Category Archives: Social Networking

Facebook: the unique self-disrupting machine?

Interesting post by M.G. Siegler:

Reading over the coverage of F8 this week, one thing is clear: Facebook the social network isn’t very interesting anymore. I think we’re on the other side of its peak, even if we can’t perceive that just yet. The interesting parts of Facebook are now Messenger, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Oculus.

They are slowly becoming Facebook. A federation of products, not the social networking stream.

I think we’ll look back and believe that Facebook, like Apple, is a company that did a great job disrupting itself before others could. And they did it all through smart acquisitions — people forget that even Messenger was an acquisition way back when. Just imagine if they had been able to buy Snapchat as well…

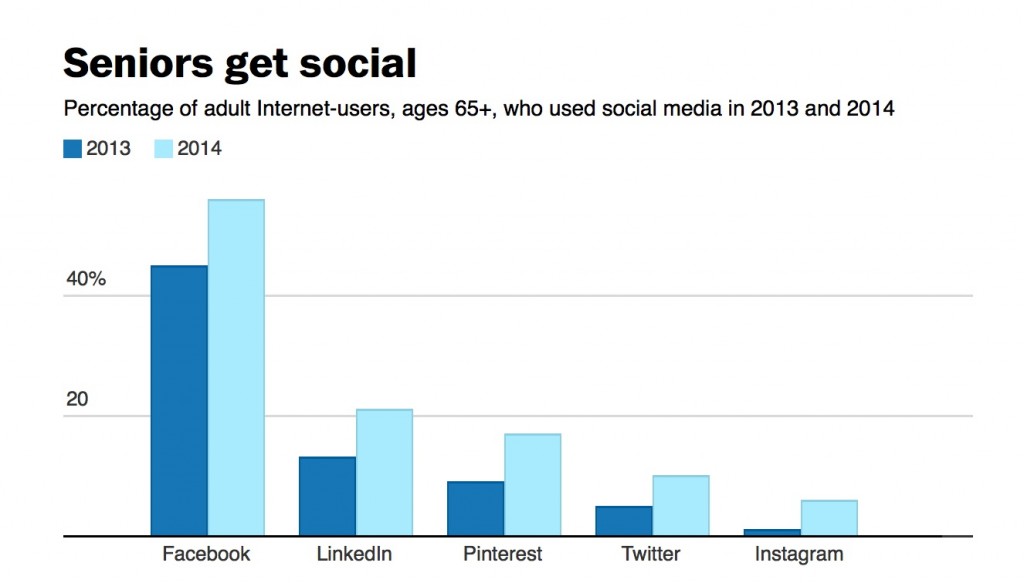

Facebook’s ageing population

Facebook moves in on LinkedIn

Well, well. According to this BBC story (which itself is based on a Financial Times story), Facebook is moving in on LinkedIn’s territory:

Facebook is building a network for professionals to connect and collaborate on work-related documents, the Financial Times reports.

Facebook at Work will look similar to its existing social network, but users will be able to keep their personal profiles separate, the paper says.

They also would be able to chat with colleagues, build professional networks and share documents, people said to be working on it told the Financial Times.

This is a difficult one for some of us. I mean to say, I loathe and detest LinkedIn, which I think is one of the most obnoxious ‘social’ networks I’ve seen. On the other hand, I’m not too enamoured of Facebook either. But I’m not surprised that LinkedIn’s shares were down today after the news broke.

In a more detached frame of mind, there might be something interesting here in terms of network theory. For example, are the ties that bind Facebook users stronger or weaker than those that link LinkedIn users?

Why Facebook is for ice buckets and Twitter is for what’s actually going on

Tomorrow’s Observer column

Ferguson is a predominantly black town, but its police force is predominantly white. Shortly after the killing, bystanders were recording eyewitness interviews and protests on smartphones and linking to the resulting footage from their Twitter accounts. News of the killing spread like wildfire across the US, leading to days of street confrontations between protesters and police and the imposition of something very like martial law. The US attorney general eventually turned up and the FBI opened a civil rights investigation. For days, if you were a Twitter user, Ferguson dominated your tweetstream, to the point where one of my acquaintances, returning from a holiday off the grid, initially inferred from the trending hashtag “#ferguson” that Sir Alex had died.

There’s no doubt that Twitter played a key role in elevating a local killing into national and international news. (Even Putin’s staff had some fun with it, offering to send human rights observers.) More than 3.6m Ferguson-related tweets were sent between 9 August, the day Brown was killed, and 17 August.

Three cheers for social media, then?

Not quite. ..

Sometimes, the camera doesn’t lie

This is fascinating. It’s also rather embarrassing for the Kremlin.

Selfies taken by Russian soldier Alexander Sotkin appear to provide damming evidence that Russian forces have been operating in Ukraine. Sotkin posted a number of images on social networking site instagram, apparently without realising that they were being geotagged to reveal his location when he took them.

Facebook, ethics and us, its hapless (and hypocritical?) users

This morning’s Observer column about the Facebook ’emotional contagion’ experiment.

The arguments about whether the experiment was unethical reveal the extent to which big data is changing our regulatory landscape. Many of the activities that large-scale data analytics now make possible are undoubtedly “legal” simply because our laws are so far behind the curve. Our data-protection regimes protect specific types of personal information, but data analytics enables corporations and governments to build up very revealing information “mosaics” about individuals by assembling large numbers of the digital traces that we all leave in cyberspace. And none of those traces has legal protection at the moment.

Besides, the idea that corporations might behave ethically is as absurd as the proposition that cats should respect the rights of small mammals. Cats do what cats do: kill other creatures. Corporations do what corporations do: maximise revenues and shareholder value and stay within the law. Facebook may be on the extreme end of corporate sociopathy, but really it’s just the exception that proves the rule.

danah boyd has a typically insightful blog post about this.

She points out that there are all kinds of undiscussed contradictions in this stuff. Most if not all of the media business (off- and online) involves trying to influence people’s emotions, but we rarely talk about this. But when an online company does it, and explains why, then there’s a row.

Facebook actively alters the content you see. Most people focus on the practice of marketing, but most of what Facebook’s algorithms do involve curating content to provide you with what they think you want to see. Facebook algorithmically determines which of your friends’ posts you see. They don’t do this for marketing reasons. They do this because they want you to want to come back to the site day after day. They want you to be happy. They don’t want you to be overwhelmed. Their everyday algorithms are meant to manipulate your emotions. What factors go into this? We don’t know.

But…

Facebook is not alone in algorithmically predicting what content you wish to see. Any recommendation system or curatorial system is prioritizing some content over others. But let’s compare what we glean from this study with standard practice. Most sites, from major news media to social media, have some algorithm that shows you the content that people click on the most. This is what drives media entities to produce listicals, flashy headlines, and car crash news stories. What do you think garners more traffic – a detailed analysis of what’s happening in Syria or 29 pictures of the cutest members of the animal kingdom? Part of what media learned long ago is that fear and salacious gossip sell papers. 4chan taught us that grotesque imagery and cute kittens work too. What this means online is that stories about child abductions, dangerous islands filled with snakes, and celebrity sex tape scandals are often the most clicked on, retweeted, favorited, etc. So an entire industry has emerged to produce crappy click bait content under the banner of “news.”

Guess what? When people are surrounded by fear-mongering news media, they get anxious. They fear the wrong things. Moral panics emerge. And yet, we as a society believe that it’s totally acceptable for news media – and its click bait brethren – to manipulate people’s emotions through the headlines they produce and the content they cover. And we generally accept that algorithmic curators are perfectly well within their right to prioritize that heavily clicked content over others, regardless of the psychological toll on individuals or the society. What makes their practice different? (Other than the fact that the media wouldn’t hold itself accountable for its own manipulative practices…)

Somehow, shrugging our shoulders and saying that we promoted content because it was popular is acceptable because those actors don’t voice that their intention is to manipulate your emotions so that you keep viewing their reporting and advertisements. And it’s also acceptable to manipulate people for advertising because that’s just business. But when researchers admit that they’re trying to learn if they can manipulate people’s emotions, they’re shunned. What this suggests is that the practice is acceptable, but admitting the intention and being transparent about the process is not.

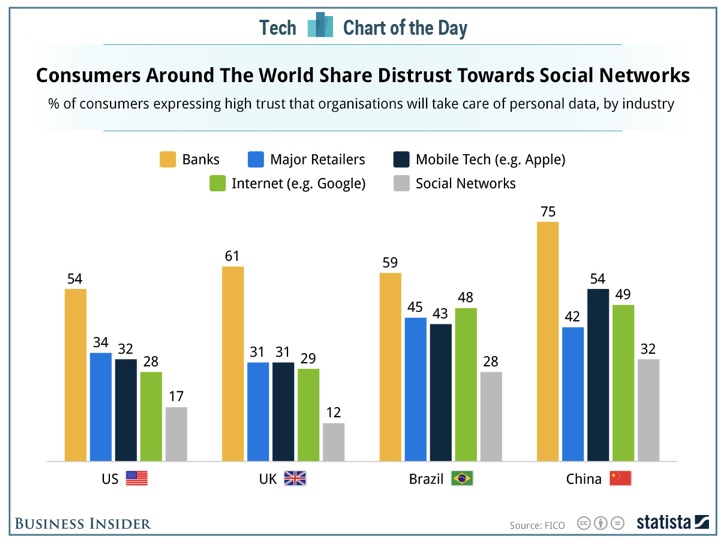

Who do you trust?

The Laws of Social Networking

There is a 100/10/1 “rule of thumb” with social services. 1% will create content, 10% will engage with it, and 100% will consume it. If only 10% of your users need to log in because 90% just want to consume, then you’ll end up with the vast majority of your users in the logged out camp. Don’t ignore them, build services for them, and you can slowly but surely lead them to more engagement and potentially some day into the logged in camp.

Metcalfe’s Law Rules OK

This morning’s Observer column:

There are two paradoxical things about Twitter. The first is how so many people apparently can’t get their heads around what seems like a blindingly simple idea – free expression, 140 characters at a time. I long ago lost count of the number of people who would come up to me on social occasions saying that they just couldn’t see the point of Twitter. Why would anyone be interested in knowing what they had for breakfast? I would patiently explain that while some twitterers might indeed be broadcasting details of their eating habits, the significance of the medium was that it enabled one to tap into the “thought-stream” of interesting individuals. The key to it, in other words, lay in choosing whom to “follow”. In that way, Twitter functions as a human-mediated RSS feed which is why, IMHO, it continues to be one of the most useful services available on the internet.

The second paradox about Twitter is how a service that has become ubiquitous – and enjoys nearly 100% name recognition, at least in industrialised countries – could become the stuff of analysts’ nightmares because they fear it lacks a business model that will one day produce the revenues to justify investors’ hopes for it.

They may be right about the business model – in which case Twitter becomes a perfect case study in the economics of information goods. The key to success in cyberspace is to harness the power of Metcalfe’s Law, which says that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of its users…