Does it make sense to confine Huawei to the ‘non-core’ part of a 5G network?

This seems to be the UK’s fallback position to avoid antagonising the Chinese state (though it won’t mollify the Americans). Bruce Schneier has some interesting things to say about this. Sample:

The 5G security problems are threefold. First, the standards are simply too complex to implement securely. This is true for all software, but the 5G protocols offer particular difficulties. Because of how it is designed, the system blurs the wireless portion of the network connecting phones with base stations and the core portion that routes data around the world. Additionally, much of the network is virtualized, meaning that it will rely on software running on dynamically configurable hardware. This design dramatically increases the points vulnerable to attack, as does the expected massive increase in both things connected to the network and the data flying about it.

Second, there’s so much backward compatibility built into the 5G network that older vulnerabilities remain. 5G is an evolution of the decade-old 4G network, and most networks will mix generations. Without the ability to do a clean break from 4G to 5G, it will simply be impossible to improve security in some areas. Attackers may be able to force 5G systems to use more vulnerable 4G protocols, for example, and 5G networks will inherit many existing problems.

Third, the 5G standards committees missed many opportunities to improve security. Many of the new security features in 5G are optional, and network operators can choose not to implement them. The same happened with 4G; operators even ignored security features defined as mandatory in the standard because implementing them was expensive. But even worse, for 5G, development, performance, cost, and time to market were all prioritized over security, which was treated as an afterthought.

Schneier’s view is that “It’s really too late to secure 5G networks”. 5G security, he says,

is just one of the many areas in which near-term corporate profits prevailed against broader social good. In a capitalist free market economy, the only solution is to regulate companies, and the United States has not shown any serious appetite for that.

What’s more, U.S. intelligence agencies like the NSA rely on inadvertent insecurities for their worldwide data collection efforts, and law enforcement agencies like the FBI have even tried to introduce new ones to make their own data collection efforts easier. Again, near-term self-interest has so far triumphed over society’s long-term best interests.

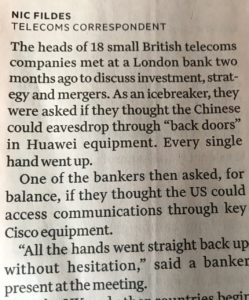

And of course there’s also the fact that there have probably always been US-friendly backdoors in Cisco kit, as this report from the FT the other day suggests.

Sajit Javid and the ‘quiet hegemon‘ he’s clearly never heard about

Javid, who is currently Chancellor of the Exchequer, was grandstanding the other week about how the liberated UK would break free of EU red tape. In an interview with the Financial Times he warned UK manufacturers that “there will not be alignment” with the EU after Brexit and insisted that firms must “adjust” to new regulations.

Not surprisingly, this caused alarm in many business sectors whose prosperity depends on adhering to EU regulations. And so Javid — possibly under instruction from Number 10 — started to row back, saying that the government will only use the freedom to diverge if it thinks the change is worthwhile, and after the pros and cons have weighed up.

The Chancellor has form in shooting his mouth off. I remember that he spoke at the launch of the previous government’s White Paper on online harms. He was then Home Secretary (aka Minister of the Interior) and his speech was less about online harms and more about how he was the tough guy who would stamp out this kind of harm. In effect, it was part of his campaign to replace Theresa May, then on her last legs as Premier.

I viewed his Financial Times interview through the same lens. He’s like Boris Johnson during May’s tenure, perpetually in campaigning mode. There are however, some harsh realities about regulatory divergence that suggest he could be riding for a fall. Today, for example, the CEO of Volvo is reported (by the FT) as saying that certifying his company’s cars for the UK market would not be worth the cost if UK rules diverged significantly from the EU’s. The result, UK consumers would have a smaller range of Volvos to choose from. And there’s an interesting new book out — The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World by Ann Bradford, an academic study detailing how, in a world increasingly driven by standards, EU standards have quietly become global standards. (Think GDPR.)

In that way, the EU has become a “quiet hegemon” of which it seems the Westminster bubble is blissfully unaware.