George Steiner: an appreciation

I knew and liked George Steiner, who died on Monday last at the age of 90. The *Observer asked me to wrote an appreciation of him. Here’s a sample:

I first met George in the 1980s, when I was a TV critic. At the time, Channel 4 was running a high-IQ chatshow called Voices, in which the host, the poet and critic Al Alvarez, batted around ideas with a panel of prominent public intellectuals. One evening, I watched, mesmerised, as George fluently extemporised for 10 whole minutes – without notes, hesitation or much repetition – on the question of whether an authoritarian political system can produce more artistic creativity than the “free” west.

My review included a riff on a literary phenomenon – the Steiner sentence – a formidable expressive work that came, perfectly formed, with an ancillary apparatus of footnotes, subordinate clauses and scholarly asides, and went on long after the programme had come to an end, the lights had been switched off and the entire production crew had gone home to bed. And having dispatched the review, I too switched off and went to bed.

A few days later, a postcard arrived from George inviting me to lunch at the Green Man in Grantchester, where we had an enjoyable, convivial conversation…

Do read the whole thing

Democrats should have seen their Iowa tech meltdown coming

Today’s Observer column:

Who needs the Russians when the Democratic party of Iowa is perfectly capable of screwing up the democratic process all by itself? The political world waited on Monday night with bated breath to see which of the Democratic candidates would emerge from the arcane “caucus” process in the state. But when the polls closed, no results were available.

There were, the party, stated, “inconsistencies” in the reported figures coming through from the precincts. No results would be issued until the results had been properly and accurately collated. The information was to have come from a recently developed smartphone app, with a back-up option that would enable precinct captains to phone in their results. Neither channel worked. CNN reported that one official who was trying to report his results was on hold for an hour and had apparently just got through to party headquarters when the party hung up on him – on live television. It was, to use a technical term, a shambles…

Events, dear Mr Xi, events

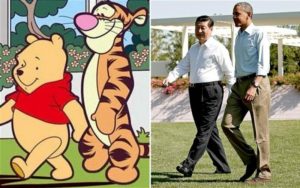

Harold Macmillan’s timeless reply to the journalist who asked him what kept him awake at night (“Events, dear boy, events.”), keeps coming to mind. I’m wondering now if the Corona virus, and in particular popular anger at the harassment and death of Li Wenliang — the young doctor who first raised the possibility that a new virus was loose might — in the end, lead to the downfall of the current Great Leader, Winnie the Pooh, as he is satirically known.

In that context, there’s an interesting piece in today’s Observer:

“The fallout from the spread of the potentially deadly coronavirus is already grim”, writes Richard McGregor,

most immediately in the form of a reeling Chinese economy that is having to temporarily sever supply lines to factories and retail outlets around the world. China has been responsible for about one-third of global growth in recent years, a greater share than the US, and any slowdown in its economy will be felt across the world.

But the greatest focus is on what Li alluded to when he complained about the country being ruled by “one voice”, which Chinese people would immediately recognise as a barb directed at Xi Jinping. Xi has swept all enemies, real and imagined, aside since taking over as Communist party chief in late 2012 and made many more along the way.

Powerful families and moneyed interests toppled by his relentless anti-corruption campaign will never forgive him and are lying in wait for revenge. Equally, many of the technocratic elite have been alienated by his illiberal economic policies and his assertiveness overseas, which they blame for triggering a concerted pushback in Washington.

Much of their anger was captured in a single moment that embodied their fears that Xi is taking the country backwards – his decision in early 2018 to do away with term limits and make himself leader in perpetuity.

I was talking to a China expert last night who believes that the thing that terrifies local Chinese Communist party bosses is that the people will one day become really pissed off with them.

Eventually Xi will discover that nothing lasts forever. In the end the real Winnie the Pooh’s grip on the popular imagination will outlast him.