Hmmm… Just discovered that I have over 3,000 followers on Twitter. I will have to behave responsibly. Sigh.

Category Archives: Social Networking

Social physics and the Oscars

The idea that Google searches, tweets and Facebook ‘likes’ can be useful predictors of trends, developments and movie ‘hits’ has captured the imagination of many hucksters and media ‘analysts’. For example, it seems that Google searches may be good predictors of influenza outbreaks. And some time ago there was an interesting paper by Sitaram Asur and Bernardo in which they analyzed 2.89 million tweets from 1.2 million users about 24 movies released over a three-month period. They concluded that the rate of Tweets could predict the success of movies prior to their release, and also spot sleeper movies that grew successful over time. They also concluded that the quality of the predictions was significantly better than any other measure such as the Hollywood Stock Exchange.

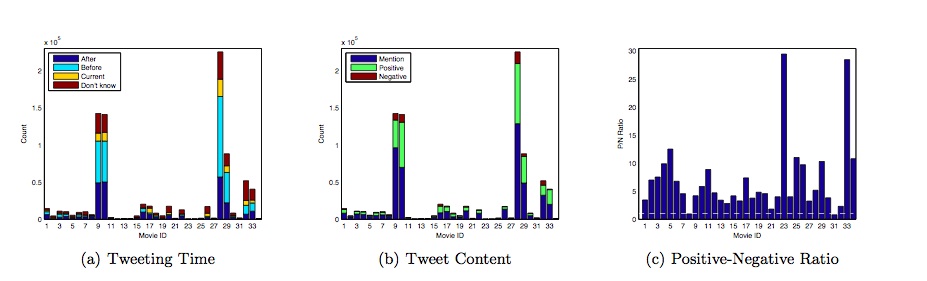

These findings seemed plausible to me. After all, if a large number of people are sharing thoughts about something (or expressing concerns via Google searches), then it would be reasonable to infer that data-mining will yield useful information. But now an interesting new study by some Princeton researchers suggests that a certain amount of scepticism might be in order. In a paper entitled “Why Watching Movie Tweets Won’t Tell the Whole Story?” [it’s not clear what the question-mark implies] Felix Ming Fai Wong, Soumya Sen and Mung Chiang question the idea that Twitter is a reliable predictor of the future, at least as far as winning Oscars and predicgint box office revenue are concerned. They collected 12 million tweets between February 2 and March 12 by tracking keywords related to recently-released or Oscar-nominated movies, classified them by relevance, sentiment and temporal context and analysed them for positive or negative sentiment. They then compared the resulting opinion statistics with sentiment about the same movies obtained from two conventional online review sites — iMDB and Rotten Tomatoes.

Their conclusions are interesting. They found that Twitter users are more likely to post positive views than negatives ones, and that views on Twitter do not necessarily correlate with those from the conventional sites. And — unlike Asur and Huberman — they seem unconvinced that Twitter sentiment is a good predictor of box-office revenue.

I suppose the only real conclusion to be drawn from this is that data-mining and “social physics” are not exact sciences. But then, we knew that anyway. Didn’t we?

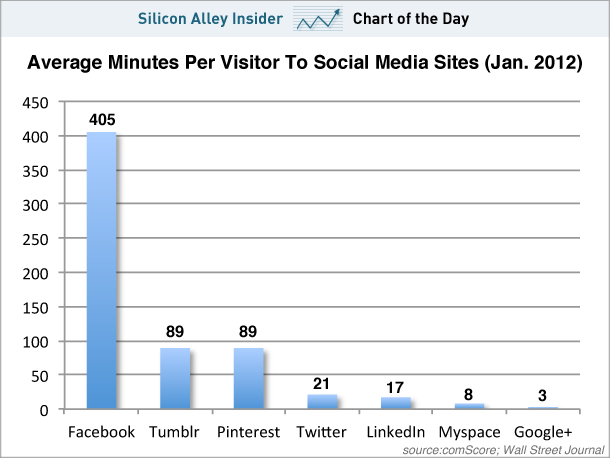

So that’s why nobody is getting any work done…

Baron Zuckerberg: the Haussmann of the Internet

This morning’s Observer column.

In Morozov’s view, something similar has happened to the internet. It’s no longer a place for strolling – it’s a place for getting things done. “Hardly anyone ‘surfs’ the web any more.” Mobile apps, which bypass most of the internet, make cyberflânerie less likely. And much of today’s online activity revolves around shopping. “Strolling through Groupon isn’t as much fun as strolling through an arcade, online or off.”

So Amazon is the equivalent of La Samaritaine – a place you go to buy stuff. And Facebook? Ah well, says Morozov, Zuckerberg wants to wipe out the individualism that was at the heart of flânerie. He wants everything to be “social”. “Do you want to go to the movies by yourself,” he asked recently, “or do you want to go to the movies with your friends?” His answer: “You want to go with your friends.” My answer: I’ll go by myself, thank you. But then I’m so 19th century.

Footnote: Earlier in the column I mentioned Newton’s First Law, a reference which prompted this lovely email from a reader:

“Sorry to be so pedantic, but when you mentioned Newton’s first law I think you had his third in mind. The third law states: the mutual forces of action and reaction between two bodies are equal, opposite and co-linear. (The law is usually imprecisely stated: for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.) How do I know? Well, I spent most of my working life teaching engineering dynamics at graduate and post-graduate level.”

Real hero of the Facebook story isn’t Zuckerberg

My take on the Facebook story — from yesterday’s Observer.

The number to watch is not the putative $100bn valuation but the 845 million users that Facebook now claims to have. The observation that if Facebook were a country then it would be the third most populous on the planet has become a cliche, but underpinning it is an intriguing question: how did an idea cooked up in a Harvard dorm become so powerful?

Thanks to a compelling movie, The Social Network, we think we know the story. A ferociously gifted Harvard sophomore named Zuckerberg has difficulties with women and vents his frustration by creating an offensive web application that invites users to compare pairs of female students and indicate which is “hottest”. He puts this up on the Harvard network where it gets him into trouble with the authorities. Then he lifts an idea from a pair of nice-but-dim Wasp contemporaries who need a programmer and, in a frenzied burst of inspired hacking, implements the idea in computer code, thereby creating an online version of the printed “facebooks” common to elite US universities. This he then launches on an unsuspecting world. The Wasps sue him but lose (though get a settlement). Zuckerberg goes on to become Master of the Universe. Cue music, fade to black.

It’s all true, sort of, but the dramatic imperatives of the narrative obscure the really significant bit of the story. So let’s rewind…

Facebook and the sociopathic mindset

This morning’s Observer column.

The truth is that companies such as Facebook are basically the corporate world’s equivalent of sociopaths, that is to say individuals who are completely lacking in conscience and respect for others. In her book The Sociopath Next Door, Martha Stout of Harvard medical school tries to convey what goes on in the mind of such an individual. “Imagine,” she writes, “not having a conscience, none at all, no feelings of guilt or remorse no matter what you do, no limiting sense of concern of the wellbeing of strangers, friends, or even family members. Imagine no struggles with shame, not a single one in your whole life, no matter what kind of selfish, lazy, harmful, or immoral action you had taken. And pretend that the concept of responsibility is unknown to you, except as a burden others seem to accept without question, like gullible fools.”

Welcome to the Facebook mindset.

Social media explained

The First Law of Internet services: no free lunch

This morning’s Observer column.

Physics has Newton’s first law (“Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed”). The equivalent for internet services is simpler, though just as general in its applicability: it says that there is no such thing as a free lunch.

The strange thing is that most users of Google, Facebook, Twitter and other “free” services seem to be only dimly aware of this law…

Facebook and its digital sharecroppers

Terrific Guardian piece by Adrian Short. Excerpt:

When you use a free web service you’re the underclass. At best you’re a guest. At worst you’re a beggar, couchsurfing the web and scavenging for crumbs. It’s a cliché but worth repeating: if you’re not paying for it, you’re aren’t the customer, you’re the product. Your individual account is probably worth very little to the service provider, so they’ll have no qualms whatsoever with tinkering with the service or even making radical changes in their interests rather than yours. If you don’t like it you’re welcome to leave. You may well not be able to take your content and data with you, and even if you can, all your URLs will be broken.

The conclusion here should be obvious: if you really care about your site you need to run it on your own domain. You need to own your URLs. You’ll have total control and no-one can take it away from you. You don’t need anyone else. If you put the effort in up front it’ll pay off in the long run.

But it’s no longer that simple…

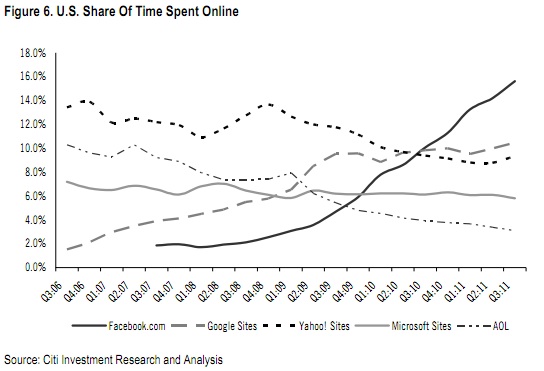

Why an increasing number of people think that Facebook is the Internet

Chapter Two of my forthcoming book is entitled “The Web is not the Net”. It’s there because I was alarmed by the number of people who thought that the Web and the Internet were synonomous. When I mentioned this to Tim Berners-Lee at a Royal Society symposium he said that the situation was even worse than that: millions of people now think that Facebook is the Internet. This chart (via Peter Kafka) from a report by Citigroup Analyst Mark Mahaney illustrates the extent of the problem.