The New York Times today runs an extraordinary article analysing how Washington Mutual, the largest failed bank in American history, went about lending money. The piece is based on interviews with two dozen former employees, mortgage brokers, real estate agents and appraisers and reveals the relentless pressure to churn out loans that produced the company’s meltdown. The reporters (Peter Goodman and Gretchen Morgenson) claim that their interviewees’ accounts are consistent with those of 89 other former employees who are confidential witnesses in a class action filed against WaMu in federal court in Seattle by former shareholders. The article is worth reading in full, but here are some of the juiciest quotes:

“We hope to do to this industry what Wal-Mart did to theirs, Starbucks did to theirs, Costco did to theirs and Lowe’s-Home Depot did to their industry. And I think if we’ve done our job, five years from now you’re not going to call us a bank.”

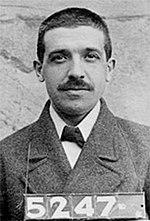

— Kerry K. Killinger, chief executive of Washington Mutual, 2003

“It was just disheartening,” said Sherri Zaback, a mortgage screener for Washington Mutual. “Just spit it out and get it done. That’s they wanted us to do. Garbage in, garbage out.”

As a supervisor at a Washington Mutual mortgage processing center, John D. Parsons was accustomed to seeing baby sitters claiming salaries worthy of college presidents, and schoolteachers with incomes rivaling stockbrokers’. He rarely questioned them. A real estate frenzy was under way and WaMu, as his bank was known, was all about saying yes.

Yet even by WaMu’s relaxed standards, one mortgage four years ago raised eyebrows. The borrower was claiming a six-figure income and an unusual profession: mariachi singer.

Mr. Parsons could not verify the singer’s income, so he had him photographed in front of his home dressed in his mariachi outfit. The photo went into a WaMu file. Approved.

WaMu gave mortgage brokers handsome commissions for selling the riskiest loans, which carried higher fees, bolstering profits and ultimately the compensation of the bank’s executives. WaMu pressured appraisers to provide inflated property values that made loans appear less risky, enabling Wall Street to bundle them more easily for sale to investors.

“It was the Wild West,” said Steven M. Knobel, a founder of an appraisal company, Mitchell, Maxwell & Jackson, that did business with WaMu until 2007. “If you were alive, they would give you a loan. Actually, I think if you were dead, they would still give you a loan.”

On the other end of the country, at WaMu’s San Diego processing office, Ms. Zaback’s job was to take loan applications from branches in Southern California and make sure they passed muster. Most of the loans she said she handled merely required borrowers to provide an address and Social Security number, and to state their income and assets.

She ran applications through WaMu’s computer system for approval. If she needed more information, she had to consult with a loan officer — which she described as an unpleasant experience. “They would be furious,” Ms. Zaback said. “They would put it on you, that they weren’t going to get paid if you stood in the way.”

On one loan application in 2005, a borrower identified himself as a gardener and listed his monthly income at $12,000, Ms. Zaback recalled. She could not verify his business license, so she took the file to her boss, Mr. Parsons.

He used the mariachi singer as inspiration: a photo of the borrower’s truck emblazoned with the name of his landscaping business went into the file. Approved.

On another occasion, Ms. Zaback asked a loan officer for verification of an applicant’s assets. The officer sent a letter from a bank showing a balance of about $150,000 in the borrower’s account, she recalled. But when Ms. Zaback called the bank to confirm, she was told the balance was only $5,000.

The loan officer yelled at her, Ms. Zaback recalled. “She said, ‘We don’t call the bank to verify.’ ” Ms. Zaback said she told Mr. Parsons that she no longer wanted to work with that loan officer, but he replied: “Too bad.”

Shortly thereafter, Mr. Parsons disappeared from the office. Ms. Zaback later learned of his arrest for burglary and drug possession.

The sheer workload at WaMu ensured that loan reviews were limited. Ms. Zaback’s office had 108 people, and several hundred new files a day. She was required to process at least 10 files daily.

“I’d typically spend a maximum of 35 minutes per file,” she said. “It was just disheartening. Just spit it out and get it done. That’s what they wanted us to do. Garbage in, and garbage out.”

By 2005, the word was out that WaMu would accept applications with a mere statement of the borrower’s income and assets — often with no documentation required — so long as credit scores were adequate, according to Ms. Zaback and other underwriters.

“We had a flier that said, ‘A thin file is a good file,’ ” recalled Michele Culbertson, a wholesale sales agent with WaMu.

Martine Lado, an agent in the Irvine, Calif., office, said she coached brokers to leave parts of applications blank to avoid prompting verification if the borrower’s job or income was sketchy.

“We were looking for people who understood how to do loans at WaMu,” Ms. Lado said.

Top producers became heroes. Craig Clark, called the “king of the option ARM” by colleagues, closed loans totaling about $1 billion in 2005, according to four of his former coworkers, a tally he amassed in part by challenging anyone who doubted him.

Christine Crocker, who managed WaMu’s wholesale underwriting division in Irvine, recalled one mortgage to an elderly couple from a broker on Mr. Clark’s team.

With a fixed income of about $3,200 a month, the couple needed a fixed-rate loan. But their broker earned a commission of three percentage points by arranging an option ARM for them, and did so by listing their income as $7,000 a month. Soon, their payment jumped from roughly $1,000 a month to about $3,000, causing them to fall behind.

I could go on, but you will get the point. One didn’t have to be a rocket scientist to know that this was madness. So how come the regulators didn’t spot it? And who is going to do a similar job on our own Northern Rock?