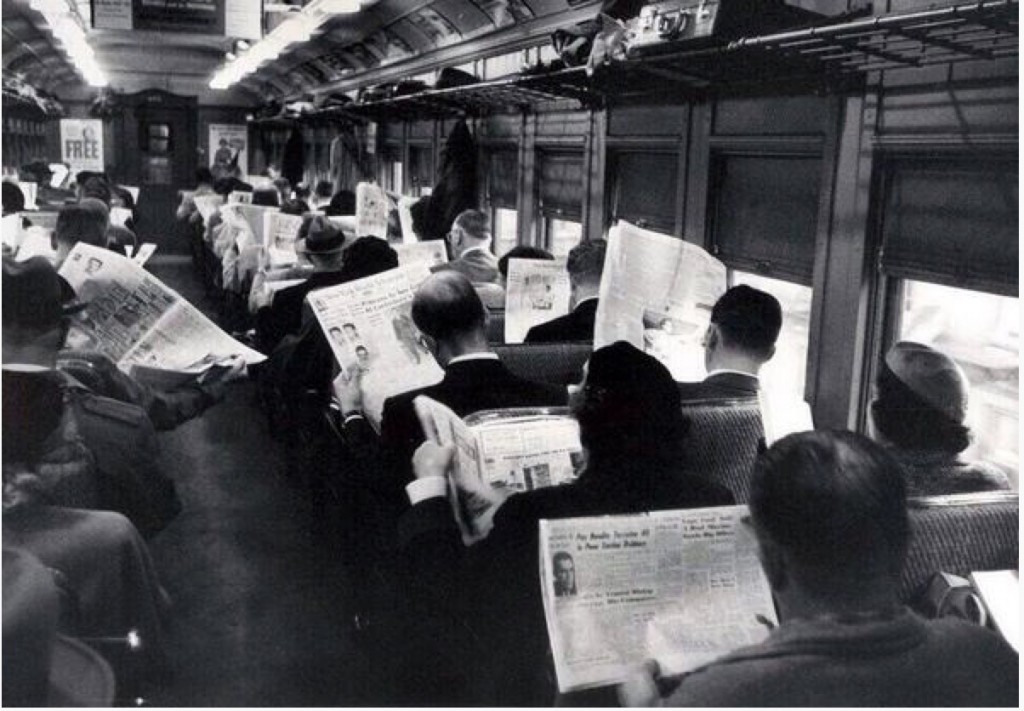

Nice pic, which makes a good point for those who complain about everyone looking at phones on contemporary trains). Provenance unknown. (via @webtechman on Twitter)

Category Archives: Media ecology

Taking global warming to heart

For a first-time movie, this is quite something. It comes from a fascinating account of a session at NYU Journalism School on stills photographers using video to tell stories where stills don’t quite do the trick.

How the network is evolving

This morning’s Observer column:

Earlier this year engineer Dr Craig Labovitz testified before the US House of Representatives judiciary subcommittee on regulatory reform, commercial and antitrust law. Labovitz is co-founder and chief executive of Deepfield, an outfit that sells software to enable companies to compile detailed analytics on traffic within their computer networks. The hearing was on the proposed merger of Comcast and Time Warner Cable and the impact it was likely to have on competition in the video and broadband market. In the landscape of dysfunctional, viciously partisan US politics, this hearing was the equivalent of rustling in the undergrowth, and yet in the course of his testimony Labovitz said something that laid bare the new realities of our networked world…

More…

Wired had an interesting series about this shift, the first episode of which has a useful graphic illustrating the difference between most people’s mental model of the Internet, and the emerging reality.

Big Ben

David Remnick has a lovely memoir of Ben Bradlee in the New Yorker which captures the essence of the man (and mentions the one black spot on his record, namely the way his friendship with JFK blurred his journalistic judgement). Remnick is a delightful writer with a good ear for anecdote. Take this, for example:

During his reign, from 1968 to 1991, as the executive editor of the Washington Post, Bradlee took time periodically to dictate correspondence into a recorder. His letters in no way resembled those of Emily Dickinson. He was given neither to self-doubt nor to self-restraint. In his era, there may have been demands by isolated readers for greater transparency, for correction or explanation, but there was no Internet, no Twitter, to amplify them. Bradlee was, by today’s standards, unchallengeable, and he was expert in the art of florid dismissal. His secretary, Debbie Regan, was, in turn, careful to reflect precisely his language when transcribing his dictation. One day, Regan approached the house grammarian, an editor named Tom Lippman, and admitted that she was perplexed. “Look, I have to ask you something,” she said. “Is ‘dickhead’ one word or two?”

In the film about the Watergate saga, All the President’s Men, Bradlee was played by Jason Robard, and many people — including me — thought that he had probably hammed it up a bit. Remnick disagrees:

Younger people watching the actor Jason Robards’s portrayal of Bradlee in “All the President’s Men” can be forgiven for thinking it is a broad caricature, an exaggeration of his cement-mixer voice, his cocky ebullience, his ferocious instinct for a political story, and his astonishing support for his reporters. In fact, Robards underplayed Bradlee. Recently, Tom Zito, a feature writer and critic at the Post during the Bradlee era, told me this story:

“One afternoon in the fall of 1971, I was summoned to Ben’s office. I was the paper’s rock critic at the time. A few minutes earlier, at the Post’s main entrance, a marshal from the Department of Justice had arrived, bearing a grand-jury subpoena in my name. As was the case ever since the Department of Justice and the Post had clashed over the Pentagon Papers, earlier that year, rules about process service dictated that the guard at the front desk call Bradlee’s office, where I was now sitting and being grilled about the business of the grand jury and its potential impact on the paper. I explained that my father was of Italian descent, lived in New Jersey, had constructed many publicly financed apartment buildings—and was now being investigated by the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York regarding income-tax evasion. ‘Your father?’ Ben exclaimed in disbelief, and then called out to his secretary, ‘Get John Mitchell on the phone.’ In less than a minute, the voice of the Attorney General could be heard on the speaker box, asking, somewhat curtly, ‘What do you want, Ben?’ In his wonderfully gruff but patrician demeanor, and flashing a broad smile to me, Ben replied, ‘What I want is for you to never again send a subpoena over here asking any of my reporters to give grand-jury testimony about their parents. And if you do, I’m going to personally come over there and shove it up your ass.’ The subpoena was quashed the next day.”

Remnick also quashes the notion that Bradlee was an ideological creature: he wasn’t. What he was, though, was a fierce believer in the First Amendment.

I’m sending the link to Remnick’s essay to my students on our Masters in Public Policy course because we had been talking in class about the decline of the print-journalism era. I was about to append a postcript in Irish — Ní bheidh a leithéad arís ann (We shall not see his like again) — but thought better of it. After all, the Snowden saga suggests that the Bradlee spirit is still alive and well, at least in some corners of our media jungle.

Celebrating Dave Winer

This morning’s Observer column:

Twenty years ago this week, a software developer in California ushered in a new era in how we communicate. His name is Dave Winer and on 7 October 1994 he published his first blog post. He called it Davenet then, and he’s been writing it most days since then. In the process, he has become one of the internet’s elders, as eminent in his way as Vint Cerf, Dave Clark, Doc Searls, Lawrence Lessig, Dave Weinberger or even Tim Berners-Lee.

When you read his blog, Scripting News – as I have been doing for 20 years – you’ll understand why, because he’s such a rare combination of talents and virtues. He’s technically a very gifted software developer, for example. Many years ago he wrote one of the smartest programs that ever ran on the Apple II, the IBM PC and the first Apple Mac – an outliner called ThinkTank, which changed the way many of us thought about the process of writing. After that, Winer wrote the first proper blogging software, invented podcasting and was one of the developers of RSS, the automated syndication system that constitutes the hidden wiring of the blogosphere. And he’s still innovating, still pushing the envelope, still writing great software.

Technical virtuosity is not what makes Winer one of the world’s great bloggers, however. Equally important is that he is a clear thinker and writer, someone who is politically engaged, holds strong opinions and believes in engaging in discussion with those who disagree with him. And yet the strange thing is that this opinionated, smart guy is also sensitive: he gets hurt when people write disparagingly about him, but he also expresses that hurt in a philosophical way…

Celebgate: what it tells us about us

My Observer Comment piece on the stolen selfies.

Ever since 1993, when Mosaic, the first graphical browser, transformed the web into a mainstream medium, the internet has provided a window on aspects of human behaviour that are, at the very least, puzzling and troubling.

In the mid-1990s, for example, there was a huge moral panic about online pornography, which led to the 1996 Communications Decency Act in the US, a statute that was eventually deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. But when I dared to point out at the time in my book (A Brief History of the Future: The Origins of the Internet), that if there was a lot of pornography on the net (and there was) then surely that told us something important about human nature rather than about technology per se, this message went down like a lead balloon.

It still does, but it’s still the important question. There is abundant evidence that large numbers of people behave appallingly when they are online. The degree of verbal aggression and incivility in much online discourse is shocking. It’s also misogynistic to an extraordinary degree, as any woman who has a prominent profile in cyberspace will tell you…

Why Facebook is for ice buckets and Twitter is for what’s actually going on

Tomorrow’s Observer column

Ferguson is a predominantly black town, but its police force is predominantly white. Shortly after the killing, bystanders were recording eyewitness interviews and protests on smartphones and linking to the resulting footage from their Twitter accounts. News of the killing spread like wildfire across the US, leading to days of street confrontations between protesters and police and the imposition of something very like martial law. The US attorney general eventually turned up and the FBI opened a civil rights investigation. For days, if you were a Twitter user, Ferguson dominated your tweetstream, to the point where one of my acquaintances, returning from a holiday off the grid, initially inferred from the trending hashtag “#ferguson” that Sir Alex had died.

There’s no doubt that Twitter played a key role in elevating a local killing into national and international news. (Even Putin’s staff had some fun with it, offering to send human rights observers.) More than 3.6m Ferguson-related tweets were sent between 9 August, the day Brown was killed, and 17 August.

Three cheers for social media, then?

Not quite. ..

Recycled news

Lovely column by Jack Shafer about why news headlines seem so familiar. Sample:

But the periodicity of the news has another cause, as press scholar Jack Lule discovered more than a decade ago in his book Daily News, Eternal Stories. Lule proposed that the news was less a pure journalistic creation than it was the modern expression of ancient myths.

Like many all-encompassing formulas, Lule’s reduction of news into myth suffers by attempting to explain too much. But after reading his book, you can’t help but notice how many front-page stories collapse into the seven master myths he assembles (which will sound familiar to anybody who has brushed up against Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces): the victim, a casualty of randomness or a villain; the scapegoat, who is punished for straying outside the social order; the hero, who smites evil; the good mother, who “offers maternal comfort and protection”; the trickster, the rogue who disturbs the social order; the other world, typically foreign countries; and the flood, or any other disaster.

Lovely stuff. Worth reading in full.

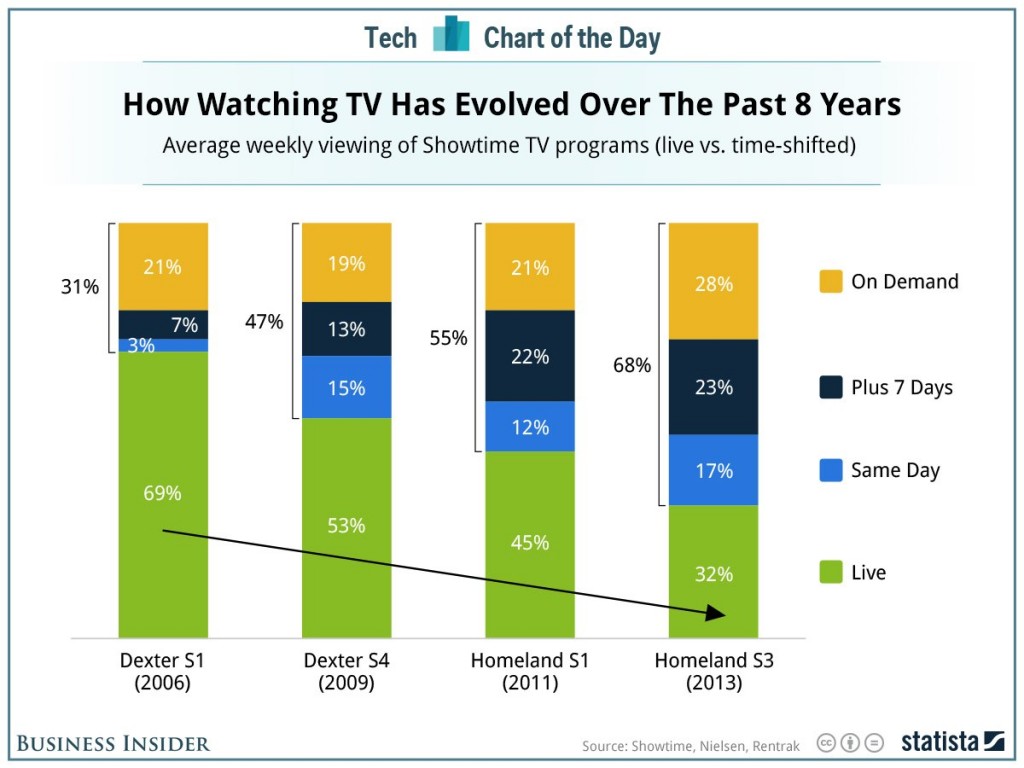

The slow death of water-cooler TV

Why Wikipedia matters

This morning’s Observer column.

Wikipedia is a typical product of the open internet, in that it started with a few simple principles and evolved a fascinating governance structure to deal with problems as they arose. It recognised early on that there would be legitimate disagreements about some subjects and that eventually corporations and other powerful entities would try to subvert or corrupt it.

As these challenges arose, Wikipedia’s editors and volunteers developed procedures, norms and rules for addressing them. These included software for detecting and remedying vandalism, for example, and processes such as the “three-revert” rule. This says that an editor should not undo someone else’s edits to a page more than three times in one day, after which disagreements are put to formal or informal mediation or a warning is placed on the page alerting readers that there is controversy about the topic. Some perennially disputed pages, for example the one on George W Bush, are locked down. And so on.

In trying to figure out how to run itself, Wikipedia has therefore been grappling with the problems that will increasingly bug us in the future. In a comprehensively networked world, opinions and information will be super-abundant, the authority of older, print-based quality control and verification systems will be eroded and information resources will be intrinsically malleable. In such a cacophonous world, how will we know what is reliable and true? How will we deal with disagreements and disputes about knowledge? How will we sort out digital wheat from digital chaff? Wikipedia may be imperfect (what isn’t?) but at the moment it’s the only model we have for addressing these problems.