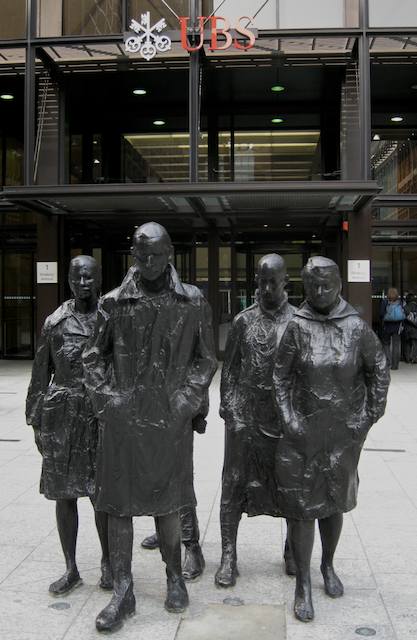

Broadgate, City of London, Monday. Flickr version here.

Daily Archives: April 7, 2009

Seeing all the angles

In the Bloomberg Gallery, Finsbury Square. Flickr version here.

“Misappropriation” vs. Fair Use

The legal basis for a challenge by newspapers to Google is beginning to emerge.

In 1918, the AP was involved in a case called International News Service v. Associated Press. Like current competitor All Headline, INS didn’t actually copy AP’artime scoops off the wire, have a hired hack rewrite the story in his own words, and put out their own version of the breaking news without having to bear all the overhead (not to mention the considerable risk) of sending trained reporters to a war zone. It wasn’t quite copyright infringement, but it sufficiently offended the justices’ sense of fair play that they developed the doctrine of ‘misappropriation’ to cover the immediate copying and dissemination of ‘hot news’ by commercial competitors of a news organization. If such ‘free riding’ were allowed, the judges reasoned, the parasites would always be able to undersell their hosts, to the detriment of journalism in the long run.

It’s not hard to see why AP is concerned now. According to its annual report (PDF), the combination of subscriber attrition and the lower fees they’ve had to adopt to keep that dwindling, cash-strapped client base on board “will result in a revenue decline not seen by the company since the Great Depression.”

The Internet compounds the problem. The RIAA and MPAA can at least try—however ineffectively—to use copyright law to stanch unauthorized copying of their works. But what AP is selling isn’t really the scintillating prose of its writers: it’s fast access to the facts of breaking news. Now, though, a writer for any one of a million websites can read an AP story on the site of a subscribing news organization, write up their own paraphrase of the story, and have it posted—and drawing eyeballs from AP subscribers — within an hour of the original’s going live.

This might just work for AP. It’ll be harder for newspapers to argue, however — except for straight news coverage. I’d be surprised if they could make the argument stick for commentary — which, after all, is what most newspapers do nowadays.

Forty years on

Today is the 40th anniversary of the first Request For Comment (RFC) — the form devised by the ARPANET’s designers for discussing technical issues. Steve Crocker — who as a graduate student invented the idea — has written a lovely piece about it in the New York Times:

A great deal of deliberation and planning had gone into the network’s underlying technology, but no one had given a lot of thought to what we would actually do with it. So, in August 1968, a handful of graduate students and staff members from the four sites began meeting intermittently, in person, to try to figure it out. (I was lucky enough to be one of the U.C.L.A. students included in these wide-ranging discussions.) It wasn’t until the next spring that we realized we should start writing down our thoughts. We thought maybe we’d put together a few temporary, informal memos on network protocols, the rules by which computers exchange information. I offered to organize our early notes.

What was supposed to be a simple chore turned out to be a nerve-racking project. Our intent was only to encourage others to chime in, but I worried we might sound as though we were making official decisions or asserting authority. In my mind, I was inciting the wrath of some prestigious professor at some phantom East Coast establishment. I was actually losing sleep over the whole thing, and when I finally tackled my first memo, which dealt with basic communication between two computers, it was in the wee hours of the morning. I had to work in a bathroom so as not to disturb the friends I was staying with, who were all asleep.

Still fearful of sounding presumptuous, I labeled the note a “Request for Comments.” R.F.C. 1, written 40 years ago today, left many questions unanswered, and soon became obsolete. But the R.F.C.’s themselves took root and flourished. They became the formal method of publishing Internet protocol standards, and today there are more than 5,000, all readily available online.

But we started writing these notes before we had e-mail, or even before the network was really working, so we wrote our visions for the future on paper and sent them around via the postal service. We’d mail each research group one printout and they’d have to photocopy more themselves.

The early R.F.C.’s ranged from grand visions to mundane details, although the latter quickly became the most common. Less important than the content of those first documents was that they were available free of charge and anyone could write one. Instead of authority-based decision-making, we relied on a process we called “rough consensus and running code.” Everyone was welcome to propose ideas, and if enough people liked it and used it, the design became a standard…

The RFC archive is here.

Relationship Symmetry in Social Networks

Interesting analysis by Joshua Porter of the difference between Twitter and FaceBook.

In general, there are two ways to model human relationships in software. An “asymmetric” model is how Twitter currently works. You can “follow” someone else without them following you back. It’s a one-way relationship that may or may not be mutual.

Relationship Symmetry in the Facebook model

Facebook, on the other hand, has always used a “symmetric” model, where each time you add someone as a friend they have to add you as a friend as well. This is a two-way relationship, and it is required to have any relationship at all. So as a Facebook user there is always a 1-1 relationship among your friends. Everyone who you have claimed as a friend has also claimed you as a friend.

The post goes on to cite Andrew Chen’s point that Twitter allows 4 types of relationships, while Facebook only allows for two. The two relationships of Facebook are “friend and Not Friend”. The four relationships of Twitter are:

1. People who follow you, but you don’t follow back

2. People who don’t follow you, but you follow them

3. You both follow each other (Friends!)

4. Neither of you follow each other

As Andrew points out, an asymmetric model allows for more types of relationships. I think the benefits go further than that. I think that the asymmetric model better mimics how real attention works…and how it has always worked.