Category Archives: Capitalism

Technology and the future of work

Our Technology and Democracy research project had a terrific talk this afternoon by Mike Osborne of the Oxford Martin School about the research that he and Carl Frey published in “The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation?”.

That paper is impressive in lots of ways. Unlike many academic research reports, for example, it’s written in pellucid prose. And it’s historically informed — which is unusual in technology publications: the authors know that the issue of the impact of machinery on jobs goes back a long, long way — at least to Elizabethan times with William Lee and his request for a patent on his stocking frame loom.

But most importantly, the Frey-Osborne study is the best analysis to date of what we in our project regard as one of the most significant puzzles of our time: namely what does the combination of infinite computational power, big data, machine learning and advanced robotics mean for our future? Or, to quote the title of Norbert Wiener’s book, what will constitute “the human use of human beings” in a digital future?

What preoccupies us is the question of whether we now stand on a hinge of history. Are there things about digital technologies which make our situation and prospects different from the disruptions that our ancestors faced when confronted with the seminal general-purpose technologies of the past? Can we say with any confidence that this time it’s different?

Mike’s presentation provoked lots of thoughts…

The first is the objection often made by historians and economists who argue say that apocalyptic concerns about digital technology are just outbreaks of a-historical hysteria. Historically, they say, technological progress has always had two conflicting impacts on employment. One is the overtly destructive impact — the leading edge of the Schumpeterian wave, if you like. The other is the capitalisation effect, as companies start to enter industries where productivity is relatively high, leading to the expansion of employment in these new or revitalised industries. So, according to the sceptics, although automation definitely taketh away, it also giveth.

But if I’ve understood Mike and Carl’s work correctly, this time it might be different, for two reasons.

-

One is that whereas automation historically served to eliminate manual and/or highly routinised tasks, the new digital technologies mean that automation is remorselessly moving into work domains that have traditionally been seen as cognitive and non-routine.

-

The second is that what happening now is what Brian Arthur called “combinatorial innovation”, which is basically the network effect applied to technological innovation. This means that the pace of innovation is increasing exponentially, which in turn means that our traditional capacity to transition into employment in new areas is going to be outpaced by the pace of change. In which case, the life-chances of a lot of human beings could be undermined or destroyed.

Which leads to a final thought, namely that in the end this will have to come down to politics. Mike and Carl’s analysis is not a deterministic one — they don’t imply that the job-destruction that they think could happen will happen. Decisions about whether to deploy these technologies will, in the end, be made by people –- the owners of capital — not by machines. And if there’s no element of societal control in all this, then the clear implication is that Piketty’s rule about the returns from capital generally outrunning the returns from employment will be turbocharged, with predictable consequences for inequality.

But of course, it doesn’t have to be like that. The economic and productivity gains that result from these technologies could be used for different purposes other than giving even more to those who already have. And that brings to mind Keynes’s famous essay on “The Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” in which he saw the possibility that, through technology-driven productivity gains, man “could for the first time since his creation … be faced with his real, his permanent problem — how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well”.

Only politics can ensure that that agreeable prospect comes to pass, however. This isn’t just about technology, in other words.

And now here’s the really strange thing: in all the sturm und drang of our recent election campaign, the implications of computerisation for employment weren’t mentioned once. Not once.

Our fragile, incomprehensible networked world

This morning’s Observer column:

At first sight, it looked like an April Fools’ story. The US Department of Justice is seeking to extradite a day-trader from Hounslow to stand trial on charges that he brought the US stock market briefly to its knees on 6 May 2010. Navinder Singh Sarao is accused of using a computerised share-trading program to manipulate the market for S&P 500 futures contracts on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, thereby adding (so the prosecution alleges) to wider selling pressure that caused the Dow Jones industrial average to plunge briefly by 6% before bouncing back.

In that short interval, stocks in huge companies such as Procter & Gamble dropped by 25% and established companies such as General Electric and Accenture briefly traded as penny shares. The British courts, not to mention the rest of us, are invited to believe that this mayhem was caused by a 36-year-old geek in the bedroom of his parents neat semi-detached house under the Heathrow flight path.

There are, it seems to me, only two possible interpretations of this. One is that Mr Sarao is indeed responsible for the chaos. The other is that the US authorities have no real idea who is responsible, but need to make an example of somebody and Mr Sarao will do nicely. Either way, we are left with a really alarming conclusion, namely that we have constructed a world that is totally dependent on systems that are a) astonishingly fragile and unpredictable, and b) incomprehensible not only to the average citizen but to those who are supposed to regulate them…

The economics of Wolf Hall

As I’ve observed, Peter Kosminski’s wonderful adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s novels has lots of contemporary resonances. In today’s Guardian the paper’s Economics Editor, Larry Elliott, picks up on some of the points the series makes about economics and social mobility. Sample:

What the small screen adaptation can’t really capture from Wolf Hall and the follow-up volume, Bring Up The Bodies, is the book’s broader themes. Mantel’s Cromwell tells us a lot about power and intrigue at the Tudor court. But he also tells us about class, the rise of capitalism and an economy in flux.

The period of transition from feudalism to modern capitalism was long. Economic growth in the 16th century barely kept pace with the growing population. The economy had its ups and down but broadly flatlined between 1500 and 1600. More than two centuries would pass before the advent of the wave of technological progress associated with the start of the industrial revolution.

Even so, the economy was gradually being transformed. Cromwell was not a member of the old aristocratic families: a Suffolk or a Norfolk. He was a blacksmith’s son from Putney made good. Like his patron, Cardinal Wolsey, he did not have a privileged upbringing but had talent and ambition. Karl Marx would have seen Cromwell as a classic example of the new bourgeoisie. Mantel draws a contrast between the fanatically devout Thomas More and the worldly wise Cromwell: the one settling in for a day’s scourging, the other off to get the day’s exchange rate in the City’s Lombard Street, where all the big banking houses had their home.

The inference is clear. Men like More are the past. A new breed of men, pragmatic and servants of the state not the church, are on the rise. “He can converse with you about the Caesars or get you Venetian glassware at a very reasonable rate. Nobody can better keep their head, when markets are falling and weeping men are standing on the street tearing up letters of credit.”

AdvertisementThis, of course, is fiction not fact. But the challenge to the status quo from men like Cromwell was real enough…

A key factor in the story, of course, is the fact that Cromwell was an early Protestant. Elliott goes on to draw on the work of David Landes who argued in The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, that the challenge to the Vatican from the new religion was a major influence because it signified the dawning of a more secular age.

Once he had made Henry supreme over the Church of England and disposed of Anne Boleyn, he set to work on the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Rather like the privatisation programme of the 1980s, the main reason for the assault on the monasteries was financial: Henry was short of money and wanted the funds to fight his expensive wars. Cromwell could justify what was effectively the enforced nationalisation of church lands by pointing to the corruption of the monastic ideal, but this was of secondary importance.

Nothing really changes. Governments always seem to be short of money. A modern Cromwell charged with sorting out the public finances might conclude that the financial sector – rich, arrogant and with a lamentable record of corruption – was ripe for the picking. No question: if Cromwell was alive today, the former chief executive of HSBC, Stephen Green, would be in chains in the Tower and the Dissolution of the Banks would be in full swing.

Great stuff.

Marissa Mayer and Yahoo’s USP-deficit

My Observer review of Nicholas Carlson’s Marissa Mayer and the Fight to Save Yahoo.

[Yahoo] grew rapidly in the late 1990s, riding the crest of the first internet boom and metamorphosing into a “portal” – a gateway to the web. By 1999, Yahoo had 4,000 employees, 250 million users and $590m in annual revenues – much of it from advertising by dotcom firms. In March 2000 its market cap peaked at $128bn.

And then came the crash. The dot-com bubble burst, the laws of economic gravity reasserted themselves and ever since then Yahoo has been struggling to find its raison d’etre. The question that has always bedevilled it is the classic one from children’s books: Mummy, what is that company for? For its competitors, the answer is generally straightforward: Google is for search; Facebook is for social networking; Amazon is for online retail, and possibly world domination; Microsoft is for Office and desktop computers. But nobody really knows what Yahoo is for – what its unique selling proposition is.

This USP-deficit is largely a product of the company’s history. Its co-founders are genial hippie types who weren’t even sure they wanted to found a company…

The concierge economy

My Observer essay on the implications of Uber:

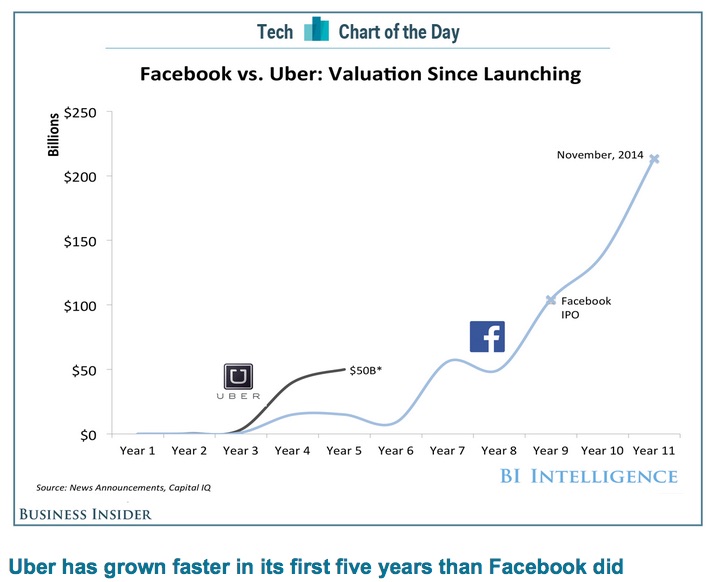

In a way, the name of the company – Uber – gives the game away. It has connotations of elevation, superiority, authority – as in Nietzsche’s coinage, Übermensch, to describe the higher state to which men might aspire. Although it’s only been around since 2009, Uber, the smartphone-enabled minicab company, is probably the only startup of recent times to have achieved the same level of name recognition as the established internet giants.

This is partly because Uber is arguably the most aggressive tech startup in recent history and partly because it has attracted a lot of bad press. But mainly it’s because a colossal pile of American venture capital is riding on it. Its most recent investment round valued the company at about $40bn, which is why every MBA graduate in California is currently clutching a PowerPoint presentation arguing that his/her daft idea is “Uber for X” – where X is any industry you care to mention.

What lies behind the frenzy is a conviction that Uber is the Next Big Thing, fuelled by the belief that it is the embodiment of what Silicon Valley values most, namely “disruptive innovation” – as in disruption of established, old-economy ways of doing things…

LATER

Om Malik has a very thoughtful essay which starts with a meditation on a conversation he had with an Uber driver, and then moves into a meditation on the apps economy.

Keith [Malik’s Uber driver], who aspires to be in the fashion business was pretty ruthless in his assessment of the company and brought up many questions that have coursed through my mind. He appreciates the financial flexibility Uber has provided him — his luxury car rental business wasn’t enough and he has benefitted from this augmented income. He isn’t the first one who felt that Uber look some pressure off their back — the other day I met a $12-an-hour bouncer at a Tenderloin music venue who is happy dealing with traffic rather than drunks and strung out addicts. “It was worth $19 billion three months ago and now it is worth $41 billion,” says Keith, “isn’t that something. And yet they don’t care about their contractors.”

Still, like many others Keith is befuddled by Uber’s treatment of its contractors. Many of the rule changes seem arbitrary and he too is confused by the tone-deafness of the company. He laments the recent directive (later modified) by Uber to classify all cars before 2010 as a UberX and thus relegated them to lower money making tier. When I point out that as a customer if I am paying premium prices, why shouldn’t I get a premium experience. Today, you end up riding in “black cars” who are a pale imitation of their real self. Shouldn’t the car upgrades result in better cars and through process of elimination bring fewer, but better drivers on the road? Like most drivers, Keith agrees, but points out that logic and reality of being a contract driver are two different things.

It is very hard for people to understand that it isn’t easy to upgrade your car, especially when you are trying to make a living driving an Uber in an intensely competitive marketplace where there are more cars on the road and the pie is getting sliced into thinner and thinner slices. Still, Keith said that he was planning to upgrade, though he didn’t care much for Uber’s financial plans or deals with car companies — he is going to get a Mercedes as part of the upgrade. During our conversation, Keith points out that Uber is good for helping him and others make money in the near term, but the current model doesn’t allow much optimism for the future, thanks to too many cars, too many rules and demand which isn’t rising as fast as the cars.

LATER STILL: this:

Dan Sperling, Founding Director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis, says that while Uber “will continue to do battle with local and state authorities, it’s pretty clear that they’ve got a very good business model, they’ve got a lot of momentum, and they’ve got a very good product that people love. They’ll figure out a way around the challenges because it’s clear they provide a valuable service. And that’ll force regulators to reassess their rules, some of which were written up years ago and make absolutely no sense today.’’

As Sperling sees it, “while it’s true that taxis are way over-regulated, the answer is not to smother all the babies competing with them; the answer is to regulate the Ubers of the world better while you deregulate the taxi industry.’’

And what about that $40 billion price tag? Uber and its rivals “are entering a marketplace that has seen almost no innovation in many decades,’’ according to Sperling, who says adding courier and food-delivery services could make Uber even more of a behemoth. “There’s a lot of pent-up demand for real-time, on-demand-type services, so there’s huge upside potential here.’’

Cowardice, Hollywood style

George Clooney nails it in an interview with Deadline.

DEADLINE: How could this have happened, that terrorists achieved their aim of cancelling a major studio film? We watched it unfold, but how many people realized that Sony legitimately was under attack?

GEORGE CLOONEY: A good portion of the press abdicated its real duty. They played the fiddle while Rome burned. There was a real story going on. With just a little bit of work, you could have found out that it wasn’t just probably North Korea; it was North Korea. The Guardians of Peace is a phrase that Nixon used when he visited China. When asked why he was helping South Korea, he said it was because we are the Guardians of Peace. Here, we’re talking about an actual country deciding what content we’re going to have. This affects not just movies, this affects every part of business that we have. That’s the truth. What happens if a newsroom decides to go with a story, and a country or an individual or corporation decides they don’t like it? Forget the hacking part of it. You have someone threaten to blow up buildings, and all of a sudden everybody has to bow down. Sony didn’t pull the movie because they were scared; they pulled the movie because all the theaters said they were not going to run it. And they said they were not going to run it because they talked to their lawyers and those lawyers said if somebody dies in one of these, then you’re going to be responsible.

This is interesting because it suggests a promising new line for real and would-be ‘terrorists’: simply issue vague threats about nameless horrors to be visited upon public venues in the US and corporate lawyers will do the rest.

The hegemony of marketisation

Technically hegemony is “is the political, economic, or military predominance or control of one state over others” and in the world of realpolitik (e.g. Ukraine at the moment; or the cringe-making UK-US ‘special relationship’) it’s a grim reality. But it’s also a phenomenon in intellectual life, where it signifies that a particular ideology has become so pervasive and dominant that it renders alternative viewpoints/ideologies literally unthinkable. Since the 1970s, neoliberalism (aka “capitalism with the gloves off”) has increasingly acquired that hegemonic status, to the point where it now infects every aspect of public policy.

I came up against this yesterday when I had a conversation with someone who described the BBC as an “intervention in media markets”. I balked at this: the BBC, it seems to me, is a public service which existed long before there were media markets of any recognisable kind, and it was therefore not designed to be an “intervention” in anything other than the public sphere. And even now, when there are global media markets with which the BBC co-exists, it’s misleading — even for those who approve of the BBC and public service broadcasting services generally — to view it as an “intervention” to remedy market ‘failure’. The fact that the commercial media market doesn’t provide publicly-valuable services isn’t a ‘failure’ of that market. Commercial markets exist to make profits, and media markets are doing just fine at that. Any societal benefits they happen to provide — unbiased current affairs coverage, employment — are side effects of the core business.

But after the conversation I fell to brooding on the dominance of market ideology in the thinking of the policy-makers I meet — which is where the idea of hegemony came from. Since the 1970s we have all become like one-club golfers: whenever a policy issue arises we tend to think about it in terms of markets. We’ve seen that in the National Health Service in the UK; and in the 1980s and 1990s we saw it in the way the Birt regime that ran the BBC conceptualised the corporation’s alleged inefficiencies in terms of the absence of an “internal market”, which it then implemented under the banner of “Producer Choice”. (Which in turn led to celebrated absurdities, like the “£100 black tie” — of which more later.)

The truth is that markets are good at some things and hopeless at others. If you think about them in functional terms, they are self-organising systems which operate by transmitting price signals to their participants. These signals tell participants whether their strategy/tactics are working or not, and indicate the direction of change needed to rectify things. But when policy-makers reach for marketised solutions to operational or administrative malfunction in non-market institutions they have to distort the institution so that they ape market affordances. And since the only signals that markets send are prices, marketised non-market institutions have to invent pseudo-prices in order to function. Which often leads to absurd outcomes, and usually means that organisations that need to harness the synergies that come from departments working together become less than the sum of their parts, because the parts are now ‘trading’ with or against one another.

Just to take the BBC as an example. Pre-Birt, the BBC had a fabulous research library which was available — free — to every employee of the corporation. Similarly, it had a wonderful Wardrobe department, also available free to every producer. After the introduction of ‘producer choice’, these services were no longer free, so producers and researchers had to make a decision about whether the budget could afford a lot of library research, or whether to experiment with a range of costumes. As told to me by a BBC insider, the legendary £100 black tie episode arose as follows. The News and Current Affairs department used to periodically rehearse plans for covering the death of the then Queen Mother. To be realistic, these rehearsals had obviously to be unannounced in advance: staff would have to drop what they were doing and go into Queen-Mother-dead routine. This required the (all-male) News anchors to wear black ties. On one such occasion, none of them had a black tie, so a request was sent to Wardrobe. Wardrobe quoted an internal price that the producer regarded as exorbitant. So a production assistant was dispatched to M&S in a taxi in order to procure said ties. The cost, including taxi fares, came to £100 per tie.

I’ve no idea if this story is true or not. It does, however, illustrate something that I believe to be true, namely that phoney internal markets are an absurdly inefficient way of organising the feedback signals needed to make departments responsive to failure or inefficient performance. But a signalling system is essential to avoid the kind of stasis, complacency and conservatism that often characterises non-market institutions. The good news is that with computing and networking technology we now have lots of ways of signalling satisfaction/dissatisfaction — e.g. by means of online and instantaneous rating systems. They’re not magic bullets (witness the ways in which customer ratings of Uber drivers can be dysfunctional), but compared with the absurdities implicit in distorting non-market institutions to make them mimic markets, they’re likely to be much less damaging.

“Ruthless execution and total arrogance”

Which just about sums up the Silicon Valley ideology. And, as Sara Haider points out,

Emil Michael can say stupid things at a dinner, and garner exceptional attention because Uber is a $30 billion company in the brightest spotlight. And they’ll be there for a while longer. But the Uber attitude and behavior permeates our entire industry: an industry of new money, enormous power…and little accountability. Silicon Valley often criticizes Wall Street for its culture, and yet here we are. I want to be proud to work in tech, and this week I’m not.

Why social Darwinism is misguided

Snippet from a thoughtful essay by Patrick Bateson:

At the turn of the 20th century an exiled Russian aristocrat and anarchist, Peter Kropotkin, wrote a classic book called Mutual Aid. He complained that, in the widespread acceptance of Darwin’s ideas, heavy emphasis had been laid on the cleansing role of social conflict and far too little attention given to the remarkable examples of cooperation. Even now, biological knowledge of symbiosis, reciprocity and mutualism has not yet percolated extensively into public discussions of human social behaviour.

As things stand, the appeal to biology is not to the coherent body of scientific thought that does exist but to a confused myth. It is a travesty of Darwinism to suggest that all that matters in social life is conflict. One individual may be more likely to survive because it is better suited to making its way about its environment and not because it is fiercer than others. Individuals may survive better when they join forces with others. By their joint actions they can frequently do things that one individual cannot do. Consequently, those that team up are more likely to survive than those that do not. Above all, social cohesion may become a critical condition for the survival of the society.