This morning’s Observer column. From the headline I’m not convinced that the sub-editors spotted the irony.

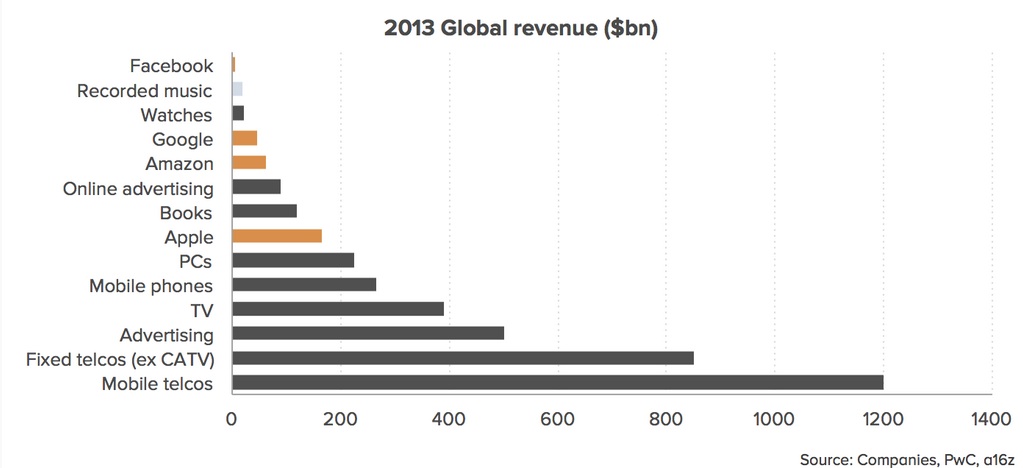

Like I said, everybody who is anybody in the tech business is very turned on by the IoT. It’s going to make lots of money – oh, and it’ll change the world, too. Of course there are some boring old creeps who keep raining on the parade. Spoilsports, I call them. There are, for example, the “security” experts who think that the IoT opens up horrendous vulnerabilities for our networked society. Hackers in Azerbaijan could get control of our “smart” electricity meters and shut down the whole of East Anglia with the click of a mouse. Pshaw! As if the folks in Azerbaijan even knew there was such a place as East Anglia. Or some guy in Anonymous could remotely jam the accelerator in your car so that you drive into your garage at 130mph even when you have your foot firmly on the brake. As if!

That’s why it’s *sooo* annoying when the media publicise scare stories about security lapses involving connected gadgets. I mean to say, how could TRENDnet have known that its “secure” security webcams weren’t really secure at all? It’s not its fault that a hacker broke into the SecurView camera software and told other people how to do it. The result, according to the US Federal Trade Commission, was that “hackers posted links to the live feeds of nearly 700 of the cameras. The feeds displayed babies asleep in their cribs, young children playing and adults going about their daily lives”.

This is *so* unfair. Poor old TRENDnet makes security *cameras*. Why should it know anything about internet security?