Like everyone else, I can remember exactly where I was when the attacks of 9/11 started. After watching the TV coverage for a while and it became clear that it was a terrorist attack, I wrote in my diary: “Today means the end of civil liberties for my lifetime”. In an interesting New York Review of Books piece David Cole is less pessimistic. But his tally of the aftermath and implications of the attacks is worth a read. Looking back, what’s most striking about the decade is how wasteful it has been in both resources and lives. The US (and the UK) got themselves enmeshed in one necessary war (Afghanistan), which they then screwed up by getting involved in an unnecessary one (Iraq). Air travel has been transformed from a convenience to an infuriating, inefficient nightmare. State surveillance has increased a thousandfold, and ‘security theatre’ has become a way of life not just for real security authorities but also for the millions of jobsworths who wear uniforms in corporate foyers. Every time I’ve queued at an airport in the last decade, or been told by a cop that I can’t take a photograph in a public place, my first thought is that bin Laden won hands down.

Like everyone else, I can remember exactly where I was when the attacks of 9/11 started. After watching the TV coverage for a while and it became clear that it was a terrorist attack, I wrote in my diary: “Today means the end of civil liberties for my lifetime”. In an interesting New York Review of Books piece David Cole is less pessimistic. But his tally of the aftermath and implications of the attacks is worth a read. Looking back, what’s most striking about the decade is how wasteful it has been in both resources and lives. The US (and the UK) got themselves enmeshed in one necessary war (Afghanistan), which they then screwed up by getting involved in an unnecessary one (Iraq). Air travel has been transformed from a convenience to an infuriating, inefficient nightmare. State surveillance has increased a thousandfold, and ‘security theatre’ has become a way of life not just for real security authorities but also for the millions of jobsworths who wear uniforms in corporate foyers. Every time I’ve queued at an airport in the last decade, or been told by a cop that I can’t take a photograph in a public place, my first thought is that bin Laden won hands down.

And just think of the cost of all this:

How much are we spending on counterterrorism efforts? According to Admiral (Ret.) Dennis Blair, who served as director of national intelligence under both Bush and Obama, the United States today spends about $80 billion a year, not including expenditures in Iraq and Afghanistan (which of course dwarf that sum).1 Generous estimates of the strength of al-Qaeda and its affiliates, Blair reports, put them at between three thousand and five thousand men. That means we are spending between $16 million and $27 million per year on each potential terrorist. As several administration officials have told me, one consequence is that in government meetings, the people representing security interests vastly outnumber those who might speak for protecting individual liberties. As a result, civil liberties will continue to be at risk for a long time to come.

Cole’s main point is that most of the heavy lifting in dragging the US government back to towards a law-abiding position was done by civil society groups and activists.

These developments suggest three conclusions. First, the values of the rule of law are more tenacious than many cynics and “realists” thought, certainly than many in the Bush administration imagined. The most powerful nation in the world was forced to retreat substantially on each of its lawless ventures.

Second, there is no evidence that the country is less safe now that the lawless measures have been rescinded. Bush administration defenders often assert that its initial responses were driven by necessity, but the fact that we remain reasonably secure under a more law-bounded regime refutes that claim. Indeed, even some of Bush’s own security experts now recognize that our success rests on resisting overreaction. Michael Leiter, head of the National Counterterrorism Center under Presidents Bush and Obama, maintained at the Aspen Security Forum in July that the way to defeat terrorism is “to maintain a cultural resilience,” and that if we do not overreact, “our basic principles that have held our country together…can continue to do so.”

Third, the choice to jettison legal constraints has inflicted long-lasting costs. The principal reason that we have yet to bring any of the September 11 conspirators to justice, ten years after their abominable crimes, is that we chose to “disappear” and torture them, thereby greatly compromising our ability to try them. And the decision to deny those at Guantánamo any of the most basic rights owed enemy detainees turned the prison there into a symbol of injustice and oppression, exactly the propaganda al-Qaeda needed to foster anti-Americanism and inspire new recruits and affiliates.

He finishes by quoting one of America’s greatest judges, Learned Hand, who once observed that

“Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can ever do much to help it. While it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.”

Yep.

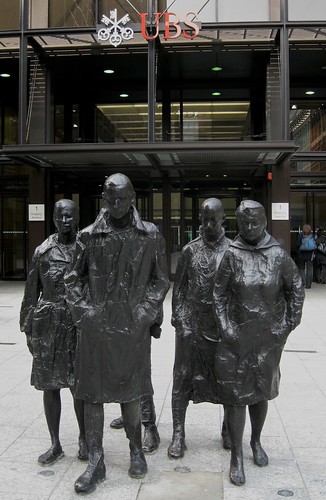

Oh, and btw, while we were diverted by the abovementioned security theatre, the world’s bankers were robbing us blind.

. Samples: