peek under the hood of how the secret FISA Court process works, post-Snowden. “ At more than 400 pages”, says the New York Times, “the study amounted to the most searching look ever at the government’s secretive system for carrying out national-security surveillance on American soil. And what the report showed was not pretty”…

That’s putting it mildly. The Justice Department’s independent inspector general, Michael E. Horowitz, and his team uncovered a staggeringly dysfunctional and error-ridden process in how the F.B.I. went about obtaining and renewing court permission under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA, to wiretap Carter Page, a former Trump campaign adviser.

“The litany of problems with the Carter Page surveillance applications demonstrates how the secrecy shrouding the government’s one-sided FISA approval process breeds abuse,” said Hina Shamsi, the director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project. “The concerns the inspector general identifies apply to intrusive investigations of others, including especially Muslims, and far better safeguards against abuse are necessary.”

Congress enacted FISA in 1978 to regulate domestic surveillance for national-security investigations — monitoring suspected spies and terrorists, as opposed to ordinary criminals. Investigators must persuade a judge on a special court that a target is probably an agent of a foreign power. In 2018, there were 1,833 targets of such orders, including 232 Americans.

Most of those targets never learn that their privacy has been invaded, but some are sent to prison on the basis of evidence derived from the surveillance. And unlike in ordinary criminal wiretap cases, defendants are not permitted to see what investigators told the court about them to obtain permission to eavesdrop on their calls and emails.

According to the Times’s account, the inspector general found major errors, material omissions and unsupported statements about Mr. Page [the target of the surveillance] in the materials that went to the court. F.B.I. agents cherry-picked the evidence, telling the Justice Department information that made Mr. Page look suspicious and omitting material that cut the other way, and the department passed that misleading portrait onto the court.

Lots more in that vein. The surprising thing is that anybody should be surprised. That’s not to say that Carter was not a legitimate target for surveillance, by the way. But democracy dies in darkness.

Quote of the Day

”It is dumbfounding to observe how everyone suddenly reverts to being a strict nominalist when they encounter Neoliberalism. They circle round the word as if it were a dead animal in the middle of the road, crushed and distended, trying to figure out what to call it, even though, strictly speaking, they reserve judgment over whether it is really there.”

What the election is really about

Remarkable essay on openDemocracy by Anthony Barnett, who is recovering from major heart surgery. Here’s just one excerpt:

The determining issue may be Brexit. But Brexit has never been about Europe. Which is why its key advocate, who unbelievably is Prime Minister, is pitching his campaign on getting it “done” so we can focus on the “really important issues” that we face as a country. It’s a paradox Lewis Goodall tweeted neatly. After Brexit, way above all the other issues voters care about is the NHS. Once scorned by Johnson as a religion he now presents himself as its most zealous believer, while Jeremy Corbyn commits the last days of his campaign on the need to save it from Trump and privatisation.

Well, I’ve just experienced the very best of the NHS. I’ve also seen at first hand a culture which could open the way to undermining it. There is no doubting its fundamental magnificence. The heart of this is that it is driven by human need, not the profit motive or concern over costs. You know this the moment a hospital gets to work. I had an angiogram a few weeks before my operation. It’s a procedure where a nurse inserts a tiny catheter into your wrist and up through your arm’s artery until it gets near your heart. A dye is then injected which can be X-rayed so that specialists can assess the state of the blood vessels around the heart in advance of surgery. You are conscious throughout. Two people worked on my other wrist injecting blood thinners to ensure that the procedure itself does not trigger a heart attack or a stroke, and an emergency team is on hand in case it does. Along with radiographers, it meant there were eight people in scrubs in a gleaming operating theatre with a huge X-Ray machine and multiple screens, for this simple check-up. The ‘market’ cost of just this 20 minute procedure not to speak of the administrative outgoings of billing the charges would have been unspeakable. But it was needed, so it was done.

You don’t experience its cost-effectiveness in this. But others were coming in after me with conditions that were perhaps more complicated. With good management it is a very efficient use of the team that was in place. In the US, because of all the insurance, billing, and the disputes over charges, just the administrative costs of health care alone came to an estimated $496 billion in 2019. This is considerably more than the total expenditure on the NHS this year which was £143 billion.

The costs would have been far-greater for the surgery itself. But in my heart unit there were fellow patients from every class and walk of life, sharing a battlefield equality in our farting and groaning, as we were all treated equally with state-of-the-art operations, free from financial fear. The extraordinary human return means so much to our families we forget that elsewhere such a medical emergency could have bankrupted us. In the United States, between 2000 and 2012, over 40% of the nearly 10 million people diagnosed with cancer “depleted their entire life’s assets” to cover its treatment, according to the American Journal of Medicine. It’s not flippant to suggest that fear of such an outcome is itself enough to make you ill.

Well worth reading in full. I’ve never thought that Brexit is the key issue. In a way, it’s a kind of attempted coup d’etat by powerful political and economic interests (many of them foreign) to reshape the UK into a private-equity sandbox.

Linkblog

- The punishment of democracy Remarkable, insightful essay on the horrible election campaign to which the UK electorate is being subjected. Unmissable and wise.

- Impeach Trump. Save America. Tom Friedman on the urgency of the impeachment process. If Congress doesn’t do it, he argues, then the US will never again have a legitimate president. It’ll be back to de-facto monarchy.

- “Startups and Uncertainty” Long, thoughtful essay by Jerry Neumann on risk, uncertainty and what startups are really about.

- “This Guy Studies the ‘Global Systems Death Spiral’ That Might End Humanity” Could climate change get so bad that it leads to our extinction? A few researchers are trying to answer that question.

King Donald the First

Marvellous blast from Thomas Friedman: “Impeach Trump, save America”:

Folks, can you imagine what Russia’s President Putin is saying to himself today? “I can’t believe my luck! I not only got Trump to parrot my conspiracy theories, I got his whole party to do it! And for free! Who ever thought Americans would so easily sell out their own Constitution for one man? My God, I have Russian lawmakers in my own Parliament who’d quit before doing that. But it proves my point: America is no different from Russia, so spare me the lectures.”

If Congress were to do what Republicans demand — forgo impeaching this president for enlisting a foreign power to get him elected, after he refused to hand over any of the documents that Congress had requested and blocked all of his key aides who knew what happened from testifying — we would be saying that a president is henceforth above the law.

We would be saying that we no longer have three coequal branches of government. We would be saying that we no longer have a separation of powers.

We would be saying that our president is now a king.

Brings to mind the Benjamin Franklin’s reply to the question he was asked as he was leaving the Constitutional Convention in 1787: “Well, Doctor, what have we got — a Republic or a Monarchy?” “A Republic”, said Franklin, “if you can keep it.”

Looks like they can’t.

Linkblog

- Amazon Should Ban Auschwitz Ornaments, But Not Hitler’s Book Interesting argument by Tyler Cowen. “Where should a company such as Amazon.com Inc. draw the line when it comes to selling third-party merchandise? I propose a standard: Focus on whether the merchandise contributes to further understanding, one way or another, rather than whether it might embody evil.”

- Lovers in Auschwitz, Reunited 72 Years Later. He Had One Question. Amazing, heartwarming story.

- Larry and Sergey: a valediction A kind of living obituary of Google’s co-founders, who have stepped back into oblivion (while holding on to their shares).

- Startups and uncertainty Interesting (long) blog post by Jerry Neumann on risk, uncertainty and founding a company.

Fancy a job in Bletchley Park?

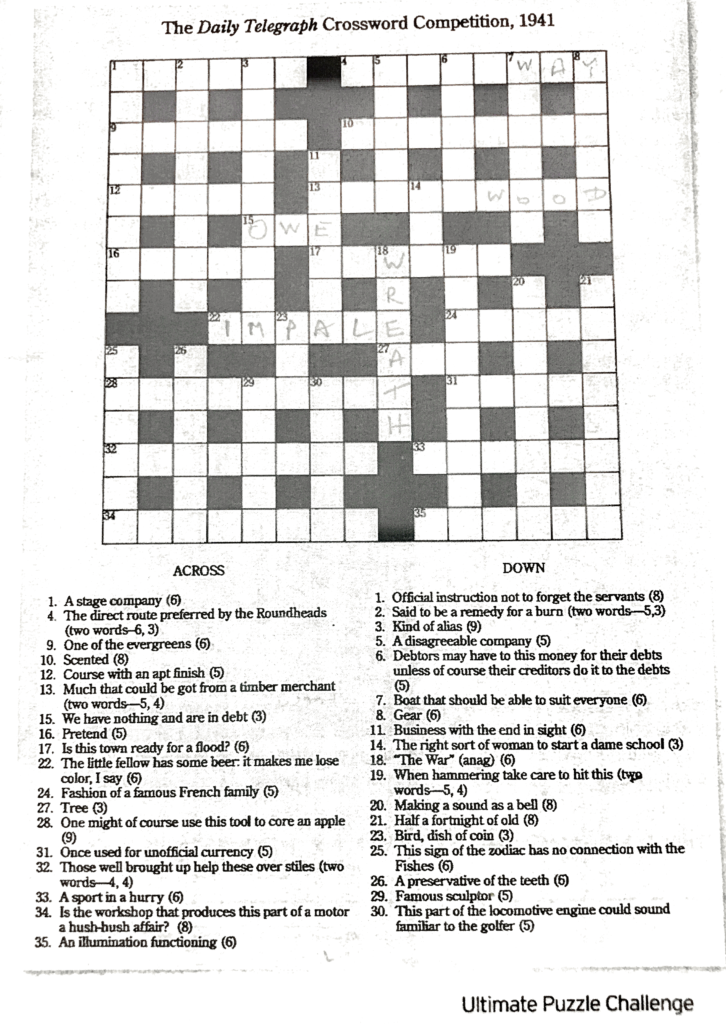

In late 1941, a mysterious Mr Gavin wrote to the Daily Telegraph offering £100 to be donated to charity if anyone could solve this crossword in less than 12 minutes. The competition was to be held at the Telegraph’s office in Fleet Street, London.

A few weeks later those who managed it received letters asking them to report to Military Intelligence (that well-known oxymoron), which then sent them on to Bletchley Park.

This recruitment method would never get past HR nowadays. But then, there was a war on.

(As you can see, someone in our house has been having a go at it!)

It’s different from the cryptic puzzles one finds nowadays in the posher newspapers — it’s a mixture of cryptic and quick clues.

A pandemic might do it

Interesting interview of Michael Lewis by Tim Adams in today’s Observer, talking about Lewis’s marvellous book, The Fifth Risk: Undoing Democracy about how the Trump Administration is dismantling or enfeebling vital bits of the administrative state. I particularly liked this segment:

Adams: Part of your story examines the consequences of the ideological cull of climate scientists from government. You have lived in close proximity to wildfires in California, there have been unprecedented hurricanes. Do you think there will come a point when people demand leaders who understand the importance of scientific knowledge?

Lewis: You would think so. It hasn’t happened yet. For people to suddenly start to value what good government does, I think there will have to be something that threatens a lot of people at once. The problem with a wildfire in California, or a hurricane in Florida, is that for most people it is happening to someone else. I think a pandemic might do it, something that could affect millions of people indiscriminately and from which you could not insulate yourself even if you were rich. I think that might do it.

Adams: That is quite an apocalyptic thought. You have always seemed by nature an optimist, are you feeling more nihilistic about what you call the drift of things?

Lewis: I’m a little more wary than I have been. What we are seeing is an attack on the idea of progress and the idea of science. In the Trump administration there seems to be a total lack of respect for expertise. It sounds like you have something of the same with Boris Johnson. For this kind of attack to work you need to have characters who don’t care at all about consequences.

The myth of American competitiveness

Most of the complacent guff about how American capitalism is better than its counterparts in other parts of the world is just that — guff.

The economist Thomas Philippon has done a terrific, data-intensive demolition job on the myth. In The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets he shows that America is no longer the spiritual home of the free-market economy (any more than Westminster is now “the mother of Parliaments”). Competition there is not fiercer than it is in ‘old’ Europe. Its regulators have been asleep at the wheel for decades and its latest crop of giant companies are not all that different from their predecessors.

Or, as he puts it:

”First, US markets have become less competitive: concentration is high in many industries, leaders are entrenched, and their profit rates are excessive. Second, this lack of competition has hurt consumers and workers: it has led to higher prices, lower investment and lower productivity growth. Third, and contrary to popular wisdom, the main explanation is political, not technological: I have traced the decrease in competition to increasing barriers to entry and weak antitrust enforcement, sustained by heavy lobbying and campaign contributions.”

So next time some tech evangelist starts to rant on about how backward Europe is, the appropriate reply is: give me a break.