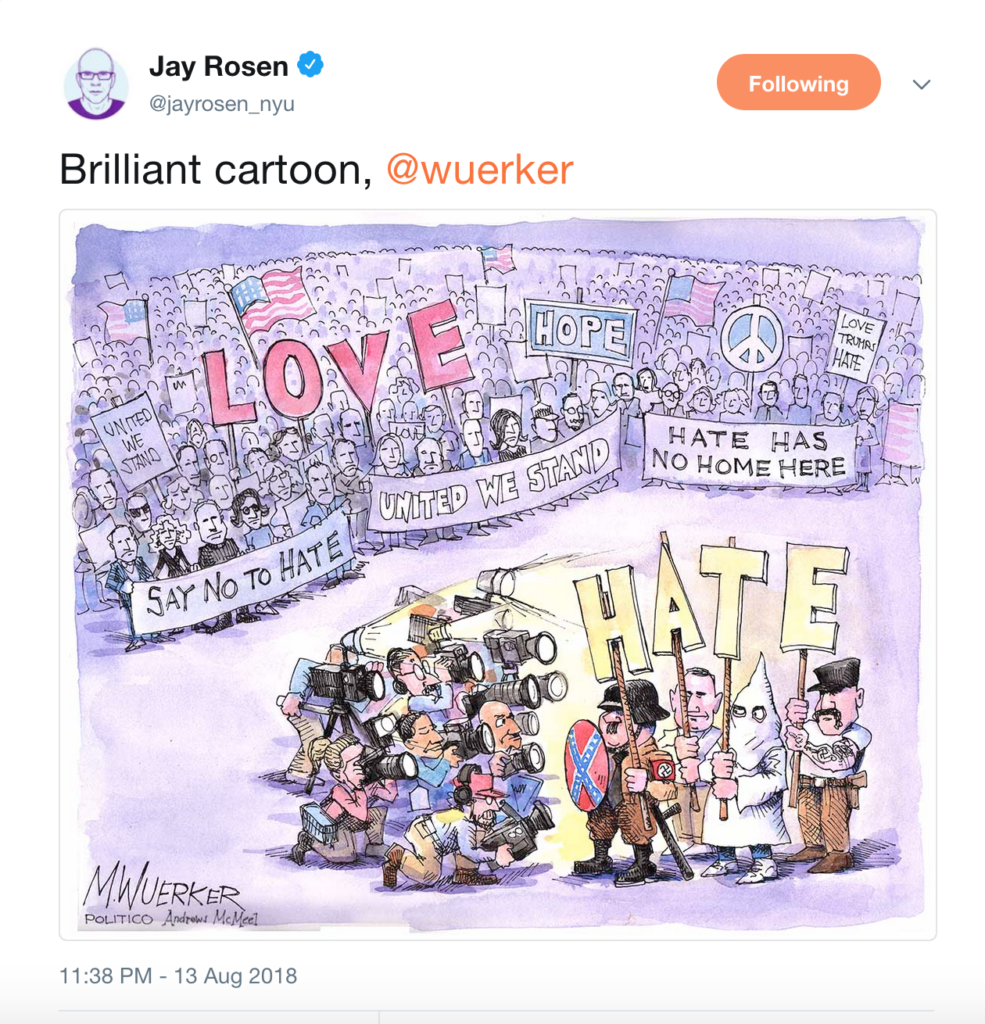

After all the alt-right demonstration scheduled for Washington D.C. to mark the first anniversary of Charlottesville turned out to be a damp squib.

Category Archives: Politics

Context, not content, is what’s needed now. And collaboration, not competition.

From a striking CJR post by Todd Gitlin:

After months of recalculation, of reappraisals agonizing and not, of euphemisms and of mea culpas loud and soft, the Times does not know with whom it is dealing. It is as if the mafia were being approached as a quaint bunch of oddballs. It’s as if oversight were the most plausible reason why the famous Rob Goldstone email addressed to Donald J. Trump, Jr., subject-lined “Russia – Clinton – private and confidential,” failed to “set off alarm bells” among the likes of Paul Manafort, Jared Kushner, and Trump Jr. in Trump Tower—and not the far more plausible explanation that Russian cronies were nothing new at making approaches to Trumpworld. Trump’s buildings were homes away from home for all manner of criminals and Russian investors, as were his foreign ventures.

This is what journalists called “context.” Call it background, call it whatever you want. But if you ignore it, you are reporting a baseball game as if people in uniforms are running around a diamond and chasing a ball for no apparent reason at all.

Yep. This essay goes nicely with Dan Gilmor’s plea for journalists to get their acts together on reporting Trump. There’s a strange way in which the competitiveness of journalists is preventing them from collaborating to fight Trump’s campaign to sideline the First Amendment.

That means breaking with customs, and some traditions — changing the journalism, and some of the ways you practice it, to cope with the onslaught of willful misinformation aimed at undermining public belief in basic reality. You can start by looking at the public’s information needs from the public’s point of view, not just your own.

The collaboration needs to be broad, and deep, across organizations and platforms. It can be immediate — such as an agreement among White House reporters to resist the marginalizing, or banning outright, of journalists who displease the president. If a legitimate reporter is banned from an event, or verbally dismissed in a briefing or press conference, other journalists should either boycott the event or, at the very least, ask and re-ask his or her question until it’s answered. In the briefing room, show some spine, and do it together.

The trouble is: most journalists are not by instinct collaborative — which is why they find networked journalism difficult. And their employers are rarely helpful in this regard. That’s also why collaborative ventures — like the one that reported and analysed the Panama Papers — represent such a welcome change.

Preview: Trump’s first tweet after the mid-term elections go against Republicans

This from Buzzfeed’s report of the DEFCON conference:

This weekend saw the 26th annual DEFCON gathering. It was the second time the convention had featured a Voting Village, where organizers set up decommissioned election equipment and watch hackers find creative and alarming ways to break in. Last year, conference attendees found new vulnerabilities for all five voting machines and a single e-poll book of registered voters over the course of the weekend, catching the attention of both senators introducing legislation and the general public. This year’s Voting Village was bigger in every way, with equipment ranging from voting machines to tabulators to smart card readers, all currently in use in the US.

So here, just for the record, is a copy of Trump’s first tweet after the results start to come in:

Donald J Trump @realDonaldTrump 3m

FAKE VOTES! Just as we warned, voting machines were HACKED by the Democrats. Results in Michigan and Ohio are FAKE. Shocking, shocking. The mid-terms have been RIGGED. Real Americans won’t accept these fake results.

How the American dream ended

Bleak essay by Frank Rich on the national mood. Sample:

In the Digital Century, unlike the preceding American Century, the largest corporations are not admired as sources of jobs, can-do-ism, and tangible goods that might enrich and empower all. They’re seen instead as impenetrable black boxes where our most intimate personal secrets are bought and sold to further fatten a shadowy Über-class of obscene wealth and privilege trading behind velvet ropes in elite cryptocurrencies. Though only a tiny percentage of Americans are coal miners, many more Americans feel like coal miners in terms of their beleaguered financial status and future prospects. It’s a small imaginative leap to think of yourself as a serf in a society where Facebook owns and markets your face and Alphabet does the same with your language (the alphabet, literally) while paying bogus respects to the dying right to privacy.

It would be easy to blame the national mood all on Donald J. Trump, but that would be underrating its severity and overrating Trump’s role in creating it (as opposed to exacerbating it). Trump’s genius has been to exploit and weaponize the discontent that has been brewing over decades of globalization and technological upheaval. He did so in part by discarding the bedrock axiom of post–World War II American politics that anyone running for president must sparkle with the FDR-patented, chin-jutting optimism that helped propel John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan to the White House. Trump ran instead on the idea that America was, as his lingo would have it, a shithole country in desperate need of being made great again. “Sadly, the American Dream is dead,” he declared, glowering, on that fateful day in 2015 when he came down the Trump Tower escalator to announce his candidacy. He saw a market in merchandising pessimism as patriotism and cornered it. His diagnosis that the system was “rigged” was not wrong, but his ruse of “fixing” it has been to enrich himself, his family, and his coterie of grifters with the full collaboration of his party’s cynical and avaricious Establishment.

Great essay. Worth reading in full.

Global Warning

I’m reading Nick Harkaway’s new novel, Gnomon which, like Dave Eggars’s The Circle, provides a gripping insight into our surveillance-driven future.

Before publication, Harkaway wrote an interesting blog post about why he embarked on the book. Here’s an excerpt from that post:

I remember the days.

I remember the halcyon days of 2014, when I started writing Gnomon and I thought I was going to produce a short book (ha ha ha) in a kind of Umberto Eco-Winterson-Borges mode, maybe with a dash of Bradbury and PKD, and it would be about realities and unreliable narrators and criminal angels in prisons made of time, and bankers and alchemists, and it would also be a warning about the dangers of creeping authoritarianism. (And no, you’re right: creatively speaking I had NO IDEA what I was getting myself into.)

I remember the luxury of saying “we must be precautionary about surveillance laws, about human rights violations, because one day the liberal democracies might start electing monsters and making bad pathways, and we’ll want solid protections from our governments’ over-reach.”

Oops.

I remember the halcyon days of April 2016 when I thought I’d missed the boat and I hadn’t written a warning at all, but a sort of melancholic state of the nation, and I really did think things might get better from there. Then Brexit came – I was half expecting that – and then Trump – which I was really not – and now here we are, with the UK boiling as May’s government and Corbyn’s Labour sit on their hands and clock ticks down and the negotiating table is blank except for a few sheets of crumpled scrap paper, and the only global certainty seems to be that this US administration will try to wreck every decent thing the international community has attempted in my lifetime, with the occasional connivance of our own leaders when they aren’t busy tearing one another to bits.

And now I’m pretty sure I did write a warning after all.

He did.

Does media coverage drive populism? Or is it the other way round?

Very interesting piece of academic research. Title is: “Does Media Coverage Drive Public Support for UKIP or Does Public Support for UKIP Drive Media Coverage?”

Abstract reads:

Previous research suggests media attention may increase support for populist right-wing parties, but extant evidence is mostly limited to proportional representation systems in which such an effect would be most likely. At the same time, in the United Kingdom’s first-past-the-post system, an ongoing political and regulatory debate revolves around whether the media give disproportionate coverage to the populist right-wing UK Independence Party (UKIP). This study uses a mixed-methods research design to investigate the causal dynamics of UKIP support and media coverage as an especially valuable case. Vector autoregression, using monthly, aggregate time-series data from January 2004 to April 2017, provides new evidence consistent with a model in which media coverage drives party support, but not vice versa. The article identifies key periods in which stagnating or declining support for UKIP is followed by increases in media coverage and subsequent increases in public support. The findings show that media coverage may drive public support for right-wing populist parties in a substantively non-trivial fashion that is irreducible to previous levels of public support, even in a national institutional environment least supportive of such an effect. The findings have implications for political debates in the UK and potentially other liberal democracies.

Quote of the Day

” “I stand before you tonight as an uncle, a sports nut, a CEO, a lover of the beautiful Utah outdoors, and a proud, gay American. I come to deliver a simple message that I want every LGBT person to here and to believe.”

“You are a gift to the world,” Cook said. “A unique and special gift, just the way you are. Your life matters. … My heart breaks when I see kids struggling to conform to a society or a family that doesn’t accept them. Struggling to be what someone else thinks is normal. Find your truth, speak your truth, live your truth.”

“Let me tell you,” Cook continued. “‘Normal’ just might be the worst word ever created. We are not all supposed to be the same, feel the same, or think the same. And there is nothing wrong with you.”

“I know that life can be dark and heavy, and sometimes might seem unreasonable and unbearable, but just as night turns to day, know that darkness is always followed by light. You will feel more comfortable in our own skin, attitudes will change. Life will get better and you will thrive.”

Tim Cook at the 2018 Loveloud festival

Thus spake the CEO of the world’s first trillion-dollar company.

Tech companies and ‘fractal irresponsibility’

Nice, insightful essay by Alexis Madrigal. Every new scandal is a fractal representation of the giant services that produce them:

On Tuesday, BuzzFeed published a memo from the outgoing Facebook chief security officer, Alex Stamos, in which he summarizes what the company needs to do to “win back the world’s trust.” And what needs to change is … well, just about everything. Facebook needs to revise “the metrics we measure” and “the goals.” It needs to not ship code more often. It needs to think in new ways “in every process, product, and engineering decision.” It needs to make the user experience more honest and respectful, to collect less data, to keep less data. It needs to “listen to people (including internally) when they tell us a feature is creepy or point out a negative impact we are having in the world.” It needs to deprioritize growth and change its relationship with its investors. And finally, Stamos wrote, “We need to be willing to pick sides when there are clear moral or humanitarian issues.” YouTube (and its parent company, Alphabet), Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, Uber, and every other tech company could probably build a list that contains many of the same critiques and some others.

.People encountering problems online probably don’t think of every single one of these institutional issues when something happens. But they sense that the pattern they are seeing is linked to the fact that these are the most valuable companies in the world, and that they don’t like the world they see through those services or IRL around them. That’s what I mean by fractal irresponsibility: Each problem isn’t just one in a sequence, but part of the same whole.

Interesting also that facebook’s Chief Security Officer has left the company, and that his position is not going to be filled.

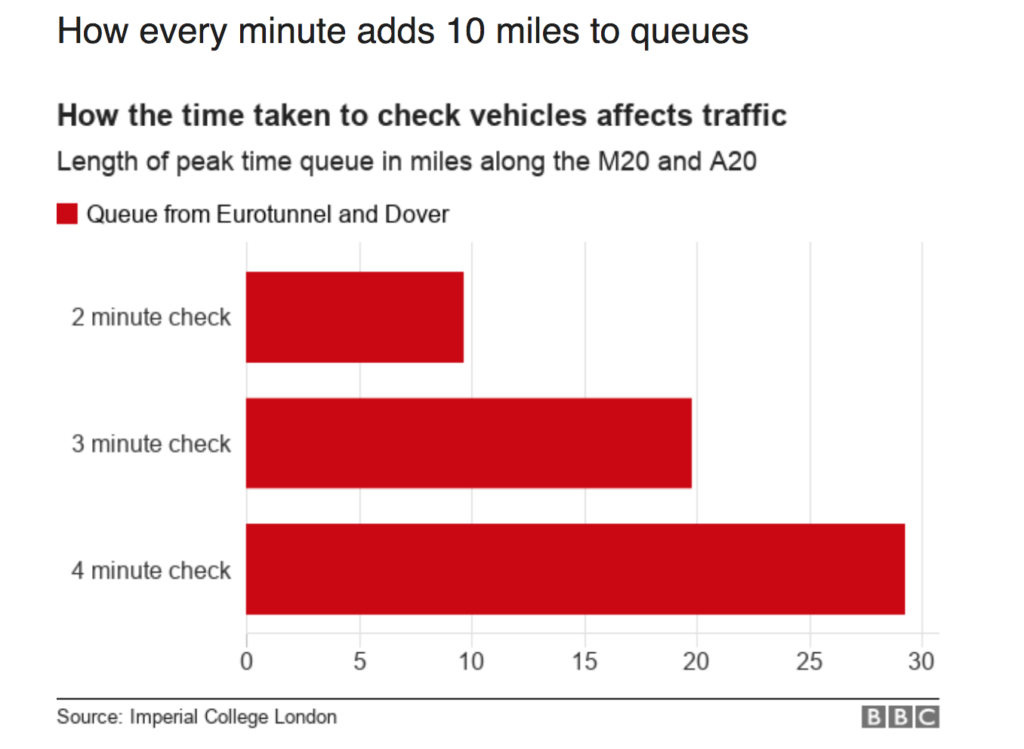

How to turn the M20 into a truck-park

Simple, just opt for the wrong kind of Brexit — one that involves new customs checks at the UK’s borders. Interesting research at Imperial College, London is simulating the likely impact of different assumptions of how long it takes to do the checks at the Channel ports.

The BBC report of the research says:

The research, led by Dr Ke Han, assistant professor in transport, found the current vehicle check time is about two minutes, which can lead to queues of almost 10 miles during peak times, between 16:00 and 19:00.

Queues on the M20 and A20 between Maidstone and Dover would reach 29.3 miles if checks took an average of four minutes, they found.

This would leave drivers waiting almost five hours on the route.

“An extra 10 miles concentrated on local streets resulting from motorway deadlock is entirely possible,” they added.

Figures were compiled using traffic simulations for the area, using data from official sources such as Highways England, the Department for Transport, the Port of Dover and maps.

The research also took into account different kinds of vehicles such as passenger vehicles, light goods vehicles, heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) and coaches.

These simulations look plausible to me. Two years ago, we were coming back from France in August when there were delays at Folkestone because some migrants had got into the tunnel at Calais, which led to the Europe-bound tunnel being closed. We disembarked from the shuttle at about 16:30 and then drove at 70mph for 15 minutes, during which time the France-bound carriageway of the M20 was blocked by three lanes of stationary trucks. That’s a parking lot 17.5 miles long.

The problem with Facebook is Facebook

Kara Swisher has joined the New York Times. Her first column pulls no punches. Sample:

In a post about the latest disinformation campaign, the company said about security challenges: “We face determined, well-funded adversaries who will never give up and are constantly changing tactics. It’s an arms race and we need to constantly improve too.”

The arms race metaphor is a good one, but not for the reasons Facebook intended. Here’s how I see it: Facebook, as well as Twitter and Google’s YouTube, have become the digital arms dealers of the modern age.

All these companies began with a gauzy credo to change the world. But they have done that in ways they did not imagine — by weaponizing pretty much everything that could be weaponized. They have mutated human communication, so that connecting people has too often become about pitting them against one another, and turbocharged that discord to an unprecedented and damaging volume.

They have weaponized social media. They have weaponized the First Amendment. They have weaponized civic discourse. And they have weaponized, most of all, politics.

Lots more where that came from. Worth reading in full.