Photographed outside a coach stop in Donegal.

Photographed outside a coach stop in Donegal.

Seeking to catch up on reading over the holidays, I took some back issues of the London Review of Books with me. I was particularly taken by “Looking for someone to kill”, one of Patrick Cockburn’s grimly realistic dispatches from Baghdad. I admire Cockburn’s journalism — he and Robert Fisk seem to me to be the best Western journalists writing about the Middle East. I’m also interested in him because I met him once or twice, and because his parents, Claud and Patricia, had been very nice to me when I was an undergraduate in Cork in the 1960s.

Later that day, we went to Donegal in search of more reading material for the kids, and wound up in the Four Masters bookshop on the Diamond, a small shop which has an interesting range of books for sale. It carries, of course, the usual beach-thrillers by Grisham etc., but also stuff (Seamus Heaney’s collected prose essays, Roy Foster’s mega-bio of WB Yeats, Andrew Marr’s lovely book on journalism etc.) which implies a discriminating and quirky owner.

Up on the top shelf I found Patrick’s autobiography, The Broken Boy.

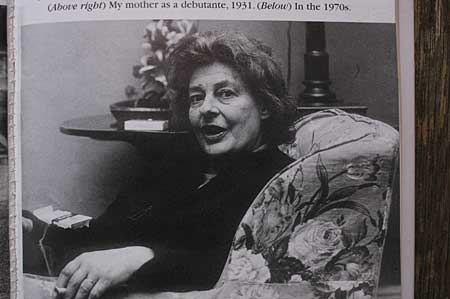

The title comes from the fact that Patrick contracted polio at the age of six, and still bears the scars of it. (Which makes his ability to report from some of the most terrifying places on earth all the more remarkable.) So of course I reached up and took it down. The book fell open at a page showing this photograph.

I recognised it immediately as one of mine — I took it in the 1970s when visiting Claud and Patricia in their home in Youghal when I was back from Cambridge. It was lovely to see it used to such good effect, because it captures something of her remarkable spirit.

Claud was one of my heroes, and he and Patricia were immensely welcoming and tolerant of the hotheaded and opinionated would-be journalist who sought their company in the Sixties. I’ve never forgotten Claud’s advice to me when I told him I’d like to try journalism after Cambridge. “Make sure you libel someone important early in your career”, were his parting words. As a TV critic in the 1980s and 1990s, I did my best to live up to it (and enriched some lawyers as a result)!

This morning’s Observer column on the perennial mystery of why people continue using software that causes them so much grief. Sample:

When friends and family tell me their woeful stories of viruses and worms, I have learnt to bite my tongue and make sympathetic, but incoherent noises. This was not how I used to react. Once upon a time I would say, in a smugly superior way, that if people would insist on supping with the devil then they should expect to get scorched; and if they wished to get off this torture-rack then they should move to a different – Apple or Linux – platform.

But I rapidly learnt this was not what these wretches want to hear. They do not want to be told that they should abandon their Microsoft-ridden machines and worship in a different church. So in the end, I stopped telling them about Apple and Linux and began mouthing the soothing bromides favoured by vicars when dealing with terminal cases.

En passant… This religious dimension brings to mind Umberto Eco’s wonderful essay on the difference between the Apple Mac and the IBM PC, of which the nub reads…

The fact is that the world is divided between users of the Macintosh computer and users of MS-DOS compatible computers. I am firmly of the opinion that the Macintosh is Catholic and that DOS is Protestant. Indeed, the Macintosh is counter-reformist and has been influenced by the ratio studiorum of the Jesuits. It is cheerful, friendly, conciliatory; it tells the faithful how they must proceed step by step to reach — if not the kingdom of Heaven — the moment in which their document is printed. It is catechistic: The essence of revelation is dealt with via simple formulae and sumptuous icons. Everyone has a right to salvation.

DOS is Protestant, or even Calvinistic. It allows free interpretation of scripture, demands difficult personal decisions, imposes a subtle hermeneutics upon the user, and takes for granted the idea that not all can achieve salvation. To make the system work you need to interpret the program yourself: Far away from the baroque community of revelers, the user is closed within the loneliness of his own inner torment.