In today’s Observer there’s a conversation between me and James Gleick, whose book, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood has just been published in the UK.

has just been published in the UK.

Here’s a paradox: we live in an “information age” and yet information is a maddeningly elusive concept. We habitually confuse it with data, on the one hand, and with knowledge on the other. And yet it’s neither. There’s an arcane mathematical discipline called “information theory” that underpins all digital communications nowadays and yet resolutely disdains to make any connection between information and meaning. It would take a brave author to pursue such an elusive quarry. Or a foolhardy one.

James Gleick is an accomplished stalker of mysterious ideas. His first book, Chaos (1987), provided a compelling introduction to a new science of disorder, unpredictability and complex systems. His new book, The Information, is in the same tradition. It’s a learned, discursive, sometimes wayward exploration of a very complicated subject…

I had a nice email this morning from Chris Stewart, a reader in Australia, who had just seen the piece. It reminded him, he said of a limerick that did the rounds in late 1960s Information Science circles. “I have”, he writes, “no idea who wrote it and after quoting it for more than 40 years no one has claimed it …”.

“Shannon and Weaver and I

Have found it instructive to try

To measure sagacity

And channel capacity

With sigma p i log p i”

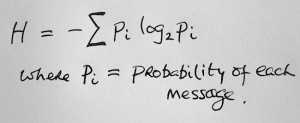

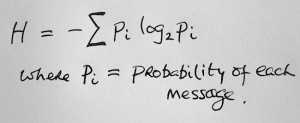

Which is a nice way of summarising Shannon’s formula for information as the measure of ‘unexpectedness’ of a message — H, as here:

“Weaver” refers to Warren Weaver who wrote a piece for Scientific American (“The Mathematics of Communication”, July 1949, p 11-15) explaining the significance of Shannon’s original paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” which had been published in two issues of the Bell Systems Technical Journal in 1948. The book, The Mathematical Theory of Communication by Shannon and Weaver, was published in 1949. It consisted of Shannon’s journal articles plus Weaver’s more accessible explanation.

Maddeningly, I can’t find a copy of Weaver’s SciAm article online, though I’m sure it’s around somewhere. And the SciAm search engine denies all knowledge of Warren Weaver.

Still, apropos the ditty forwarded by Chris Stewart, it’s good to know that Limerick, Ireland’s fourth city, is located on the Shannon, which is Ireland’s largest river.